Analysis: Red faces follow Irish vote

- Story Highlights

- Ireland's no vote sends questions flying around the European Union

- Big plans in the Lisbon Treaty now appear on hold

- Ireland is the only one of 27 EU nations to ask its people to vote on the treaty

- Treaty would have created new powerful figureheads and streamlined bureaucracy

- Next Article in World »

LONDON, England (CNN) -- It is difficult to assess who is the most embarrassed by the Irish voters' rejection of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU's planned new constitution subtly re-packaged as a series of treaty amendments.

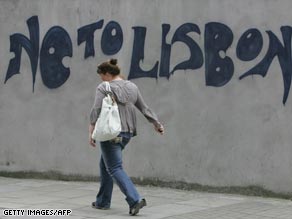

No campaigners get the message across on a Dublin, Ireland, wall.

Without ratification by all 27 countries the new constitution cannot go ahead.

Certainly it is a big blow for Brian Cowen, who has only just succeeded Bertie Ahern as Ireland's Taioseach and whose first significant test this was.

The new prime minister now has to attend his first EU summit on June 19-20 and explain to his EU counterparts how he has landed them in such a mess.

Plans for a new permanent President of the European Council and a new European Foreign Minister have to be put into cold storage. So are various efforts to streamline the EU machinery, with fewer votes subject to national vetoes, a new weighting system for qualified majority voting and the latest scheme for a slimmed down commission.

But Cowen is not the only one with a red face. The other major parties in Ireland backed the Yes campaign too. The referendum result amounts to a massive rejection of the whole Irish political establishment.

It is an embarrassment too to the other 26 leaders across Europe who, for fear of a similar outcome, have refused to stage popular votes and left the ratification process to more easily managed parliamentarians.

Critics of the constitutional treaty in their countries will now renew their 'we were robbed' protests, pointing out that in the only country where voters were allowed a say the people have rejected the institutional reforms. ![]() Watch how single-issue campaigners beat the establishment »

Watch how single-issue campaigners beat the establishment »

Don't Miss

Indeed, since the voters in France and the Netherlands in 2005 rejected the previous effort to provide the EU with a constitution the question arises whether any EU enterprise of this kind is capable of passing the test of a popular vote.

The Irish referendum result will be particularly sensitive in nearby Britain where Prime Minister Gordon Brown, whose party had originally promised a referendum on the old constitution, faces a court action over his refusal to stage one on the near identical treaty.

So where does the EU go from here? What is Plan B?

The difficulty in answering that is that the Lisbon Treaty was Plan B. Plan A was the constitution rejected by the French and the Dutch in 2005. And at present there is no trace of a Plan C.

Could the other 26 countries go ahead on their own, ignoring the Irish vote? No. That would be a complete contradiction of the spirit of the EU.

Could the Irish be invited to have another go? That is what happened when in 2001 they rejected constitutional changes set out at that time in the Nice Treaty. A year later, after a face-saving protocol or two making clear there was no threat to Irish military neutrality, the Irish voted again and this time, on a much higher turnout, backed the treaty.

The difficulty this time is that Cowen has ruled out a second vote and for the EU to push Dublin into another round of voting, after the French and Dutch were not asked to rethink in 2005, would look like an attempt to bully a small country.

That leaves two other possibilities: limping on permanently with the Nice Treaty, designed for a much smaller EU, or going back to the drawing board and starting again. And that last option is one which fills all concerned with dismay.

Not only is the process of constitution-mongering a fractious, divisive and frankly boring exercise, it is one which alienates European citizens from the EU and all its works. They want their politicians to be tackling problems like immigration, energy security and employment, not tinkering endlessly with their institutions.

Some of the roughest words in advance of the Irish vote came from the French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner when he said: "It would be very, very troubling that we would not be able to count on the Irish, who counted a lot on Europe's money. The Irish would truly penalize themselves."

Such an implied threat almost certainly proved counter-productive. But it also reflected the frustration that Kouchner and his President Nicholas Sarkozy will feel now.

On July 1 France takes over the six month revolving presidency of the EU. Sarkozy, true to form, is buzzing with big plans to make Europe politically vital again, promising a big initiative on immigration, a revitalized European defense dimension and a bid to harmonize business taxes (in itself one of the factors in the Irish vote since Ireland has benefited hugely from undercutting others with its low business taxes).

Now Sarkozy , one of the main drivers behind the Lisbon Treaty will have to take time out going back to the same old constitutional questions. Not his idea of fun. Or anybody's.

Sit tight, we're getting to the good stuff

Sit tight, we're getting to the good stuff