Story highlights

CNN travels with the Libyan national soccer team to Zambia

The team's campaign to qualify for the Africa Cup of Nations coincided with Libya's civil war

Several of the players had fought on the front line for the rebels

The Africa Cup of Nations is one of the biggest tournaments in world football

It’s 10 minutes after the final whistle has blown but still no one knows whether their efforts have been in vain.

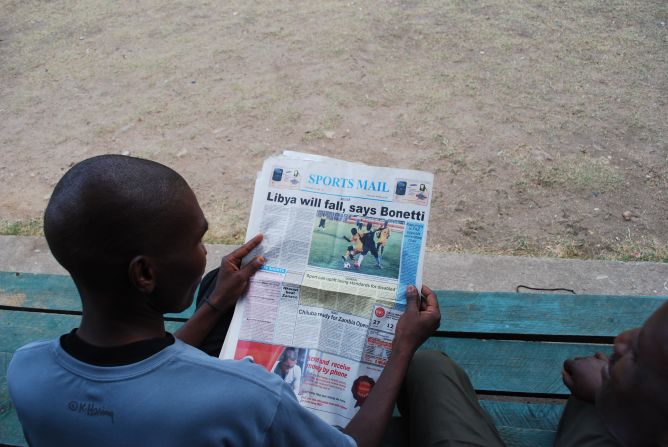

The Libyan national soccer team sit in the dressing room at the Nchanga Stadium – in Chingola, a small copper mining town on the Zambia-Congo border – quietly waiting for news amidst the fog of sweat and redolence of rubefacient muscle rub.

The team has just drawn 0-0 with Zambia in their final qualification match for the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations, a qualification campaign that began with the country under the rule of Colonel Moammar Gadhafi, continued through the civil war and ended before the death of the former notorious leader.

Victory was needed to be sure of progression to next January’s tournament in Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. A draw meant that results elsewhere had to go their way.

As their campaign for Africa’s biennial continental championship progressed with war as the backdrop, some players declared the team was behind Gadhafi. Others left the team to go and fight on the front line with the rebels.

In unison, somehow, they qualified; news that will shortly be relayed to the team when confirmation of results from other matches are circulated.

Six days earlier coach Marcos Paqueta is in good spirits in the lobby of his hotel in Tunis. The security situation is such that the team could not train in Tripoli. The Brazilian coach once famously won the under 17s and under 20s World Cups in the same year for his homeland, but signed for Libya in June 2010 when the Libyan Football Federation was run by one of Gadhafi’s sons, Mohamed.

“When I was there the first time I contacted only the federation, then one time I have one meeting with Dr Mohamed,” Paqueta explains of his dealings with the Gadhafi regime.

“He was happy because of the project I made for the national team and Libyan football. I focus only on sports. At that time you don’t know about the country.”

In the past, the Gadhafi family’s dealings with soccer and its players had been much more hands on. His son Saadi played for Al Ahly Tripoli and installed himself as captain of the national team. The team plummeted to 186th on FIFA’s rankings.

But they also used soccer as a political tool. In 2000 Saadi’s Al Ahly Tripoli traveled to Al Ahly Benghazi for a league match. Benghazi had long been associated with Libya’s opposition and the team’s fans paraded a donkey wearing Saadi’s shirt.

“It is a bad story, not a funny story,” says 29-year-old defensive midfielder Moataz Ben Amer, the current captain of Al Ahly Benghazi.

“The first half, Tripoli are winning. But the referee is no good. So Ahly Benghazi goes to the airport [in protest]. Saadi Gadhafi turned up with his dogs and the police and said: ‘If you don’t play the second half, we will kick you’.”

Unsurprisingly, the players returned to play the second half, and lost 3-0.

Colonel Gadhafi was so incensed that he ordered Al Ahly Benghazi’s training ground to be destroyed. The club was also banned from domestic competition for five years. When Interpol released a “Red Notice” for Saadi Gadhafi in September, the allegations given were “misappropriating properties through force and armed intimidation when he headed the Libyan Football Federation.”

Paqueta’s early results were encouraging. Libya beat Zambia, one of Africa’s best teams, in Tripoli. But then in February civil war broke out, dividing the players. After Libya had beaten the Comoros Islands in March the team’s former captain, 34-year-old Tariq Taib, declared that the players were 100 per cent behind Gadhafi. He even labeled the rebels “rats and dogs.”

Walid el Kahatroushi disagreed. The 27-year-old midfielder scored in that game but when the team gathered again in June, he decided to leave the camp and fight for the rebels when he heard a friend had been injured in the violence.

“Some people come to me and told me one of my dear friends was in the hospital and lost his arm … in that moment I decided to leave the camp and join the front line … in Jebel Nafousa,” explains Kahatroushi.

Life on the front line was hard. Friends would shield him from worst of the fighting until, in the end, he felt he had no choice

“When I was there I was just about forgetting about football because the most important thing then is how to secure your life and secure the life of your friends. If it was about me I would never come back, you would never find me here playing football. But … my friends on the front line told me: ‘This is your future, you must go there. This is also like a war for you’.”

Others left for the front line too, like goalkeeper Guma Mousa, but not all were so lucky. Ahmed Alsagir was shot in the shoulder and spent a month in hospital before returning to the front line. By the end of August Gadhafi had been toppled. A week later the team had to play their penultimate qualifier against Mozambique behind closed doors in Egypt.

Aside from the trouble of getting the players out of the country, there were some more practical concerns. For one, Paqueta had to hold a clear the air meeting with the squad. The old pro-Gaddafi players were nowhere to be seen. A new kit had to be designed, with the rebel’s flag stitched on to it. The Libyans fought out a 0-0 draw.

“The last game [against] Mozambique, it had a big impact on the people in Libya. Everyone was happy and everyone was talking about us,” recalls Kahatroushi.

“We will do everything to qualify, Inshallah, because this will help our country too much. At least to bring them some happiness after all the sadness they have been through.”

The journey south to Zambia took almost 24 hours, but the players are ready when they take to the pitch at the packed Nchanga Stadium. Libya’s new captain, 39-year-old goalkeeper Samir Abod is the hero, making three world class saves. The match finishes 0-0. Some of the players collapse on the floor in tears. Others pray before returning to the dressing room.

They wait.

The quiet is broken when one of the coaches bursts in and breathlessly delivers the news. The blue-painted room erupts in celebration and song. The rebel national anthem is sung as the new flag is held aloft in the center of the melee.

Ghana’s victory and a last-minute equalizer for Guinea against Nigeria means that Libya has, against the odds, qualified for the Nations Cup. As a nation recovers thousands of miles away from the ravages of civil war under the new interim government, Walid Kahatroushi leads the celebrations and the chants.

“The blood of the dead,” they sing, “will not be spilt in vain.”