Uncovering the hidden archives of the civil rights movement

- Participants kept artifacts because mainstream museums weren't interested

- Cost can be problematic: Rosa Parks bus went for $492,000, pair of slave shoes for $29,000

- Smithsonian director: Small items, such as glass shards from bombing, help tell story

- Oral histories integral part of story because "there's nothing like the first voice"

Hero or traitor? Ernest Withers' lens captured pivotal moments in civil rights history. Now, FBI documents expose a darker angle. Soledad O'Brien investigates in "Pictures Don't Lie," an In America special, at 8 p.m. ET Feb. 26.

(CNN) -- The hard-won fight for civil rights could go down as one of the most thoroughly archived periods in American history, largely because participants kept photos and objects that would later tell their stories.

The revolution demanded it, even if the keepers of history at the time didn't.

At the height of the movement, there was no market for historic African-American artifacts. Mainstream museums weren't interested in documenting it, and "if you look at how museums and scholars had interpreted African-American history up until the '60s, it had been very biased and one-sided," said John Fleming, director of the International African-American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina.

"The civil rights movement itself sparked a consciousness on the part of black people that they needed to preserve their documents and culture."

Important items were tucked away and began to surface in the 1970s and 1980s. A handful of African-American museums blossomed to more than 100 by the early 1990s. Today, the Association of African American Museums boasts 250 members.

"Communities wanted to be in control of their own history, culture and artifacts. They wanted to be the interpreters of that history and culture," said Fleming, who also was executive producer of "America I Am," a traveling 12,000-square-foot exhibition highlighting African-American achievements.

Still, putting together a collection isn't easy.

Unwritten history, uncovered

Not only can the cost and elusiveness of artifacts be prohibitive, but problems can also arise when the history being documented isn't fully written yet.

"It does pose a challenge -- there's no question about that -- because all of this is still a work in progress," said David Simmons, curator and director of the Ernest Withers Collection Museum and Gallery in Memphis, Tennessee.

Simmons, who was tapped in October to sort through Withers' million-image catalog, speaks from experience.

A month before Simmons' appointment, newspaper reports outed the iconic civil rights photographer as an FBI informant. There were ugly implications that Withers had jeopardized the civil rights movement through his cooperation with the feds. Simmons, who had forged a friendship with Withers well before his 2007 death, stood by him.

Read why an old friend doesn't consider Withers a traitor

The controversy will serve only to stoke interest in the collection, Simmons hopes, but he has already seen some backlash, including a corporate sponsor that "put funding on hold pending resolution to the FBI issue."

Money can pose obstacles to any archiving endeavor, especially for smaller museums, said Beverly Robertson, who presides over one of the nation's most famous African-American museums: the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, the site of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination.

"Most museums like ours don't have deep enough pockets for artifact acquisition," she said.

Museums and centers receive donations, but some artifacts command hefty sums.

When the aging, battered bus on which Rosa Parks refused to relinquish her seat went to auction in 2001, the Henry Ford Museum paid $492,000 for it. Fleming said he once found a pair of shoes that had been worn by a slave. The asking price? $29,000.

"That's how rare these things are," Fleming said.

Digging for memories

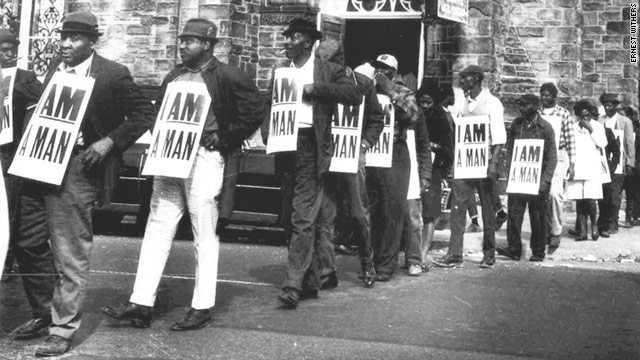

Some artifacts are easier to obtain; you just have to ask the right person. Robertson recalled speaking to a Memphis resident about her museum's troubles finding an "I Am A Man" poster from the 1968 sanitation workers' strike that fatefully brought King to Tennessee.

To her surprise and delight, the man replied, "My dad has three of them, and if the museum wants to display them, I'll bring them down right now."

Gallery: Ernest Withers

Gallery: Ernest Withers

Entrenched in civil rights fight

Entrenched in civil rights fight

Jim Crow era travel guide

Jim Crow era travel guide

The 'girl in the stroller' looks back

The 'girl in the stroller' looks back

Robertson and other museum directors said there are plenty of items still to be uncovered. There are troves of relics gathering dust in grandparents' basements or attics, and other items remain in the personal collections of civil rights luminaries such as Rep. John Lewis, the Rev. Joseph Lowery or former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young.

"They're scattered everywhere, and you really have to dig deep," she said. "I think sometimes the families don't know what they really have. They might not know the treasure that they sit on."

Historic value comes in a variety of forms: shackles worn by a slave, pieces of glass from the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing, a Ku Klux Klan uniform, a key to King's Birmingham, Alabama, jail cell or a writing desk used by poet Phillis Wheatley.

There also are items like Withers' 1955 images of the Emmett Till trial or video of the violent police reaction to the 1965 Selma march, both credited with sparking global awareness of the plight of blacks in the South.

Watch how Withers obtained his amazing access

Sometimes, everyday objects -- a quilt or piece of paper -- are just as important. One of the prized components of the "America I Am" exhibit is a 1776 bill of sale for a black woman and child, Fleming said.

An artifact is a "tangible manifestation of the past," said Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African-American History and Culture, slated to open in Washington in 2015.

Though items are important for different reasons, they all play roles in telling the story, he said.

"While the story, the interview of living people is crucial to understanding it, there is something powerful about people seeing the actual object," he said. "Things stimulate our memory."

Talk and technology

Oral histories remain important, too. The Smithsonian has a partnership with StoryCorps to make sure first-person accounts are included in its collection.

Several groups have undertaken similar initiatives, including AARP, "America I Am," the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and The HistoryMakers out of Chicago.

--Lonnie Bunch, founding director, Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture

Julieanna Richardson, founder of The HistoryMakers, said she was inspired by slave narratives, a collection of 2,300 first-person slavery accounts commissioned as part of the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. She called the idea brilliant for its time but said the written accounts surely imparted the writers' biases.

The HistoryMakers hopes to erase any subjectivity by letting the interviewees -- which include doctors, musicians, athletes, entrepreneurs and politicians -- have their stories videotaped during a span of three hours. It's not exclusive to the civil right movement: The youngest subject was 29, the eldest, 113.

"There's nothing like the first [person] voice, nothing," Richardson said. "You can see the twinkle in someone's eyes. You can see their reflection. You can see when they're pensive."

It's fitting that photography and videos -- the same technology that sent out the clarion call for equality -- are integral to retelling the stories of civil rights soldiers today. Several museum directors say technology is also key to expanding on the narrative.

Watch a sneak peek of CNN's documentary, "Pictures Don't Lie" ![]()

Whether it's databases, educational portals or the Smithsonian's mission to make its collection as accessible as possible, technology will only assist in archiving the movement.

"Using technology, we can get into the reservoir of change and possibility that was the civil rights movement," Bunch said. "I think we will begin to understand the variety of mechanisms and variety of sources that were the civil rights movement."