Lea este artículo en español/Read this article in Spanish

Story highlights

NEW: "Reports of my survival may be exaggerated," Colvin wrote hours before her death

At least five journalists have now been killed in Syria this year

Colleagues remember longtime reporter Marie Colvin as "a class act"

Prize-winning French photographer Remi Ochlik, 28, also dies in shelling

The deaths of two Western journalists Wednesday in Syria – where at least three other journalists have been killed in covering the uprising – highlight the danger reporters face in covering conflict zones.

Marie Colvin, a longtime American foreign correspondent for London’s The Sunday Times, and prize-winning war photographer Remi Ochlik, 28, were killed in shelling in the city of Homs, the besieged center of resistance to President Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Colleagues remembered Colvin, 56, who lost her left eye to shrapnel while covering a conflict in Sri Lanka, as “a legend” and “a class act.”

Ochlik had covered conflicts from Haiti to Libya, and he won first prize in the 2011 World Press Photo general news category for a photograph of a rebel fighter resting in front of a rebel flag in the war-torn landscape of Libya’s Ras Lanuf.

The French Foreign Ministry demanded that Syria give the International Committee of the Red Cross access to Homs to remove the journalists’ bodies.

“This shows how much the freedom to inform is important, how the work of a journalist can be so difficult,” French President Nicolas Sarkozy said Wednesday. “I want to pay tribute to them because if reporters were not over there, we would not know what is going on.”

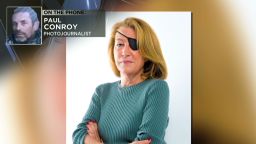

At least one other journalist, photographer Paul Conroy, was wounded in the attack, The Sunday Times said, adding that initial reports suggest his wounds are not serious.

The two journalists’ deaths come less than a week after New York Times reporter Anthony Shadid, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, died in Syria apparently of an asthma attack.

Colvin’s legacy is to “live a passionate and important life as you see it,” her mother, Rosemarie, told CNN. “Do what you’re committed to, to the highest level you can do it – because that’s what she always did. Overcome the obstacles that you meet as best you can.”

Rosemarie Colvin said she never told her daughter to stop doing her work because “it was the most useless conversation you could have had. … From the time she was a little child, she was committed to doing things that were important.”

“She was a ferocious correspondent, and ferociously funny,” said CNN’s Jim Clancy. “I just loved spending hours with her talking about the people, the places and the stories.”

The emergencies director for Human Rights Watch, Peter Bouckaert, called Colvin “a legend among her fellows. She was always the first one to show up – long before anybody else would arrive, and she really had a passion to report from these difficult places.”

Bouckaert said Colvin had contacted him Tuesday about a story she had written for The Sunday Times, which requires readers to pay before gaining access to the website. “She said, ‘Please, put my story … over the pay wall, and I will face the firing squad tomorrow at the paper. I don’t often do this, but it is sickening what is happening here.’

“So, we posted the story on a private Facebook page for journalists, and another journalist commented that he was relieved that she had already left Homs. So her response, her last message to us, said, ‘I think the reports of my survival may be exaggerated. I’m in Baba Amr. It’s sickening trying to understand how the world can stand by and I should be hardened by now. I watched a baby die today. Shrapnel. The doctors could do nothing. His little tummy just heaved and heaved until it stopped. I’m feeling helpless as well as cold. I will try to keep getting out the information.”

Rupert Murdoch, the media magnate who owns The Sunday Times, said Marie Colvin “put her life in danger on many occasions because she was driven by a determination that the misdeeds of tyrants and the suffering of the victims did not go unreported.”

And John Witherow, the editor of the paper where she worked for more than 25 years, said Colvin “was much more than a war reporter. She was a woman with a tremendous joie de vivre, full of humor and mischief and surrounded by a large circle of friends.”

See Remi Ochlik’s award-winning photos here

Colvin spoke to CNN about the suffering in Homs the day before she died.

She told Anderson Cooper that Syria was the worst conflict she had covered, partly because of the sheer amount of ordnance falling on Homs.

“There’s a lot of snipers on the high buildings surrounding the neighborhood. I can sort of figure out where a sniper is, but you can’t figure out where a shell is going to land,” she said.

Colvin had reported from many conflicts, including last year’s Libyan civil war, where she saw the shelling of the rebel port city of Misrata.

She stayed in the city after many of her colleagues had left, she told the Public Radio International program “The World” in May.

“It is very dangerous, I mean, it has to be said, and I think part of that danger is also the expectation of shelling. I mean, it’s very random,” she said.

At 20, Ochlik started photographing conflicts, first in Haiti, and then he went on to cover the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the presidential elections in Haiti in 2010, and the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, his website says.

His work was published by Le Monde Magazine, VSD, Paris Match, Time magazine and The Wall Street Journal.

At least three other journalists have been killed in Syria’s nearly year-old conflict. France 2 TV journalist Gilles Jacquier was killed on January 11 when a mortar shell struck a pro-government rally he was attending as part of a government-authorized tour of Homs, his network said.

Syrian journalists Shukri Abu al-Burghul and Mazhar Tayyara were also killed.

Before the deaths of Colvin and Ochlik, the Committee to Protect Journalists said that at least 11 journalists have already been killed around the world this year.

CNN’s Hala Gorani, who reported from Syria last summer on a government-sanctioned trip, later wrote about the dangers journalists faced.

“Away from the prying eyes of government minders, they risk imprisonment, torture, even death to cover the rebels,” she said.

Why do some journalists decide to risk so much by reporting from dangerous locations such as Syria?

These journalists are “out there doing their job not for the glory, not for the recognition, but because they genuinely believe that truth is valuable and will ultimately end suffering that otherwise would happen in the darkness,” said Al Tompkins, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute, a leading journalism school.

“These are places where we need journalists to be,” Tompkins told CNN. “They are there as our surrogates, because without their firsthand information we have only the partisan government reports to rely on. We know the cost of unreliable government information.”

Currently, CNN and other media outlets often cannot independently verify opposition or government reports because the Syrian regime has severely limited access to the country by foreign journalists.

“We know that the cost of sending journalists into harm’s way can be high,” Tompkins said. But “the cost of not going there is even higher.”

With daily reports of civilian fatalities in Syria, some critics may question the amount of attention focused on the deaths of a couple of Western journalists. But these deaths may resonate more with readers in places such as the United States, said Kelly McBride, another senior faculty member at Poynter.

“In these distant, remote conflicts, it’s so hard to know what’s really going on,” McBride said. “People actually appreciate the valor of independent journalists who do this work. … That’s why people are so upset.”

Tompkins noted that “in any story when you can attach a recognizable name and face to a story, the story becomes more relatable.”

“This would be a day where it would be right for readers, viewers, and listeners to just to take a moment and thank the brave men and women who go to the world’s hellholes on their behalf, to find out what’s going and bravely report it,” Tompkins said.

CNN”s Niki Cook in Paris, Ronni Berke in New York, and Alan Silverleib in Washington contributed to this report