Story highlights

NEW: Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi leads with most results in

Ahmed Shafik, a Mubarak ally, is running a close second, according to local media reports

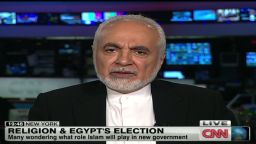

Morsi and Shafik are highly polarizing candidates for many Egyptians, an analyst says

The final results of the first round of elections are due Tuesday

Egypt’s landmark presidential election looks set to go to a run-off vote in which Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi could face former regime figure Ahmed Shafik, according to partial results reported Friday.

Ballots are still being counted, and the final results of the first round are due Tuesday.

Egyptian newspaper Al Ahram Online gave Morsi 26.48% of the vote with results in from 25 of 27 provinces, with Shafik, who was ousted President Hosni Mubarak’s last prime minister, close behind with 24.74% of the vote and leftist Hamdeen Sabahy in third with about 20%.

The partial results put Abdelmonen Abol Fotoh, a moderate Islamist running as an independent, and Amre Moussa, who previously served as foreign minister and headed the Arab League, in fourth and fifth places, respectively, Al Ahram Online reported.

Results are still to come from the Cairo and Giza provinces, which could prove decisive for the first round of voting, the newspaper said.

The Muslim Brotherhood earlier told reporters that with about 90% of the vote counted, Morsi – who heads its political wing, the Freedom and Justice party – was in the lead, with Shafik in second place.

If no candidate gets a majority of the vote in the first round, the top two will progress to a run-off to be held June 16-17. There were 13 candidates on the ballot, although two withdrew from the race after ballots were printed.

Whoever wins the historic vote will become Egypt’s first freely elected president.

But if the first round results in a run-off between Morsi and Shafik, many Egyptians – particularly liberals and “revolutionaries” – will be very disappointed, said Khaled Elgindy, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington who is currently in Egypt.

“A lot of Egyptians will feel like this is the worst choice that they would have to make because if it really is between Morsi and Shafik, then these are the two most polarizing candidates,” he said.

Many people may opt to stay at home rather than make a “very difficult choice” in the run-off, Elgindy said.

It is hard to predict where the votes of liberals and revolutionaries will go if they do participate, but the Muslim Brotherhood will have to work hard if it wants to win them over, having alienated many in the past, he said.

There is also a chance of further protests and even violence, regardless of who wins, Elgindy said, as revolutionary elements become increasingly marginalized and radicalized.

“There is a likelihood of a ‘revolution part 2,’ and there is also a growing likelihood of violence,” he said. “There are elements that are itching for confrontation on the streets because that’s where they feel they are strong.”

Elgindy believes the biggest winner could be the country’s current military leadership, which has still to detail the powers of the presidency and may see the election of an ally in Shafik. If Morsi were to win, the military leadership would be likely to constrain the powers of the president, he said – and in any case is likely to keep control of key areas such as defense and foreign policy.

The early results don’t appear to suggest a surge in support for the Islamists, despite Morsi edging ahead, Elgindy said.

Together, the two main Islamist candidates – Morsi and Abol Fotoh – seem to have taken about 40% of the vote, he said, a significant drop in share from the 70% of seats won in parliamentary elections in January by Freedom and Justice and another Islamist party.

This fits with a trend in the last six months against the Islamist factions and toward stability, Elgindy said.

“This has worked to the advantage of someone like Shafik who can capitalize on the fact that people are worried, are becoming more fearful about the security situation. (There is) also a lot of fear-mongering about the Islamists,” he said.

“People are disaffected with the Islamists because they saw they had a couple of months in parliament and didn’t do much – and there’s a growing sense that maybe they are trying to hijack the revolution and take over.”

That said, the apparent success of Morsi and Shafik is not a surprise in that they come from the two most organized, best resourced camps in the election, he said: the Brotherhood and the remnants of the old regime.

Morsi is an American-educated engineer who vows to stand for democracy, women’s rights and peaceful relations with Israel if he wins the Egyptian presidency. He’s also an Islamist figure who has argued for barring women from the Egyptian presidency and called Israeli leaders “vampires” and “killers.”

The Muslim Brotherhood had originally pledged not to seek the presidency.

Shafik, a former air force officer with close ties to Egypt’s powerful military, is seen as representing the interests of the old guard – those who lost out when President Mubarak was ousted.

Mubarak led the North African nation for 30 years before being forced out last year amid a popular outcry.

He is awaiting a court’s verdict and could potentially face the death penalty after going on trial for corruption and allegedly ordering the killing of anti-government protesters.

About half all Egypt’s roughly 50 million registered voters had cast ballots by the end of Thursday, the second and final day in the nation’s historic presidential election, said Farouk Sultan, head of the Higher Presidential Committee.

Amid worries by some that Egypt’s current military rulers might somehow hijack the election, Sultan detailed the vote counting process – including checks and balances aimed at ensuring credibility.

According to the committee head, votes will be tallied in the various polling locales by a judge and in the presence of representatives of the candidates. Each final count will be announced aloud, then an official report will be filed that can be viewed by nonprofit groups, the media and candidates, Sultan said.

The voting is a monumental achievement for those who worked to topple Mubarak in one of the seminal developments of the Arab Spring more than a year ago. And it could reverberate far beyond the country’s borders, since Egypt is in many ways the center of gravity of the Arab world.

Distrust and anger in Egypt, particularly against the military’s power in governmental affairs, have inspired continued protests, some of which have been marked by deadly clashes.

Many protesters are upset about what they see as the slow pace of reform since Mubarak’s ouster. Some are also concerned that the country’s military leadership is delaying the transition to civilian rule.

Worries about the powerful military possibly swaying this week’s vote persist despite the insistence of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces that it will hand over power to an elected civilian government.

The military leaders put armored personnel carriers on the streets with loudspeakers broadcasting a message that they will relinquish power, but that did not convince doubters.

In January, two Islamist parties – the Freedom and Justice Party with 235 seats and the conservative Al Nour party with 121 seats – won about 70% of the seats in the lower house of parliament in the first elections for an elected governing body in the post-Mubarak era. The rest of the assembly’s 498 seats were divided among other parties.

Journalist Mohamed Fadel Fahmy reported from Cairo, and CNN’s Laura Smith-Spark from London and Salma Abdelaziz from Atlanta.