Story highlights

CNN correspondent joins scientists on mission to Greenland to understand how the vast ice sheet is changing

Aerial radar missions and ice core drilling data helping build picture of past climate and helps predict future

Melt layers point to extremely warm summers here in the recent years, according to scientists

"We are doing an experiment with our planet and we have no idea what the outcome will be," says glaciologist

For hundreds of years the Arctic has fascinated explorers and scientists who wonder what treasures may lie under the massive ice plains that occupy much of the territory here.

Adventurers from across the globe have been coming to Greenland for years to try and uncover what secrets lay beneath the massive ice shield here, which is more than twice the size of the U.S. state of Texas. It turns out that many of the riches are not hidden under the frozen and compressed snow layers, but right in them.

Scientists gather a wealth of information from the ice in Greenland. It gives of them details on climates dating back more than 100,000 years, including temperatures, precipitation, cloud cover, and special occurrences such as volcanic eruptions that leave traces of ash.

“If we can understand the past, then it will help us better predict the future of climate change,” says Trevor Popp, a climatologist from the University of Copenhagen.

“And Greenland is the best place to experience the processes first hand. Someone once told me this is where the rubber meets the road when it comes to studying climate change.”

Read: Chasing down the world’s vanishing glaciers

An abundance of research missions have been launched to the Arctic ice shield. One of the most respected organizations working here is Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research.

The AWI as it is known as has now given CNN the chance to participate in a mission to the Arctic, featuring the institute’s most advanced new research aircraft, Polar 6.

“It is a two-fold mission,” Daniel Steinhage the geophysicist who headed the endeavor told us. “On the one hand we will fly radar survey missions over the ice to penetrate the first hundred to two hundred meters. Then we will land in some of the places along our flight route to drill shallow ice cores for more exact results.”

The mission’s goal was to develop an improved method to map the upper layers of Greenland’s Arctic ice, down to about 150 meters under the surface, in a bid to improve climate projection models that try to tell us how temperatures, rainfall and weather patterns on earth will evolve in the future.

The research seems urgent after increases in severe weather like hurricanes have increasingly raised the question of how global ice melt contributes to these weather phenomena.

Read: Greenland, Antarctica ice melt speeding up

Sepp Kippstuhl, a glaciologist at AWI says researchers are not sure how much humans contribute to climate change, but that industrialization and the emissions it creates surely have effects on climate.

“We turn on so many screws that something somewhere has to change, but we don’t know what that change is or how severe it is. That is why we are trying to improve our climate modeling,” says Kippstuhl.

The AWI’s mission to the Arctic will try and improve methods of gaining data on ice melt in the Arctic. After outfitting the Polar 6 research aircraft with antennas and state of the art computer systems for over a week, the team and the aircraft head to Kangerlussuaq in Greenland – a former U.S. military base that is home to about 600 people and the largest airfield on the island.

Polar 6 is a unique plane. The airframe comes from a DC-3 Dakota, a plane used by the U.S. and other militaries in World War II and the following years to transport goods. However, while Polar 6 might look like an old plane, it is outfitted with state of the art modern avionics and brand new engines, making it as reliable as any modern day aircraft.

Read: Greenhouse gases reach new peak

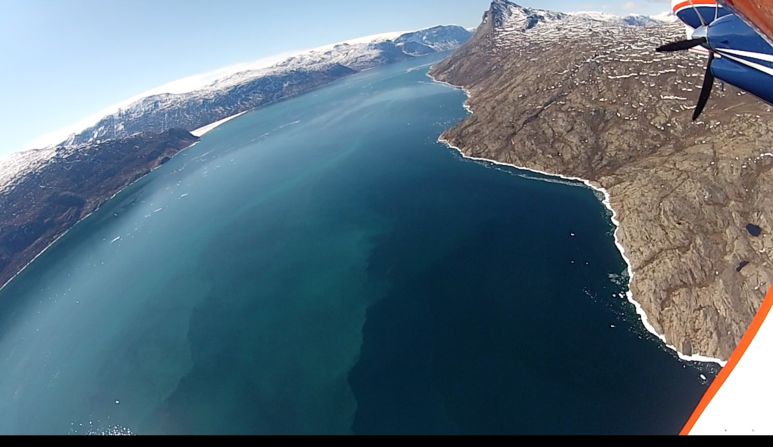

The first part of the AWI’s polar mission was conducting radar survey flights to the middle of Greenland’s ice shield. After take off from Kangerlussuaq and a flight over some of the most majestic fjords in the world, Polar 6 reached the glaciers on the fringes of Greenland’s inland ice. It took the aircraft another two hours to get to the radar survey area.

The ice here is a lot like the salt flats in Nevada, there are no hills or valley, no landmarks whatsoever, making it extremely hard for the pilots to distinguish the clouds from the surface.

“The extremes that we operate in are really not something that can be taught,” Polar 6’s captain Erik Bengtsson, a Canadian, told us while navigating the ice plains.

“You need to just gain experience flying in these conditions and you always have to keep an eye on the weather because it changes so quickly out here.”

Around three hours into our flight, Steinhage was finally able to boot his computers and start using the radar equipment.

Read: Trying to agree a Kyoto 2.0, as the planet simmers

“The radar penetrates about 150 to 200 meters into the ice,” Steinhage said, while monitoring a variety of screens in the plane’s hull. “The useful data goes about 100 to 120 meters deep, after that it is very distorted, but the data from those depths is very useful.”

The data gathered by Polar 6’s radars is part of the puzzle to try and map conditions in the top layers of the arctic ice shield. The ice here consists of compressed snow that fell in Greenland in the past and was then pressed into layers as more and more precipitation came down over the years. The ice is layered much like tree rings. Each layer represents a certain point in time and gives clues to the climate conditions of that era.

“If we can understand the past and get data from the past, then we can enter that information into our computers and run it forward to try and predict how the climate will change in the future,” Steinhage said.

“The problem we have is that every time we get new data there are also new questions as well. There are so many factors influencing the world’s climate that it is very hard to predict how it will change in the future.”

But each bit of information also delivers some answers to questions about the how our climate is evolving.

Read: Drought-stressed trees face race to adapt

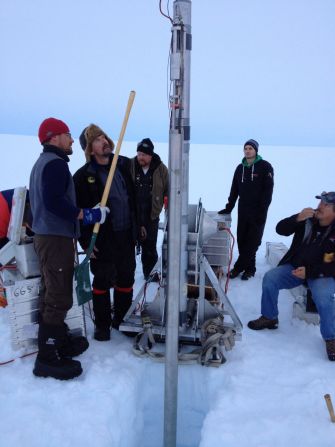

For the second part of the AWI’s missions, the team loaded a heavy drill into Polar 6’s hull and landed right in the middle of the ice shield on skis to drill ice cores.

Delivering the drill with a plane is unique in itself, so far researchers would mostly use snow mobiles or other special vehicles to transport equipment to drill sites. A process that could take days, with Polar 6 only takes a few hours.

Sepp Kipfstuhl is in charge of shallow ice core drilling at the AWI and brings more than 30 years of experience to the table. After a rough landing right on Greenland’s inland ice, Kipfstuhl and his team set up their drill and begin working.

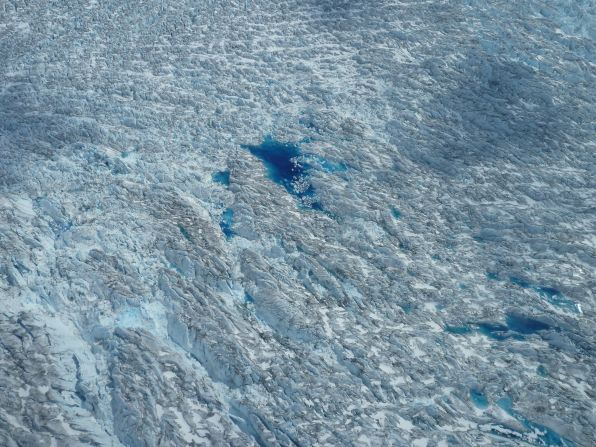

The cores they pull out of the ice will have to be scientifically evaluated in a lab for months after the end of the mission, but with his experience Kipfstuhl immediately points to signs that point to very warm summers here in the Arctic in the past years.

“On the ice you will see melt layers,” he says pointing to dark and very compressed layering in the ice. “They are extremely prominent melt layers and guys who drilled here 30 years ago say they don’t remember melt layers this prominent. The melt layers point to extremely warm summers here in the past years, where the ice surface melted and then froze again during the winter.”

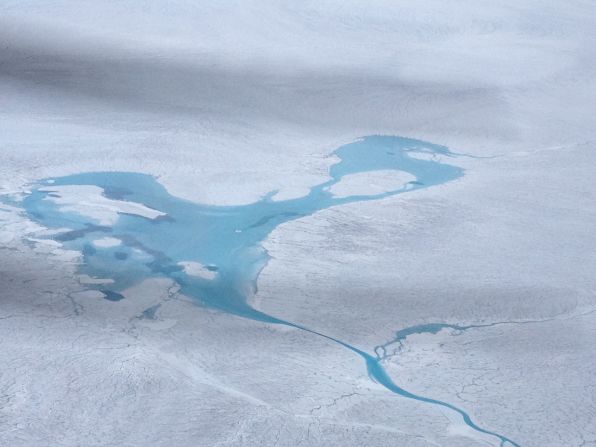

That preliminary evaluation is also backed by NASA data from its ice tracking satellite. The space agency recorded unprecedented surface ice melt in the Arctic this past summer with about 97% of Greenland’s inland ice showing signs of thawing. In normal years, about 50% of the ice shield’s thaws. This process is also clearly visible from the air as Polar 6 flies over Greenland. Clear blue meltwater ponds dot the landscape, growing larger under the Arctic summer’s sun.

Kipfstuhl and his team spent about seven hours drilling on the ice shield. All of the work happens at night because during the day the thawing is so bad that the ice surface becomes too slushy to operate a drill – another sign that temperatures are rising.

Like most scientists, Kipfstuhl is not willing to speculate how much humans are contributing to global warming. But he does say that humanity is taking a big risk.

“We are doing an experiment with our planet and we have no idea what the outcome will be, what the result will be. All we can do is try to predict it, but there are so many variables in our environment that it is very hard,” he said.

The debate on climate change is extremely politically charged and it is hard to get unbiased information. In a nutshell climate researchers will give the following facts.

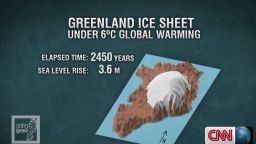

The earth is getting warmer. Temperatures have increased dramatically since the industrial revolution but it is still unclear how much humans are contributing to global warming because there have been warmer and colder climate cycles in the past. Warming temperatures and ice melt will lead to rising sea levels and may be contributing to more frequent and more intense severe weather on earth.

There is very little certainty in today’s climate research and missions like the one that the Alfred-Wegener-Institute conducted in Greenland constantly try to improve the available data to give a more accurate picture of what the future might hold on this planet we inhabit. Their predictions become a little more accurate with every expedition but every mission also brings up new sets of questions that will take decades to answer.