Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter: @FridaGColumns.

Story highlights

Frida Ghitis: Democracy proving hard because Egyptians seems not to grasp how it works

She says many, particularly those who gain power, believe it is about imposing will on losers

She says Morsy, Brotherhood pushing Islamist style power, their constitution an affront

Ghitis: Opposition has uphill battle to make case. Egypt risks losing "consitutional moment"

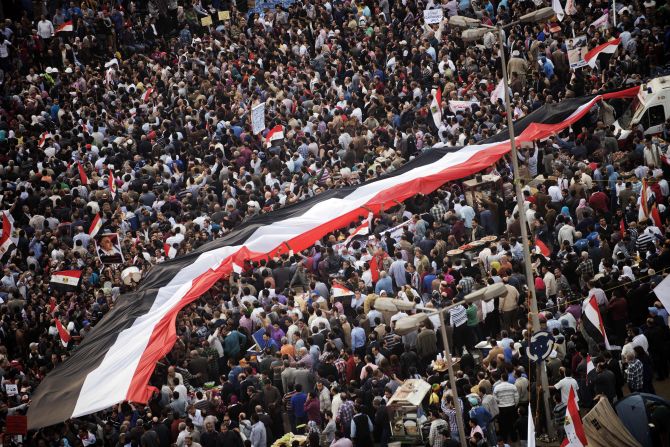

The Egyptian president and his Islamist friends had another think coming if they thought they could sneak a radical constitution past the people who fought for democracy in Tahrir Square.

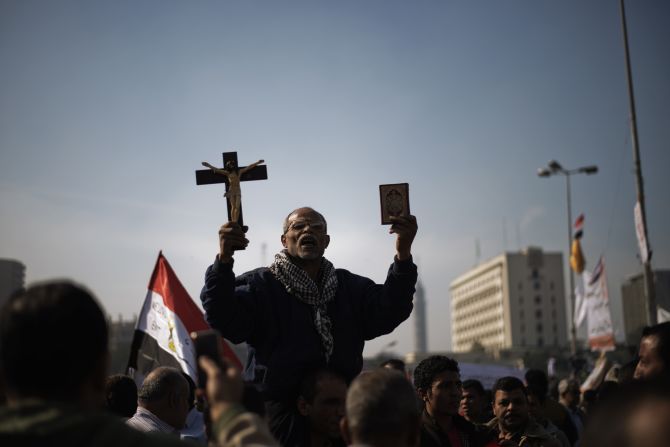

The draft constitution, and the political maneuvers that made it possible, have sparked the rage of liberal and secular Egyptians, who fear their dream of a truly free Egypt, with genuine equality for men and women, for people of all religions, is slipping away.

Why is democracy proving so difficult, perhaps impossible, to put in place?

One reason stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what democracy means. In places where dictatorship has prevailed, many hold the incorrect belief that democracy equals majority rule. They think democracy is a method for imposing the views of those who win elections upon those who lose.

Clearly, elections and majorities are a key element of decision-making in a democracy. But just as important is establishing basic principles of fairness and justice, creating a consensus of what the nation considers fair, and then developing the institutions and rules that guarantee they will survive through the ups and downs of politics.

News: Morsy aide blames upheaval on small, powerful minority

The creation of that foundation is known as the “constitutional moment,” a crucial time in a nation’s history when the people come together to decide what they believe, what truths they consider “self-evident.” It’s a moment that, ideally, sets aside the political fashions of the day. To succeed and create a stable future, it demands a measure of consensus.

Get our free weekly newsletter

The heart of the political battle in Egypt today lies in the proposed constitution, which President Mohamed Morsy insists he will bring up for a vote this week, a move the opposition calls an act of war.”

Many countries are familiar with this process. Americans have studied the evolution of the national consensus that led to the U.S. Constitution, a document so brief and brilliant it is regarded with a depth of reverence usually reserved for mystical religious texts. The European Union has been wrestling with a constitutional document, unable to create one that builds true consensus.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood and the more radical Islamists known as Salafis dominated the country’s first democratic elections and took their victories as a green light to ignore the views of the opposition.

Islamist parties had a head start in electoral politics, far ahead of secular and liberal parties. Under dictatorship, Islamist parties, though brutally persecuted, could carry their message through public services. The message of the Quran, now appropriated by Islamist parties, gave them a running advantage out of the political gate.

Liberal parties have a complicated case to make. It not easy to explain that you can be devoutly Muslim and support the secular rule of law, for example. It is also easier to explain the fairness of majority rule than the concept that in democracy it is crucial to protect minorities.

Bergen: Zero Dark Thirty: Did torture really net bin Laden?

With easy electoral victories, Islamists proceeded to implement their agenda, much faster than many expected. A spokesman for the Muslim Brotherhood, a man named Mohamed Morsy, had declared in 2011, “We are not seeking power.”

The make-up of the panel that would write the constitution sparked bitter conflict from the beginning.

The assembly, which should have made the most of the country’s precious constitutional moment, was supposed to include representatives of all segments of society, constitutional scholars, intellectuals, members of professional guilds, union members, writers; in short, views from all Egyptians.

The first panel was such a transparent power-grab by Islamists that the courts threw it out. A second assembly chosen in June proved just as controversial. Once again, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party used its muscle to pack it with supporters.

Non-Islamists, one by one, walked out of the constitution-writing body in frustration at the strong-arm tactics. Fearing the courts would invalidate the process, President Morsy essentially made himself dictator on November 22, the day after the rest of the world heaped praise on him for helping broker a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, providing a measure of political cover.

The opposition took to the streets, in what started to look like Revolution 2.0. Then Morsy ordered the constitutional assembly to hurry up and finish its work. In a mad rush, with a final session of 19 hours, the assembly approved a draft. By then, all the non-Islamists walked out.

The document, scheduled to go to voters for ratification on December 15, is an affront against democratic principles. It lays the groundwork for an eminently un-free future.

Opinion: Morsy miscalculating Egyptians’ rage

Trying to quiet the opposition, Morsy rescinded the decree that gave him absolute power, but he plans to go forward with a constitutional referendum, pushing forward a document littered with tiny seeds that can germinate into religious oppression. It is not surprising that it received high praise from Yasser Borhami, one of the country’s top ultra-conservative clerics, who raved about its many “restraints on rights” and concluded, “This will not be a democracy that can allow what God forbids, or forbids what God allows.”

The constitution says Sharia is the main source of legislation, and establishes that the (unelected) scholars of al-Azhar, the ancient center of Muslim learning, shall be consulted on Sharia matters. The draft speaks of equality for all, but orders that the state should “balance between a woman’s obligations to family and public work.” It also says the state must “protect ethics and morals and public order,” and guard the “true nature of the family.”

That alone is enough to justify every kind of interference in the personal lives of Egyptians, particularly women. The draft guarantees freedom of religion, but then says this is only for monotheist religions. It also bans “insulting prophets and messengers,” opening the door to curtailments of speech, especially on religious grounds, and creating fears for Buddhists, Hindus, and followers of the persecuted Baha’i sect. This is just a sampler of what the constitutional draft brings.

The opposition, at last looking coherent and unified, faces a steep road ahead. Sadly, so does Egypt.

President Morsy and his Muslim Brotherhood were not able to sneak their constitution in the dead of night. Instead, the entire country has seen the murkiness of the process. Instead of giving Egypt strong democratic underpinnings, they have built a brittle foundation for a deeply divided country.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Frida Ghitis.