Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a jazz and film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. He is a contributor to “The Oxford Companion to Jazz.”

Story highlights

Gene Seymour: Ravi Shankar brought classical Indian music to a global audience

He says he was legendary in India when he made cross-genre connections

The Byrds hip to Shankar before Beatles, but sitar could soon be heard on their records

Seymour: His sound transcended pop associations to carve out singular spot in music

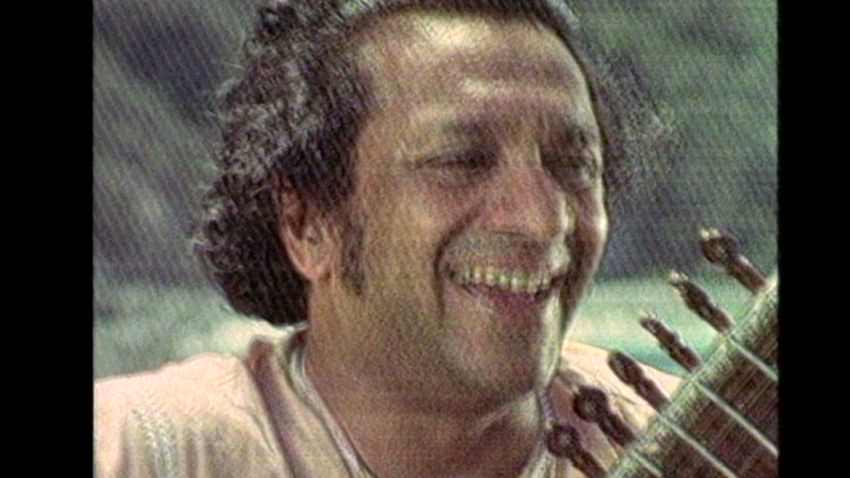

“Beauty” seemed somehow insufficient a description for the sounds that came from Ravi Shankar’s sitar in a concert hall. It was as if nature itself were being replicated on the stage, whether it was gentle summer rain or late-autumn wind having its way with the landscape. There would be intense engagement between Shankar and his ensemble as they summoned into being tempests of interlocking phrases that seemed to coil and unravel at will. The audience would be enraptured, transported, energized into enthusiastic applause.

And this was before the actual performance started.

“If you enjoyed the tuning up that much, I hope you enjoy the music even more,” Shankar can be heard saying on the recording of the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh addressing the appreciative, if nonplussed crowd at Madison Square Garden. It wasn’t the first, or last time he gently (at times, not so gently) reproved audiences who, even with the benefit of his warnings, took the preliminaries for the actual recitals. Some learned, some never did – and then there were those who really did enjoy the tuning-up as much as what followed.

Whatever his audience’s reaction, Shankar, who died Tuesday at age 92 after undergoing heart surgery, seemed to accept it all with benign imperiousness and regal warmth. As emissary for a classical tradition of Indian music, Shankar was winning over global audiences for that music in greater numbers than could have been imagined when he started learning the music of raga almost 70 years ago.

He was already close to legendary stature in India by the 1950s as sitar virtuoso, composer, conductor and director of All India Radio in New Delhi. He had also written scores for several Indian films, notably Satyajit Ray’s “Apu Trilogy” (1955-1959) whose international acclaim was a huge factor in increasing Shankar’s worldwide profile.

Get our free weekly newsletter

By the late 1950s, Shankar was making cross-genre connections with the likes of violinist Yehudi Menuhin and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, whose seminal 1961 recording of “My Favorite Things” was infused with modal inventions that carried the incantatory fervor of classic raga music. (Coltrane would name his son Ravi after Shankar. This year, by the way, Ravi Coltrane, who like his father plays tenor and soprano saxophone, released his finest album to date, “Spirit Fiction” on Blue Note Records.)

As all this indicates, Shankar was already well-known before the Beatles got involved. In fact, they weren’t even the first rock group to get hip to Shankar. That honor belonged to the Byrds, who recorded in the same World Pacific Records studios as Shankar did for producer Richard Bock. They in turn got George Harrison hooked on raga and Harrison began plucking the sitar on his own. (Dial up “Norwegian Wood” from the Beatles’ 1965 album “Rubber Soul” and you’ll hear that instrument poking out the theme.)

Harrison and Shankar met the next year and the “quiet Beatle” went to India to study sitar with the master. Back then, whatever the Beatles were interested in, the rest of the world was interested in, too. Brian Jones picked up the sitar on the Rolling Stones’ 1966 hit “Paint It Black” and the Byrds appropriated a sitar-sound (and a Coltrane riff) that same year for “Eight Miles High.” “Raga-rock” lasted just long enough to make the sitar part of the shorthand soundtrack of what’s often derisively labeled “the hippie era.”

Shankar was at best ambivalent about such associations. But his reputation, as with his music, transcended fashion to become its own singular, lasting presence in the world’s cultural firmament. Anyone who can make a sound check sound like genius packs substantial weight with the rest of the immortals.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Gene Seymour.