Editor’s Note:

Story highlights

Richie McCaw is second New Zealander to lead All Blacks to Rugby World Cup title

He played through the last three games of the 2011 tournament with a broken foot

McCaw is taking a six-month sabbatical from rugby in order to extend his playing career

The 31-year-old is hoping to explore his other passion of flying gliders and planes

It’s not easy carrying the burden of a sports-mad nation’s lofty expectations of world-beating dominance on your shoulders, especially on home soil, but Richie McCaw did it – with a broken foot.

Battered and bruised, and knowing that the All Blacks’ other iconic star player, Dan Carter, had already been ruled out for the rest of the 2011 Rugby World Cup, McCaw soldiered on for three crucial matches – four hours of on-field punishment

He hid the extent of his injury from fans, media, his coaches and teammates to keep alive his dream of being the first New Zealand captain to lift the Webb Ellis trophy for almost a quarter of a century.

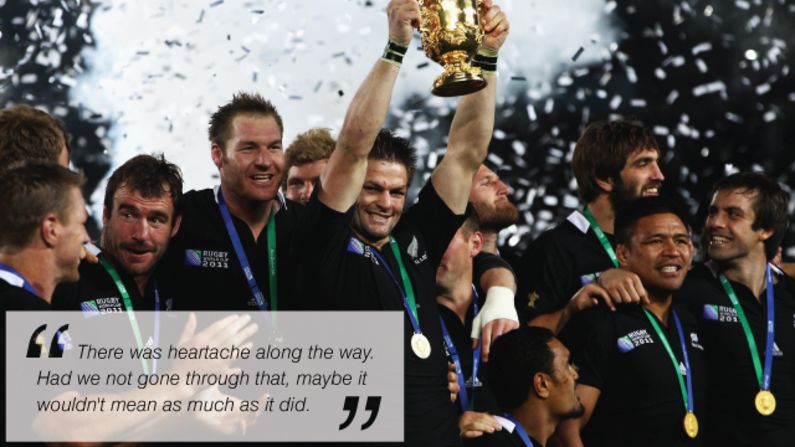

“The team had been number one in the world, or close to it, for a lot of years during the disappointment of not winning it,” McCaw told CNN’s Human to Hero series.

“We had a team that was good enough, but it doesn’t mean anything when you get to a tournament like that, if you don’t put it on the field where it counts.

“There was heartache along the way, but the appreciation of what you’ve done … I certainly appreciated it. The first emotions were sheer relief that we’d finally been able to knock it off. Had we not gone through that, maybe it wouldn’t mean as much as it did.”

When it comes to rugby, New Zealanders expect victory. Nothing else will do. Defeat is rare – and as painful as the body blows that are routine for those who play one of the world’s most physically demanding sports.

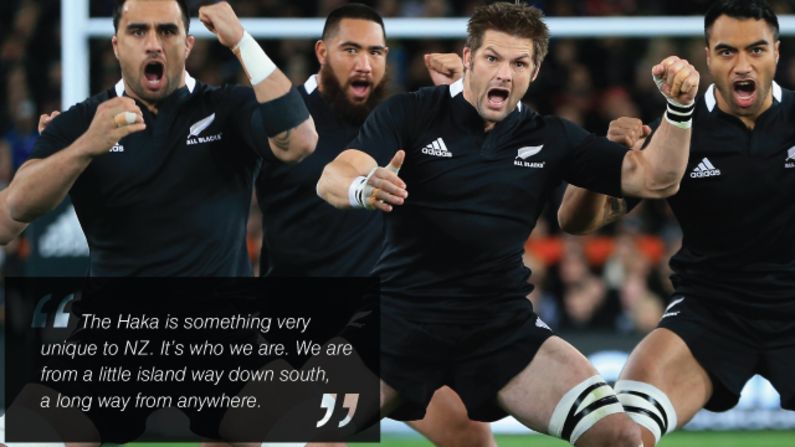

The traditional Maori war dance that the All Blacks perform before every match – known as “the Haka” – is one of the most fearsome, and highly anticipated, sights on the international rugby stage.

“It is something very unique to New Zealand,” McCaw said. “It’s who we are and were we come from … a little island way down south, a long way from anywhere. It’s a pretty powerful symbol of what the All Blacks and New Zealand is all about.”

So it was a matter of great national hurt that the All Blacks had not been world champions since winning the inaugural tournament in 1987, also at home.

“Up until the (2011) World Cup, everyone acknowledged, “Ah the All Blacks are great,’ but there was always a ‘but’ – I suppose because they hadn’t won the World Cup. To not have that ‘but’ anymore was pretty satisfying,” McCaw said.

McCaw knows all about winning. Having become first All Black to achieve a century of Test appearances during the 2011 World Cup, this year he reached 100 victories from just 112 appearances – a phenomenal strike rate.

He suffered heartbreak in 2003, losing in the World Cup semifinals to arch-rivals Australia, and in 2007 the All Blacks crashed out ignominiously against France in the quarterfinals, leading McCaw to reconsider his future as captain.

Instead of making wholesale changes, the New Zealanders regrouped and went into the 2011 tournament – once again – as hot favorites.

McCaw reached his century of caps in the third pool game against France, but his foot problem ruled him out of the match against Canada – and international rugby’s record points scorer Carter, who was to replace him as captain, then suffered a tournament-ending injury in training.

“I didn’t know what to say to Dan,” McCaw recalls in his autobiography “The Open Side.”

“Here’s a guy, a decent humble man, acknowledged to be the best of his generation, perhaps of any generation, who’s been crocked at the top of his game just when he’s about to perform on the biggest stage.

“I’ve had the odd moment since Dan went down this afternoon where I thought, ‘Jesus, it could be the two of us.’ But sitting with Dan, I know that it can’t be me now. Can’t happen. No moaning about my foot. Unlike Dan, I’ve still got a chance of playing and somehow, any old how, that’s what I’ve got to do.”

McCaw returned for the quarterfinal against Argentina, in which teammate Mils Muliaina became the second All Black to win 100 caps but then went off with a fractured shoulder. The injury crisis was mounting, and McCaw had his own worries.

“If I have to jump or run or push or tackle, I can do it – adrenaline’s a great painkiller. But when play stops and I have to walk or jog to a lineout or scrum 20 meters away, I’m really struggling.” he says in his book.

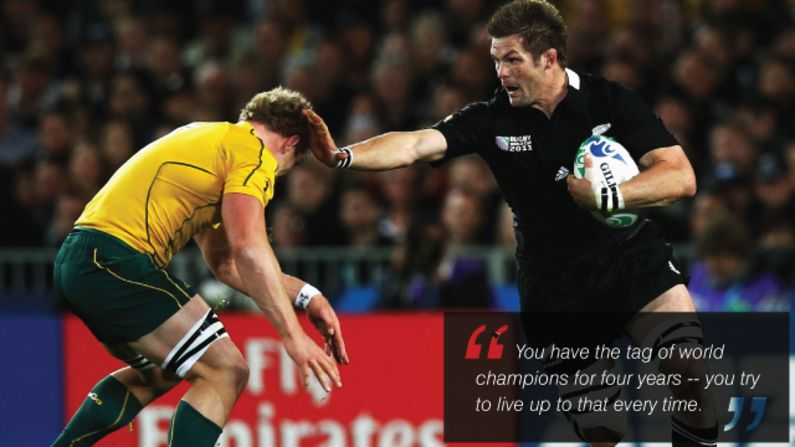

McCaw played the full 80 minutes in a 20-6 crushing of Australia, then held on to the bittersweet end in a nerve-wracking 8-7 win over France in the title decider – a rematch of the 1987 final that he had watched as a boy.

“I was about age 6 and watching it on TV. The image that I have in my head is John Kirwan scoring one of the tries,” he said.

“That sort of stuck with me I suppose. I thought it would be pretty cool to be like him.”

While Kirwan was one of New Zealand’s star backs, McCaw would go on to follow in the rugged boot prints of legendary forwards such Wayne Shelford, Michael Jones and Josh Kronfeld.

He has been named world player of the year three times, drawing both respect and anger from opponents and critics for his uncanny ability to tread the fine line between smart thinking and illegal play – as did one of his predecessors as skipper, 1987 World Cup winner Sean Fitzpatrick.

Having finally landed New Zealand’s holy grail, McCaw is hoping to play at the next World Cup in England in 2015, when he’ll be 35.

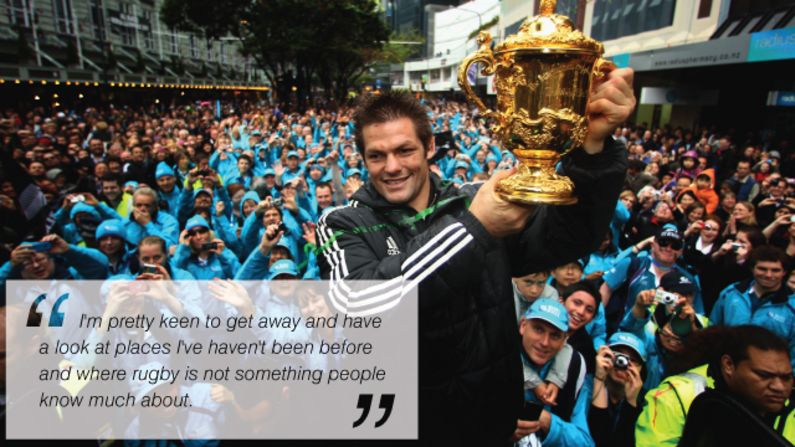

But after a long career as one of the most dynamic and influential forwards in rugby, it’s time to take a break – a six-month sabbatical in which he plans to get away from it all.

He has plenty of incentive to come back stronger – his last match was a shock defeat to England last month which ended the All Blacks’ 20-match unbeaten run.

“I hope having the time off will make me play a bit longer. So I’m taking it before I desperately need it, with the hope I’ll come back fresh mentally and physically,” he said.

“I’m pretty keen to get away and have a look at places I’ve haven’t been before and where rugby is not something people know too much about. That’s part of what wears you down a little bit, when you are living in fishbowl like you do in New Zealand, and it’s just nice to have a bit of time to be anonymous.”

McCaw has hinted that he will head to the U.S. and indulge his other passion – flying.

His grandfather was a fighter pilot during World War Two, and he has continued the family interest, being named an honorary squadron leader in the New Zealand Air Force.

He flies planes, helicopters and gliders, and has even narrated an aviation TV program.

“Dad flies, his brothers fly, a couple of my cousins fly, my aunty flies. We’ve got flying in common. When I go home to the old man we sit and talk way more about flying than rugby,” McCaw says in “The Open Side.”

“Gliding teaches you that you’ve got to be prepared as you possibly can for whatever contingencies of terrain and weather might eventuate when you’re up there. At the same time, you have to acknowledge that no matter how much you prepare, no matter how thorough you are, you can’t anticipate everything that Nature and Fate throw at you.”

When he returns from his sabbatical in mid-2013, McCaw knows that the rugby world will be trying to knock him and the All Blacks off their pedestal.

“A lot of people ask me what’s left to achieve or why do you still want to play. I guess you readjust the challenges,” he told CNN.

“You have the tag of world champions for four years – you try to live up to that every time. I know what it’s like, I’ve tried to knock off the world champs the following year.

“If we have that sort of goal, that sort of attitude, hopefully we will keep that level where it needs to be.”