Editor’s Note: Shyam Sankar is director of forward deployed engineering at Palantir Technologies. Follow him on Twitter: @ssankar He spoke at TED Global in Edinburgh in June. TED is a nonprofit dedicated to “ideas worth spreading,” which it makes available through talks posted on its website.

Story highlights

Shyam Sankar: Some say computers could attain artificial intelligence superior to humans

A more realistic approach is to envision computers aided by human intelligence, he says

Computers can spot patterns from the past but can't anticipate as people can, he says

Sankar: Human thought, aided by computer power, can make sense of "big data"

In 1997, Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer. It seemed like a watershed moment, recalling the rise of the machines long prophesied in science fiction.

Yet in 2005, a freestyle chess tournament featured teams of humans partnering with computers in various combinations. Shockingly, two amateurs using three fairly weak laptops emerged victorious, beating grand masters and supercomputers in turn.

This contrast is fittingly emblematic of two great visionaries of computer science, Marvin Minsky and J.C.R. Licklider. Minsky wrote canonical theories of self-replicating artificial intelligence and co-founded MIT’s A.I. lab.

Licklider proposed an alternate vision in his landmark paper, “Man-Computer Symbiosis”. In Licklider’s view, human intelligence should be complemented by machines, not replaced: “Men will set the goals, formulate the hypotheses, determine the criteria and perform the evaluations. Computing machines will do the routinizable work that must be done to prepare the way for insights and decisions. …”

Technology is too often viewed through a utopian or alarmist lens, and it’s worth noting that Licklider’s work spanned the sublime and sobering alike. He presaged much of the Internet revolution, and his research led to such breakthroughs as the modern graphical user interface. He also worked on a computer-aided missile defense system designed to collect and present data to a human operator, who would choose the appropriate response.

Get our free weekly newsletter

It’s easy to argue that life and death decisions should never be left to machines, but Licklider’s vision was much broader, recognizing technology as an enabler for many human capacities. Since Kasparov and Deep Blue squared off, we have seen numerous examples of man-computer symbiosis, while A.I. relying solely on computers as Minsky theorized it remains tantalizing, yet distant.

TED.com: Robots that fly…and cooperate

In terms of catalyzing human potential, the triumph of the chess amateurs in 2005 was just one glimpse of the future. Foldit, an online video game, allows nontechnical, nonbiologist players to visually “fold” protein structures, while computers calculate the chemical interactions corresponding to each arrangement.

In 2011, Foldit players needed only 10 days to produce an accurate 3-D model of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus, a protease whose structure had stumped scientists for 15 years.

It was an astonishing triumph of human visual-spatial reasoning, and one of the first major scientific advances to come from playing a video game (though plenty of software engineers I know would argue that video games activate much more creativity than we care to acknowledge).

The tension between the Minsky and Licklider visions has certainly been amplified in the age of so-called big data. Now, consider that most of what we think of as “big data” is created by deliberate human action: phone calls, Web logs, credit card transactions, etc. When we hear about big data “solutions,” they tend to focus on computational approaches – storage, search and processing – with human intuition largely absent. Yet the unraveling of big data into meaningful insight may depend just as heavily on the human side of the equation.

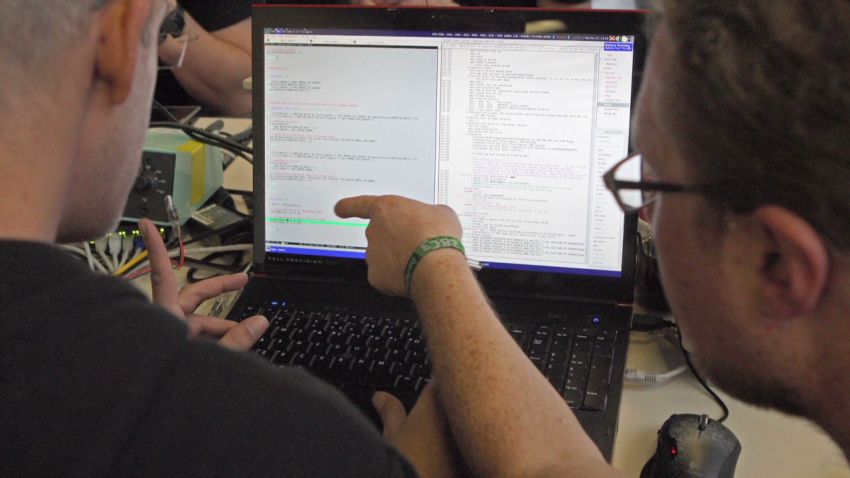

Why is this? “Pattern recognition” is a frequent A.I. refrain, but computers can’t learn to spot patterns they’ve never seen. The high-value targets in big data are invariably human: highly adaptive adversaries such as terrorists and cybercriminals whose ingenuity frustrates even the most advanced algorithms.

TED.com: My seven species of robot

Yet even the nimblest fugitives leave clues, even patterns – they’re just buried in an expanding universe of data, a challenge that intensifies as we seek still more data, hoping it will yield more insight.

Adaptive adversaries require adaptive responses, and this begins with asking questions rooted in human intuition. While technology can certainly be a force multiplier for good or evil, it’s difficult to imagine a pure A.I. approach reverse-engineering the machinations of a terrorist mastermind.

When U.S. intelligence tracked down Osama bin Laden, it was a function of brilliant, resourceful people asking questions and testing hypotheses using a variety of technologies.

Cybercriminals, as explored in my first TED talk, tend to target the allegedly weakest links in the network: people. Yet how weak is something that can learn in ways even the most robust automated systems can’t?

TED.com: All it takes is 10 mindful minutes

Cyber security might always be an uphill, defensive struggle as techniques and technologies raise the stakes on both sides. Remember, though, that cyberwarfare is ultimately a human endeavor. Bot-nets, scripts and other automated tools play key roles, but they don’t exist in a vacuum. This cuts both ways: Sooner or later, everyone makes mistakes, even evil genius types. That said, the enemy may well be two amateurs with a few weak laptops.

Aspiring good guys must be absolutely relentless in refining the intersection of brainpower and computing power, each of which is vulnerable in isolation.

Sometimes, the right combination of humans and technology can reshape the data landscape itself. In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, my company partnered with veterans’ organization Team Rubicon to coordinate relief efforts in the Rockaways. It began with identifying the hardest-hit areas and greatest needs.

Soon, as help poured in, the focus shifted to tracking projects, allocating manpower, and coordinating more than 10,000 volunteers in real time. Through rapid iteration, a group of determined people using low-friction technology had created a vast, self-regulating system. Each discrete data point was simple enough – the status of a project, levels of need, locations of assets – but in aggregate, the effect was transformative.

While experience teaches that each approach has its caveats, we have every reason to be excited about the possibilities of human-computer symbiosis. Almost 50 years since the identification of Moore’s Law, and 10 years since the human genome was first sequenced, humans and machines are beginning a new arc of re-imagining and discovery – together.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Shyam Sankar.