Story highlights

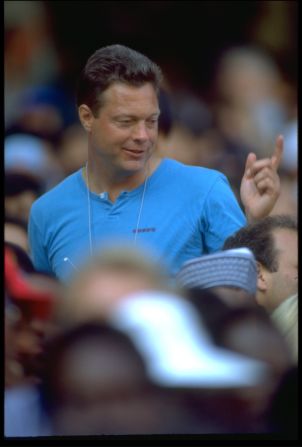

CNN spoke to the president of the World Anti Doping Agency John Fahey

WADA president believes it's better current doping allegations in sport are out in the open

Fahey criticizes FIFA for not doing enough on checking for banned substance EPO in the past

Tuesday sees Tyler Hamilton appear at Operation Puerto trial in Spain

Somewhere, in a parallel dimension, when cyclist Tyler Hamilton appears on live video link beamed in to a court room in the Spanish city of Madrid on Tuesday, his testimony detailing the breadth and impunity of doping within his sport would send shock waves across the world.

But, in the here and now, such is the public’s current fatigue of drug revelations in sport that his appearance at the trial of the Operation Puerto scandal – where Spanish doctor Eufemiano Fuentes is accused of masterminding a blood doping network at the highest level of professional cycling – will be met with little more than a collective shrug.

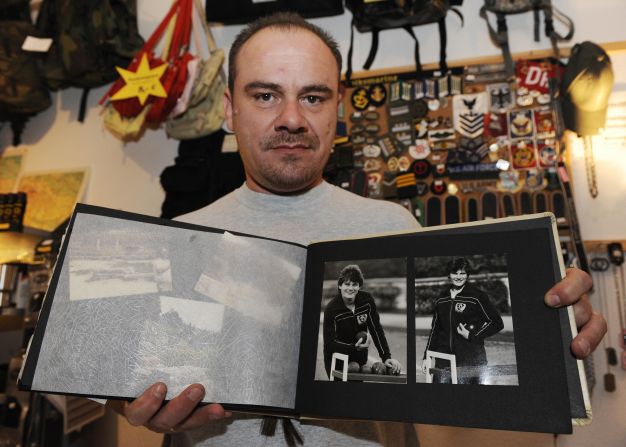

Hamilton was an American cyclist who won a gold medal at the 2004 Olympics before riding with Lance Armstrong in the Tour de France. He has already detailed his own drug-taking exploits in his book “The Secret Race,” helping to lift the lid on the murky, dangerous and in some cases criminal world of performance-enhancing drugs.

But those revelations – which implicated Armstrong as much as himself – were just the tip of the iceberg.

Read: Armstrong immortalized in graffiti ‘doping’ artwork

From Armstrong’s carefully managed but ultimately soulless confession to doping fraud on Oprah to the release of a damning report by the Australian Crime Commission – the government’s top criminal intelligence body – in to widespread doping in some of the country’s top sports and the ongoing Operation Puerto trial, the fidelity of sportsmen and women is increasingly being called into question.

“I don’t think anything has changed, there have been doping cheats in sports for a long, long time, and there are still doping cheats in sports,” John Fahey, president of the World Anti Doping Agency, told CNN.

“What we are seeing in more recent days is a number of revelations which give us some sort of indication that, in some cases, it’s quite widespread. I think we now know there was a period in cycling where it was extremely widespread.”

Poachers versus gamekeepers

But while the reputation of sports stars has taken a hit, the people charged with catching them – the various different governing bodies and, at the top, WADA – remain one step behind the dopers. Armstrong, after all, claimed correctly that he never failed a drugs test.

Yet for the man who heads the world’s top anti-doping body, the revelations are a move in the right direction, rather than proof of failure.

“Has cycling fixed itself up? Well, I don’t know,” admitted Fahey, before suggesting that the revelations “makes us all think about the problem, and that’s not such a bad thing.”

“I would much sooner see all of these things about doping in sport on the surface than to know that there was doping in sport and we don’t know about it,” he added.

Despite the public’s doping fatigue, the revelations that have emerged from the Operation Puerto trial so far have been shocking. Fuentes has been accused, along with his sister and three other defendants from various other cycling teams, of running a blood doping ring that involved transfusions of re-oxygenated blood.

Blood doping involves using hormones or transfusions to boost the numbers of red cells in the body. This can increase a sportsman or woman’s ability to carry oxygen to the muscles, a distinct advantage in endurance sports.

Hotel transfusion

Several top names in cycling have been implicated. According to a 2006 report in Spanish newspaper El Pais Tyler Hamilton paid Fuentes at least $47,000 for the procedure. But doping wasn’t a criminal offence in Spain in 2006 when Fuentes was arrested and hundreds of bags of blood from his clients seized. Instead they have been accused of endangering public health, charges they deny.

WADA’s own medical expert Dr. Yorck Olaf Schumacher gave a damning appraisal of the health risks that many of the cyclists faced when he testified in Spain, according to Cycling News website which is covering the trial. “Extracting half a liter or a liter of blood presents a greater risk than extracting the usual amounts. That’s up to 20% of the body’s total, whereas you would only extract 1% for a blood analysis,” he said.

“A hotel does not fulfill the conditions required for a transfusion,” he added, referring to the alleged unsanitary conditions in which the blood doping took place. “A cool bag for picnics isn’t the best thing for transporting blood.”

Schumacher also raised the possibility that cyclists would have been exposed to greater risk of contracting diseases such as HIV and hepatitis.

“We’ve been fighting this case now for the best part of seven years,” said Fahey, before turning his attentions to other sports.

“Those hundreds of blood bags that appear to belong to many different types of sportsmen and women, so (it’s) not just one sport. We want to know who they are, we want to know what’s in those bags, and all of that knowledge and information passed on to the authorities that will take action against the owners of that blood.”

Soccer stars implicated?

Many of the names attached to those damning, currently anonymous blood bags could contain the names of well-known soccer players. During the trial Fuentes told the court that he had many clients in the world of soccer, athletics and boxing. But the judge ruled that Fuentes would not be compelled to reveal names.

Fuentes’ revelations have not gone unnoticed by WADA officials, who believe soccer’s governing body FIFA could do much more to tackle alleged doping in the game – particularly the use of EPO, or erythropoietin, a hormone produced by the kidney that is injected to stimulate red blood cell production that has long been used by cyclists.

“I acknowledge that under the world body, FIFA, there is an anti-doping program,” said Fahey. “They can do more, they’ve got to test players, many more of them, and make sure they are testing for the drug of choice EPO. Otherwise they are paying lip service to the issue rather than convincing anybody that they’ve got an effective program.”

The answer, according to Fahey, is to insist on a biological profile and passport for each player, an issue he raised with Sepp Blatter, the secretary general of FIFA, when they met last week. FIFA announced after that meeting that it will introduce biological profiles at June’s Confederations Cup tournament in Brazil. The scheme will see a biological profile taken from each player two months before so that any marked changes in that profile at the tournament could point to blood doping or hormone use.

“I would like to see, particularly team sports, take up the athlete’s biological passport,” Fahey said.

“There is absolutely no reason why in the major codes of football, and in the major sporting events right throughout the world they shouldn’t all (have) the tool known as the biological passport. That will do a lot to stamp out doping in sport, and most of those major codes can easily afford the cost of running that program.”

But, for now, the focus remains on cycling, Operation Puerto, Fuentes and Tyler Hamilton’s testimony. Fahey hopes that the trial will be a watershed moment for doping in sport.

“This is not the first court case that we’ve had on this subject over the past seven years, but we will continue to exhaust all legal rights,” Fahey said.

“We believe it is important enough to do that. I hope this may well be the final court case that we have to participate in.”