Story highlights

The Yemeni community of South Shields, England is one of the UK's oldest Muslim populations

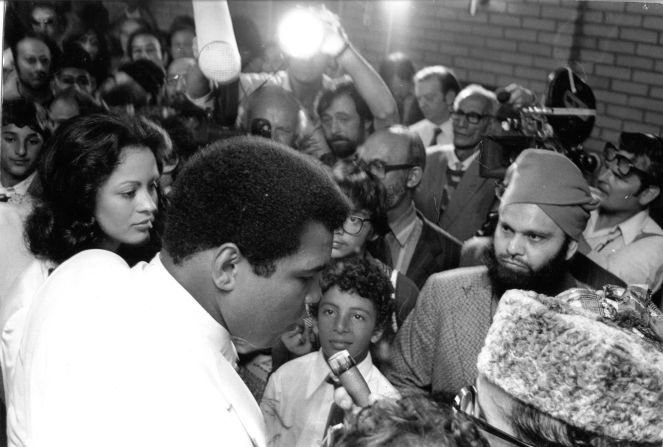

In 1977, boxer Muhammad Ali visited and had his marriage blessed in the mosque

Artist Tina Gharavi has created an exhibition documenting the stories of the community's elders

She says she wants to capture the tales of this disappearing world

Film-maker and artist Tina Gharavi grew up idolizing Muhammad Ali, the trailblazing American boxing great who was a hero to her Iranian father and millions of others around the world.

“My dad had incredible love for him,” she told CNN at the opening of her latest exhibition, “The Last of the Dictionary Men,” currently on display in London’s Mosaic Rooms gallery. “It was the first time I saw a very strong black person, who was so unapologetic and beautiful.”

So when she moved to South Shields – a coastal town with a maritime heritage in northeast England – and heard that one of the 20th century’s most celebrated athletes had had his marriage blessed in an Islamic ceremony at the local mosque, she found it hard to believe.

“I said ‘What?’ I’d lived in the north for eight years and never heard about it. I knew I had to find out more.”

Ali, she learned, had visited South Shields in 1977 with his new wife, Veronica Porsche, and their baby daughter Hana, in response to an invitation to come to the area to raise money for the Boys Club, a British charitable organization.

The visit – which drew thousands out lining the streets to watch his procession through the town – reached its high point with a marriage blessing ceremony by the imam at the town’s Al-Azhar Mosque.

Intrigued by the story, Gharavi spent two years making a film – “The King of South Shields” – about Ali’s unlikely visit, which led to an enduring relationship with the town’s longstanding Yemeni community, whose mosque had hosted the boxer and for whom the day had provided an important validation of their sometimes tenuous place in British society.

In the process of making the film, she realized that many of the elders of the South Shields Yemenis – one of the UK’s oldest Muslim and Arab communities – were passing away, their rich stories vanishing with them.

“I was seeing something that was about to disappear and I thought this is so fascinating, I need to capture this,” she said. “Now their world is almost gone.”

Read more: Lebanese women take on religious judges who call rape a ‘marital right’

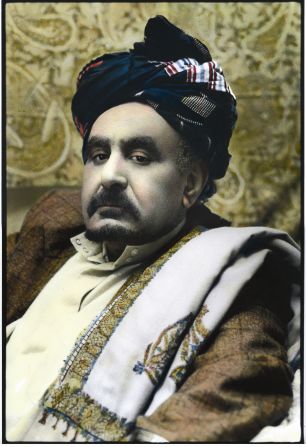

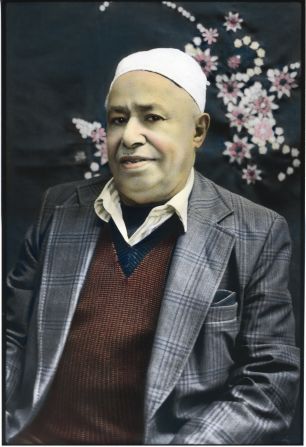

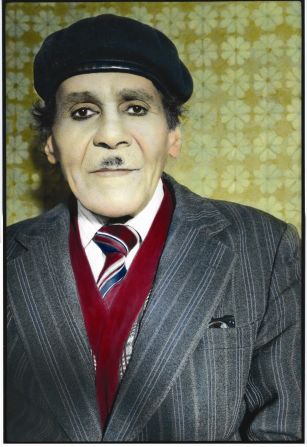

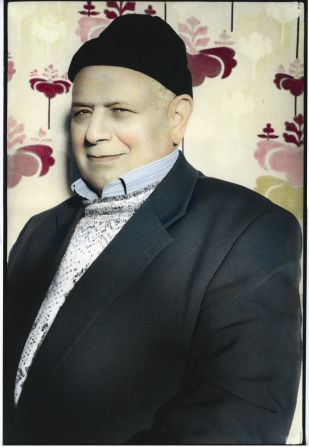

She set about preserving some of that world with “The Last of the Dictionary Men,” which features a series of interviews with 14 of the last surviving members of the first generation of South Shields’ Yemenis, recounting their experiences as migrants to the U.K., and a series of large portraits of the men by Egyptian photographer Youssef Nabil.

The outsized portraits, said Gharavi, hand-colored in the style of old Egyptian movie posters, were intended to present the men “in a way that aggrandizes them,” in contrast to the “social realist” depictions that had typically been used to portray their community.

“Whenever they were shown, they’d typically be in the mosque, everything would look very miserable and a bit dirty,” she said. “I thought that’s not who they are. They were funny, they would flirt with me and were full of life.”

The name of the exhibition, she said, referred to lines written by the Yemeni poet Abdullah al-Baradduni, who wrote in 1995 that “our land is the dictionary of our people.”

The story of South Shields’ Yemeni community began in the 1890s, when seamen from the British ruled Aden Protectorate – now part of modern day Yemen – began working on British ships, eventually finding their way to port towns in Britain. The UK’s first mosque was opened in Cardiff, Wales, by Yemenis who had come to Britain as seamen.

Gharavi said the Yemenis were recruited by the British as they made good sailors – they didn’t drink, and could handle the heat of the engine room furnaces well.

During the First World War, the British government began encouraging Yemeni men into the country to make up for a manpower shortage brought about by the conflict. By the war’s end, the Yemeni population of the northern shipping town had risen to about 3,000, and as many as 800 had been killed on merchant navy supply ships at sea.

“They were working on ships that the German were very keen to bomb, so there’s an extraordinary number of Yemeni men who died,” said Gharavi.

But the new arrivals were not initially welcomed by the public at large. Discrimination meant they found it hard to find accommodation, with the seamen mostly forced to live in boarding houses – the first of which opened in the town in 1909 – largely isolated from the wider community.

After the war, the boarding houses suffered attacks intended to drive the Arabs from the town. Perceptions of unfair treatment in the workplace led to riots in 1919 and 1930, and eventually led to the council segregating the community by building an estate to house the Yemenis.

Read more: Can Iraq’s geeks save the country?

But by the 1940s, attitudes towards the community began to change, and Yemenis began marrying into the wider community. As part of her research, Gharavi commissioned a survey team to ask 100 people on South Shields’ main street about their ancestry, and about one in four claimed some Yemeni heritage.

Today, many of those South Shields locals – who speak with the distinctive northeastern accent known as Geordie – are returning to Yemen to reconnect with the culture of their forefathers, said Gharavi. South Shields’ Arab community is often held up as an example of an immigration success story.

“The Yemeni have been incredibly dutiful to this country,” she said. “They’ve worked very hard for this country, and they love Britain very much because they know what they’ve gotten from here.”

For his part, Saeed Mohamed Aklan Ghaleb, one of the men profiled in the exhibition, was nonplussed by the attention.

“When the people came to talk and take the picture, we didn’t know this would happen,” he said, bemused by the art crowd gathered at the exhibition’s opening.

He arrived in South Shields as a seaman in 1967, and returns every two years. “It brings back memories,” he said of the portraits, adding that he had a copy of his portrait hanging in his home.

Gharavi said that in her eyes the community’s humility was the reason the community had integrated into Britain so successfully.

“They go into a community and they assimilate, they adopt the rule of where they live and that’s the reason the Yemeni have sort of disappeared in a sense.”

It was part of the reason she thought their story should be heard.

“There is that swing at the moment in Britain – a concern that ‘These guys are invading, this is problematic.’ It’s not problematic. These guys have been here since 1890 and it’s going fine.”