Editor’s Note: Arun Kundnani is author of the forthcoming book “The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, extremism, and the domestic War on Terror,” to be published by Verso Press in January 2014. He teaches terrorism studies at John Jay College, New York.

Story highlights

Debate has ranged widely over how to prevent terrorist attacks

Arun Kundnani says answer is not more and more surveillance

He says mosque leaders are fearful of engaging in discussion with radicals

Kundnani: Don't toss people like Tamerlan Tsarnaev out of mosques; confront them

Since the bombing of the Boston marathon – in which three people, including a child, were killed and more than 200 injured – attention has naturally focused on what could have been done to prevent it.

Some, such as Rep. Peter King, the New York Republican who chairs the Homeland Security Committee, have argued for increased surveillance of Muslims in the United States. Local police departments “have to realize that the threat is coming from the Muslim community and increase surveillance there,” he says.

Others have asked whether leads were properly followed and if better sharing of information between agencies would have helped thwart the bombing.

However, the government, with its $40 billion annual intelligence budget, already amasses vast quantities of information on the private lives of Muslims in the United States. The FBI has 3,000 intelligence analysts working on counterterrorism and 15,000 paid informants, according to Mother Jones.

Exactly how many of them are focused on Muslims in the United States is unknown; there is little transparency in this area. But, given the emphasis the FBI has placed on preventing Muslim terrorism, and based on my interviews with FBI agents working on counterterrorism, there could be as many as two-thirds assigned to spying on Muslims.

Taking the usual estimate of the Muslim population in the United States of 2.35 million, this would mean the FBI has a spy for every 200 Muslims in the United States. When one adds the resources of the National Security Agency, regional intelligence fusion centers, and the counterterrorism work of local police departments, such as the New York Police Department (where a thousand officers are said to work on counterterrorism and intelligence), the number of spies per Muslim may increase dramatically. East Germany’s communist-era secret police, the Stasi, had one intelligence analyst or informant for every 66 citizens. This suggests that Muslims in the United States could be approaching levels of state surveillance similar to that which the East German population faced from the Stasi.

Yet, as the Stasi itself eventually discovered, no system of surveillance can ever produce total knowledge of a population. Indeed, the greater the amount of information collected, the harder it is to interpret its meaning. In the majority of terrorist attacks in recent years, the relevant information was somewhere in the government’s systems, but its significance was lost amid a morass of useless data.

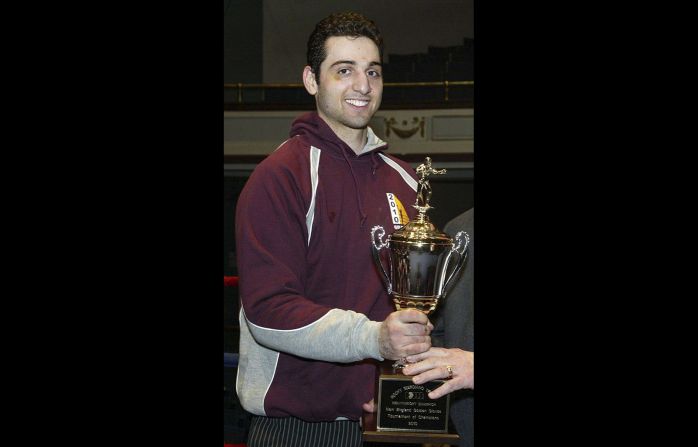

What is obscured by the demands for ever greater surveillance and information processing is that security is best established through relationships of trust and inclusion within the community. The real missed opportunity to intervene before the bombs went off in Boston likely came three months earlier, when bombing suspect Tamerlan Tsarnaev stood up during a Friday prayer service at his mosque - the Islamic Society of Boston, in Cambridge - to angrily protest the imam’s sermon.

The imam had been celebrating the life of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., which Tsarnaev thought was selling out. According to one report, Tsarnaev was then kicked out of the prayer service for his outburst.

Since 9/11, mosque leaders have been under pressure to eject anyone expressing radical views, rather than engaging with them and seeking to challenge their religious interpretation, address their political frustrations, or meet their emotional needs.

That policy has been forced on mosques by the wider climate of excessive surveillance, which means mosques are wary of even having conversations with those perceived to be radicals, for fear of attracting official attention.

The fear is that every mosque has a government informant listening for radical talk. Unsurprisingly, this means most people are reluctant to engage with young people expressing radical views, who instead tend to be ejected from the congregation.

The Tsarnaev brothers were said to be angry about U.S. foreign policy in Afghanistan and Iraq, possibly drawing parallels with their own experiences as refugees from Russia’s brutal wars of counterinsurgency in the Caucasus. But because discussions of foreign policy have been off-limits in mosques since 9/11, they were unlikely to have had their anger acknowledged, engaged, challenged or channeled into nonviolent political activism.

The heavy surveillance of Muslims has meant there is no room for mosques to engage with someone like Tamerlan Tsarnaev, listen to him, challenge those of his ideas that might be violent, or offer him emotional support. Instead, Muslims have felt pressured to demonstrate their loyalty to America by steering clear of dissident conversations on foreign policy.

Flawed models of the so-called “radicalization” process have assumed that the best way to stop terrorist violence is to prevent radical ideas from circulating. Yet the history of terrorism suggests the opposite is true.

Time and again, support for terrorism appears to increase when legitimate political activism is suppressed - from the French anarchists who began bombing campaigns after the defeat of the Paris Commune, to the Algerian National Liberation Front struggling to end French colonialism, to the Weather Underground’s “Declaration of a state of war” after state repression of student campaigns against the Vietnam War.

Reconstructing the motivation for the bombings is fraught with difficulty; there can be little certainty in such matters. But pathological outcomes are more likely when space for the free exchange of feelings and opinions is squeezed.

As many community activists and religious leaders argued in Britain in the aftermath of the 7/7 terrorist attacks on the London transport system in 2005, the best preventive measure is to enable anger, frustration and dissent to be expressed as openly as possible, rather than driving them underground where they more easily mutate into violent forms.

These activists put this approach into practice, for example at the Brixton mosque in south London, by developing initiatives in the community to engage young people in discussions of foreign policy, identity and the meaning of religious terms like jihad, in order to counter those who advocate violence against fellow citizens. It is difficult to measure the success of such programs. But many see them as having played an important role in undermining support for terrorism. In what must seem a paradox to backers of East German levels of surveillance like Peter King, more radical talk might be the best way of reducing terrorist violence.

No one could have predicted from Tsarnaev’s outburst that, a few months later, he would be suspected of carrying out an act of mass murder on the streets of Boston. And we don’t know what would have made a difference in the end. But a community able to express itself openly without fear, whether in the mosque or elsewhere, should be a key element in the United States’ efforts to prevent domestic terrorism.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Arun Kundnani.