Story highlights

To participate in online society today, people must sacrifice some level of privacy

Professor: In a way, we're all at least minor Internet celebrities -- deal with it

Experts encourage users to take more control of their online lives

Teens shrewdly coding messages is one way to restrict information

The controversy over National Security Agency data mining has spawned columns featuring ominous references to Orwell and Kafka, reassurances from politicians and jokes (made on the Internet, of course) about the government peeking through the blinds.

But often lost amid it all is a simple fact: This is the world we have made.

Oh, maybe you didn’t make it, and I didn’t make it, but enough of us voted for it with our ballots and pocketbooks and Web surfing that it has come to pass regardless.

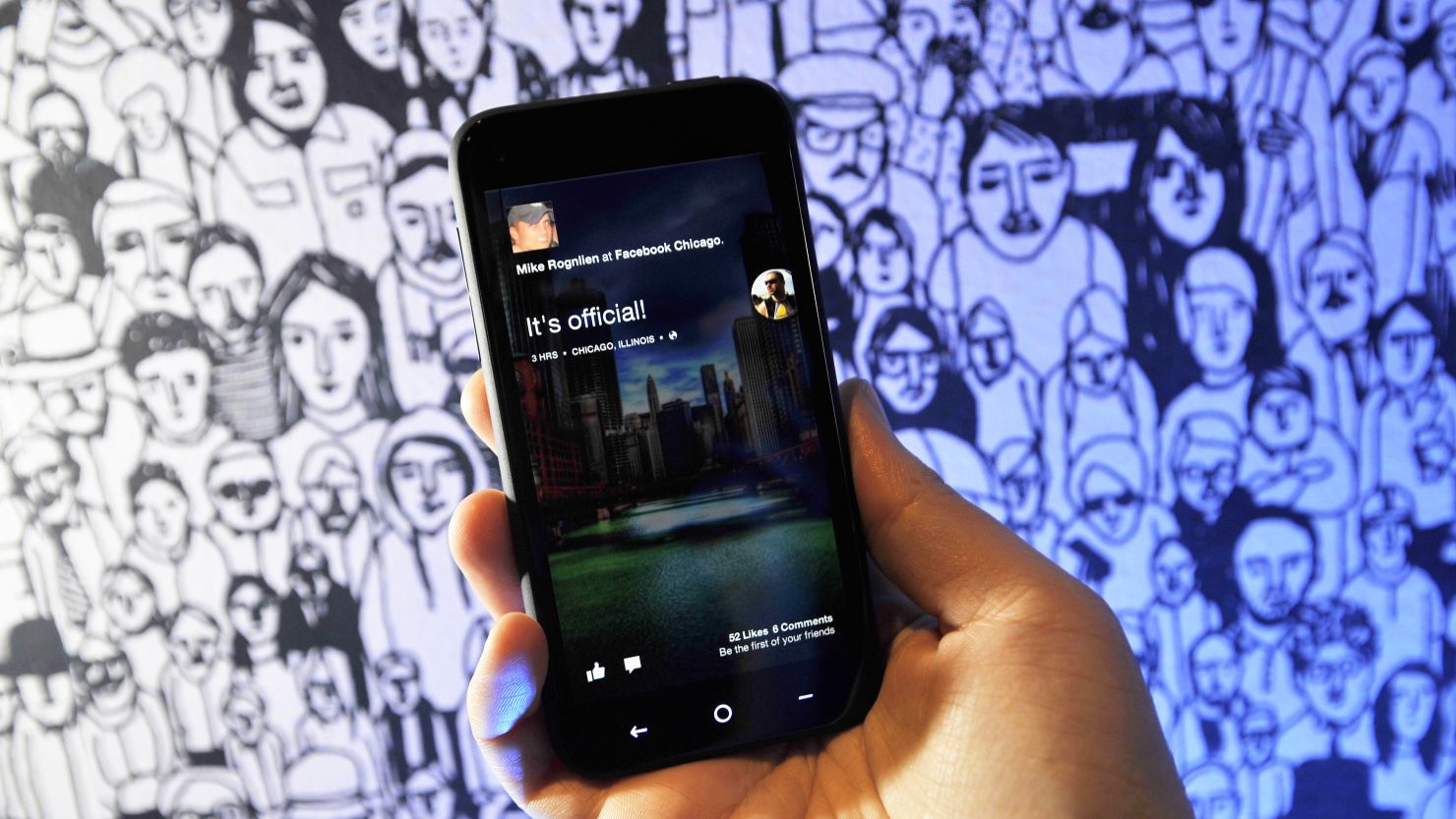

Like it or not, the online world today is one in which we’re expected to participate. Whether because of peer pressure, sheer convenience or clear-eyed decision making, we join social media sites, order merchandise online, store things in the cloud and burnish our “digital brand.”

Meanwhile, we don’t read End Use License Agreements (bo-ring!), freely exchange personal information on Facebook and insults on Twitter, enjoy tailored recommendations on Amazon and swipe key tags to take advantage of targeted discounts at grocery stores – places where we often take pleasure in tabloid covers revealing invasions into other people’s privacy.

So you thought paparazzi-level scrutiny was only for celebrities? Syracuse University’s Anthony Rotolo has news for you: Thanks to the Internet, we’re all celebrities on some level now.

After the crash: License, registration and cellphone, please

“In reality, we’re all kind of on ‘Big Brother’ – on a reality show,” says Rotolo, a professor who runs the Starship NEXIS lab, focusing on social networking and new technologies. “Whenever I give a talk, whenever you give a talk, there’s going to be someone live-tweeting it. There’s going to be somebody posting a picture on Facebook. We are redefining celebrity in this age, and anybody at any time could be speaking publicly without realizing it.”

At its most extreme level, our hunger for sociability can turn minor incidents into major media firestorms, thanks to the Web’s viral capabilities. One minute you’re leaving a crummy tip; the next your message is all over the Web. One minute you’re a bullied bus monitor; the next someone is raising hundreds of thousands of dollars on your behalf.

But even small pebble drops into the vast pool of the Internet can leave big ripples. How often have you made a purchase on one site – or even just done some online window-shopping – to find that ads on dozens of other, unrelated sites were suddenly pitching you the same product? And what about that misunderstood text that turns into a local flame war? And never mind the seemingly narrow online sleuthing that becomes an online lynching.

“A lot of stuff (online) plays out in public,” says Rotolo, who believes we’re still learning how to deal with it all.

So is it possible to have an active digital social life and still preserve a measure of personal privacy? Experts say yes.

‘A choice’

Leaving a trail of digital footprints makes some people uncomfortable – whether they’re thinking about Big Brother or simply being judged by their extended friends and family. You have to set limits, says Daniel Sieberg, author of “The Digital Diet.”

“What we choose to share or consume through social networks is a choice. Sounds simple, but sometimes we seem to forget that concept,” he says. “In writing the book, I felt that I was sharing too much personal information in a public setting and not also connecting with friends and loved ones in a more direct fashion, too.”

He draws a line between his personal and professional lives.

“Occasionally I will share photos of our 2-year-old daughter on social networks but it’s only in rare cases and I try to send unique photos to my family,” he says. “That’s a decision we made about keeping some of our private life away from the digital lens.”

Gary Vaynerchuk, an entrepreneur and founder of the social media brand consultant VaynerMedia, has the same outlook as Sieberg. He’s aggressive with his business and himself; he’s reserved when it comes to his wife and children.

Vaynerchuk acknowledges that the all-seeing Web can be a double-edged sword.

“I have thousands of hours of material out there in which I curse every third word,” he says. “There’s a lot of me out there. I have to deal with that.”

But mixing it up socially doesn’t bother Vaynerchuk, who often engages with strangers online. For the most part, he says, “we need to start respecting the fact that we’re totally in control” of our online personas.

Sure, there are times when Vaynerchuk is tagged or referenced in other people’s content. But that’s part of life now, he says. Get used to it.

Panic and indifference

Not that some people are too worried about their privacy online. A Pew Research Center/Washington Post survey reported that 56% of Americans found NSA tracking calls to investigate terrorism “acceptable.”

And on Friday, Gizmodo writer Kyle Wagner published a widely shared column shrugging at the government-snooping news. It was headlined, “Why I Just Don’t Give a S**t About PRISM (Or Any Other Spying).” (PRISM is the name of the NSA data-gathering program.)

Greg Plageman – an executive producer of the CBS show “Person of Interest,” in which two outside-the-system characters use the surveillance state as a way to stop crime – finds that lack of concern troubling. (Though, he admits with a chuckle, the scandal has provided great fodder for future story lines.)

“I think the question becomes, Do people care?” he asks. “There’s a measure of indifference here.” Plageman thinks people so love the conveniences of modern digital life, and believe their own online existences are so trivial, that they don’t see much of a downside to being spied on.

The rejoinder to this has generally gone to the other extreme. In response to Wagner’s post, one commenter shot back with the famous verse attributed to Martin Niemoller, the famous Nazi-era German pastor, about not speaking up in the face of tyranny – the one that concludes, “Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Neither extreme is necessary, say experts. You can exert some control over your online life by taking simple steps such as thinking before you post, doing regular cookie deletions, password changes and antiviral runs, and making sure you’ve got your social-media privacy settings in order. And remember: There’s more to life than being online.

As technology theorist danah boyd (who, like e.e. cummings, spells her name in lower-case letters) points out, we’re always interacting with various realms: the state, the individual, the collective and the corporation. Even if we try to opt out – go “off the grid,” so to speak – we still have identities formed by what others know about us.

“It’s not just what you give away, it’s what you give off,” boyd says. “If you decide you want to opt out of Facebook, that’s all fine and well. But most likely, your friends have given Facebook pictures of you – they’ve done a lot of different things to build a model of someone who’s not even there.”

Or, as Sieberg puts it, “It’s worth remembering that our activity online isn’t in a vacuum. How people – friends, employers, colleagues – perceive us can be the sum total of our Internet behavior.”

Opinion: Your biggest secrets are up for grabs

Coding secrets

Maybe we can draw some lessons from the demographic group that’s most socially engaged: teenagers.

A recent Pew study indicates that though teenagers are sharing more of themselves than ever, they’re also using code to hide that information from others. That concept meshes with boyd’s field work, she observes.

In one of the cases she studied, a teen who had recently broken up with her boyfriend was worried her mother would overreact to her sadness and believe her suicidal. So instead of posting a “woe-is-me” message – from which her mother would jump to conclusions – she went the opposite tack and posted the song lyrics from Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Her friends got the message right away.

“In the decade I’ve been watching teenagers, I’ve watched them get more and more sophisticated in encoding meaning,” boyd says.

OK, the pessimists say, but codes can be cracked. And yes, there’s always a place for wariness. “Person of Interest’s” Plageman is less concerned with the surveillance state per se and more with how long the government will hold on to information. Sieberg urges parents to talk to their children about being smart online.

But there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle once it’s started sharing memes on Facebook. If you must be a Web celebrity, at least do so with self-awareness, experts say.

“Clearly we live in special times,” says Vaynerchuk, who nonetheless remains optimistic that we’ll sort out these issues.

“I will always take the bad 1% with the good 99%,” he says.