Leading Women connects you to extraordinary women of our time. Each week, we profile women at the top of their field, exploring their careers, lives and ideas.

Story highlights

Bletchley Park was the home of British code-breaking during World War II

The National Museum of Computing based at the Bletchley estate launched a new exhibit on women in computing

Bletchley's fascinating history only became public several decades after the war ended

Women made up majority of the 10,000 people who worked at secret code-breaking operation

“This is Norway checker,” echoed the voice through the scrambler. “I have a good stop for you in Stavanger.”

Nobody on the outside world could have known what she meant.

But inside Bletchley Park, a World War II code-breaking enclave in the English countryside of Buckinghamshire, 18-year-old Ruth Bourne had discovered a vital piece of intelligence.

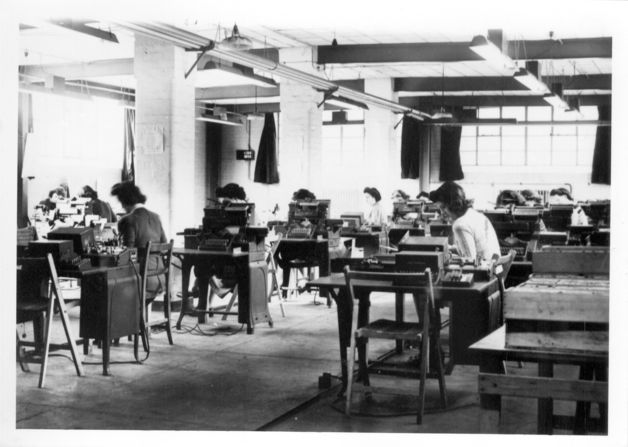

Working alongside thousands of other women to decipher encoded German signals sent between Nazi generals, Bourne’s discovery meant passing on the information to her superiors to assess whether this was another piece of the decryption puzzle.

Read more: Code-breaking Enigma machine goes under the hammer

With every room named after a country that had been toppled by the Nazis, and each machine christened as one of its towns, Bletchley Park’s simple yet effective checking system proved crucial in the defeat of Hitler’s regime.

A culture of secrecy

Far from being a group of experienced decoders, however, the estate’s recruits mainly consisted of young teenage military personnel, a smattering of crossword whizzes who had been able to complete The Daily Telegraph’s puzzle in less than 12 minutes, and numerous 18-year-old girls plucked from their quiet home towns.

“It was the middle of the war when I received a call saying I was to go into war work to support Britain’s efforts from home,” explains 88-year-old Margaret Bullen, a machine wire operator who served from 1942 until the end of the war.

“A letter from the Foreign Office then arrived saying I had an interview – but I had no idea what it was for, and two weeks later, I was told I’d be off to Bletchley.”

Read more: Enigma machine sells for world record price

“Before starting work we were told to sign the Official Secrets Act, which was a rather frightening experience for someone as young and naive as I was,” says 90-year-old Becky Webb, who joined the war effort at age 18 in 1941. “I had no idea how I’d comply with it!”

But compliance was the only option, making these three young women – Webb, Bullen and Bourne – fierce guards of the country’s anonymous decoding history for several decades.

Indeed, it wasn’t until some thirty years later that Bletchley’s long maintained shroud of secrecy began to lift, after the publication of “The Ultra Secret” – a tell all book from former RAF officer Frederick W. Winterbotham, who later became an Ultra supervisor.

The 1974 expose revealed how Ultra intelligence had been used to intercept communication behind enemy lines and disseminate vital information to Britain and its allies. Though Winterbotham was accused of embellishing and aggrandizing his role in the tale, without his account, the real story of what went on inside the UK’s code-breaking operation may never have been known.

Read more: 70-year-old coded war message found attached to pigeon

“It sounds strange that we knew so little about what was going on, but that was how it was,” reflects Bullen.

“I was sent to live with a couple who were ordered to take me in because of the war. They never once asked me what I was doing there–nobody did–not even the local village workers who’d serve us coffee at the café on our lunch break, in spite of the fact a group of 18-year-olds had suddenly arrived in this little hamlet,” she explains.

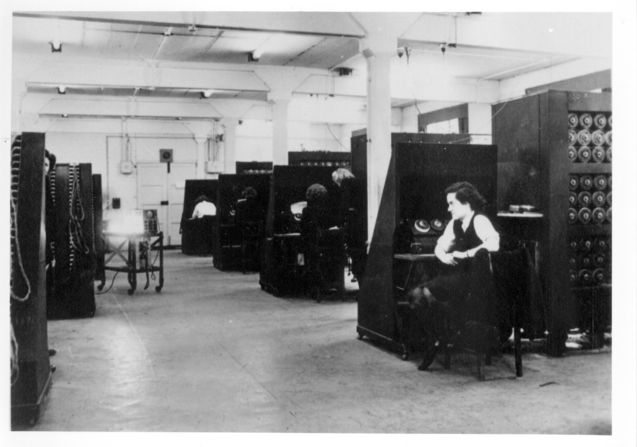

“I only heard the name Colossus–the machine I was working on–some three decades after the war ended, and it wasn’t until I later visited Bletchley Park that I said: ‘this is where I worked, this is what I did!’”

While Winterbotham’s revelations sent shock waves through the secretive decryption community, lifting the lid on what really happened inside the park ensued slowly and sporadically, with the bulk of the information being released in the early 2000s.

“I’m delighted that we can discuss our time there now that everything has come out, and I give talks on the subject whenever I’m asked,” enthuses Webb. “I’ve given 97 to date!”

Silent heroines

For many of the young women at Bletchley, though, the removal of the clandestine veil came too late, with the majority of workers’ parents having passed away before the decryption effort became public knowledge.

Bourne, an 18-year-old naval recruit who was sent to one of the park’s expansion locations in Eastcote – on the outskirts of London – was one of many who was never able to tell her loved ones about her contribution to the war.

“You led two lives there,” she recalls. “One life was in A Block, where you ate in the canteen, and talked about boyfriends, and getting trains to London, and where to find black nylon stockings.”

“B Block was where we worked, surrounded by high walls, barbed wire and two naval marines guarding the place. If you could make your voice heard over the noise of 12 Turing Bombe machines, that was the only time you would speak about work – but you never would,” she explains. “I never knew what any of my coworkers were doing, and vice versa, and my parents never knew a thing of it.”

Read: Timeline: 50 years of women in space

After the Nazi regime fell in 1945, many of Bletchley’s women returned home, while others stayed involved with the military’s work. Bourne was given work as a wire destroyer: desoldering the many cables that had been painstakingly connected during intelligence operations throughout the war, while Webb was sent to the Pentagon to paraphrase translated Japanese messages for transmission to officials.

“Upon leaving Bletchley, we really had no skills whatsoever,” remembers Bourne. “Apart from how to keep a secret!”

And that secret was very nearly never told, especially after the original estate was due to be knocked down some 23 years ago, with houses and a supermarket planned to be built in its place.

Preserving Bletchley

It was in May of 1991 that Bletchley’s fortunes changed after a small local committee gathered a group of veterans at the park to say a final farewell to the historic location.

Read: Natalie Portman: Science’s unlikely heroine

But the group became determined to turn it into a heritage site after hearing the astounding stories of so many code-breakers, engineers and members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WREN) who worked at the park during the war.

The Bletchley Park Trust was formed the following year, and from then on, regular reunions and exhibitions at the estate have enabled its former workers and inhabitants to share stories that were on the precipice of being lost forever.

Winterbotham’s book might have been the first time that story of the World War II code-breakers entered the realm of popular culture, but it certainly wasn’t the last, with TV drama “The Bletchley Circle” proving popular in both the UK and United States earlier this year.

With a second series on its way, and exhibitions at the Trust attracting visitors from around the globe, the world’s fascination with the once elusive Bletchley Park shows no sign of slowing.

The culture of secrecy that once threatened Bletchley from being all but erased from the history books has well and truly ended.

The National Museum Of Computing at Bletchley Park in Milton Keynes, UK unveils its “Women in computing” exhibit.