Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post.

Story highlights

Gene Seymour: Super Bowl points up how NFL's money machine mars joy of game

He says that and coverup of players' long-term injury make him ambivalent about football

Some question whether it's moral to support NFL, especially its overbearing corporate culture

Seymour: Can we not simply enjoy football? Big Business has overpowered the game

As far as I’m concerned, John Matuszak said everything there is to say about professional football back in 1979 when he was playing the role of a bent lineman in “North Dallas Forty.”

Matuszak, or “Tooz” as players and fans knew him, was something of a renegade individualist in the National Football League and the movie’s script gave him the opportunity to unleash a rebel yell: Embittered by his team’s tough loss, and by an assistant coach’s lame scolding, his character goes off on the coach, shouting at one point, “Every time I call it a game, you call it a business. Every time I call it a business, you call it a game.”

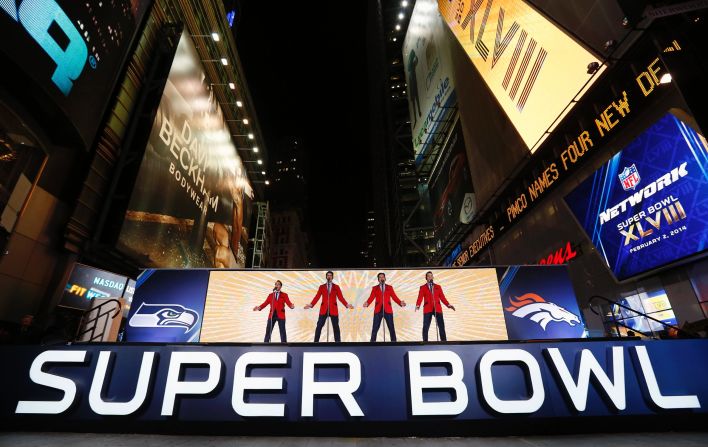

And it’s that very dichotomy that looms even larger during Super Bowl week. The media keep insisting there’s a game being played Sunday night in New Jersey. But all anybody really cares about is the Business – as in, the torrents of revenue being raked in from advertising (have you seen that there are now trailers—for the commercials?), the marketing, the gambling and, of course, the partying that goes on not only in New York and New Jersey in the lead-up to the Ultimate Game, but from sea to shining sea Sunday night.

Players know it, for sure—and it continues to embody my own ambivalence about American tackle football. I get caught up in the game’s drama, its unexpected twists, its ongoing tension between best-laid game plans and the ever-looming potential for their disruptions. I get caught up, too, with the sideline rants, growls, collisions and screw-ups caught at varied speeds by the wizardry of NFL Films.

But while football’s orchestrated aggression and violence may entertain me, my family and friends–and the rest of Living Room America—we’re all newly alive to the physical and mental risks these players are taking. How does one stay passionate about football in the face of the grim, steadily mounting number of cases involving ex-players undergoing physical and mental injury and anguish over the sport’s long-term effects?

In last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, author Steve Almond wondered whether it was immoral to watch and enjoy the Super Bowl while knowing full well that playing the game has caused “catastrophic brain injury … not as a rare and unintended consequence, but as a routine byproduct of how the game is played.” I’ve expressed similar misgivings here about the flood of disclosures about long-term injury and the manner in which the NFL tried at first to either disregard or demean this peril.

It’s not just the dementia, memory loss and other symptoms that cast shadows over the NFL’s gaudy, golden image. This seems the right place to mention that Matuszak, who was so physically imposing as a player that he seemed invincible, died 10 years after “North Dallas Forty” was made. He was only 39 years old and his death was attributed to an overdose of prescription pain medication. Gregg Easterbrook, who publishes the weekly Tuesday Morning Quarterback column for ESPN.com, wrote this week that painkiller abuse “may be pro football’s next scandal.” Over time, watching these players run into each other at top speed while imagining what their minds and lives will be like 20 years afterward could finish me off as a fan.

So could the sheer fatigue of witnessing, year after year, the NFL’s seemingly inexhaustible capacity for inhaling money, which only compounds its overbearing corporate culture. I already have little patience with the game’s ethos as articulated in such bromides as “Doing Whatever It Takes to Win” or that deathless line that the late, exalted Green Bay coach Vince Lombardi appropriated from a John Wayne movie, “Winning isn’t everything, but it’s the only thing,” which even Lombardi, the man for whom the Super Bowl Trophy is named, came to believe was too simplistic. Such platitudes have made tackle football a useable, if not overused metaphor for what it’s like to work, live and, above all, prevail in modern corporate society.

But it’s not just a metaphor. Hard-working men such as my father found release, empathy and satisfaction watching the comparably hard work of his beloved New York Giants for decades. It used to be enough for he and millions of fans over the decades of professional football history to watch skilled craftsmen ply their trade, defy the odds, impose their wills, share their joy and passion. It’d be nice, too, if somewhere in the hype and hysteria, we could all calm down enough to see the Super Bowl in such elemental terms.

But as near as I can tell, it’s the Business that now holds an overpowering edge over the Game. And what’s worse: I can’t tell how much longer the Game itself will hold out.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Gene Seymour.