Editor’s Note: Les Abend is a Boeing 777 captain for a major airline with 29 years of flying experience. He is a senior contributor to Flying magazine, a worldwide publication in print for more than 75 years. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

How can a 650,000 pound airplane disappear for weeks?

Pilot Les Abend says there are gaps in radar, radio communication systems

He says a new system will ensure tracking of planes across the Atlantic

Abend says that system, other modifications, needed to prevent repeat of Flight 370 mytery

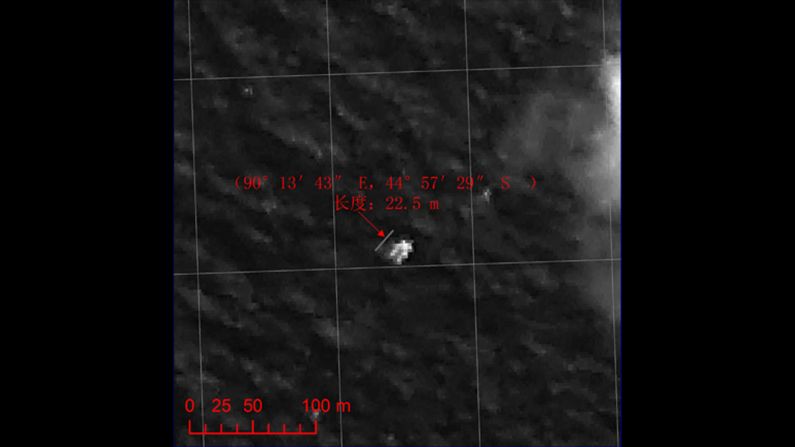

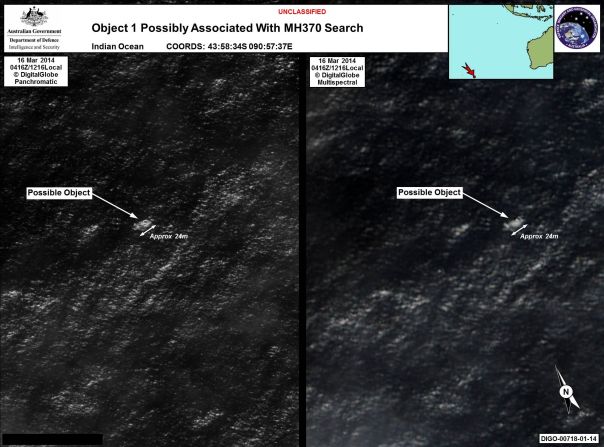

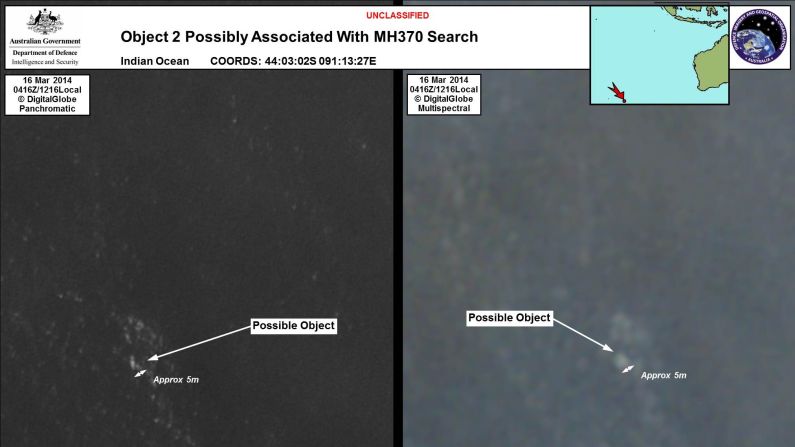

If the pings reported by the Chinese and Australians turn out to be from Malaysia Flight 370’s data recorders, we may be on the road to finding the plane and solving the mystery of its disappearance.

But even if that is the case, we’ll need to resolve a larger issue: Incomprehensible as it might seem to the flying public, it is almost equally perplexing to airline pilots that a 650,000 pound airplane can disappear with barely a trace.

Considering that the 777 is one of the most sophisticated and highly regarded airliners in the world, it doesn’t make sense. Nor does it make sense that in this information overload world of cell phones, Twitter, and Facebook, that communication could break down to such a degree. So, how does one explain this anomaly? More importantly, how does one prevent a Malaysia Flight 370 mystery from happening again?

First, a basic understanding of airspace is required from the standpoint of radar and communication. In most parts of the world, radar is available and operating to track both civilian and military airplanes. Primary radar sends a signal from a ground-based station using that big, screen-like rotating antenna that one sees at the local airport.

The signal bounces back from the airplane and back to the antenna, “painting” a dot on an air traffic controller’s screen. With the use of an on-board transponder, the radar signal “interrogates” the airplane by use of a four-digit discrete code that gives it a specific identity. The code is assigned by air traffic control. In addition to the flight number, or tail number, an airspeed is displayed on the controller’s green scope. All airline flights are issued a discrete code.

For the most part, a transponder code remains the same throughout an entire flight. The code sometimes changes from airspace to airspace or country to country, but it has to be re-assigned by air traffic control and not by the discretion of a pilot, unless an emergency is declared.

Communication with the air traffic control facility that is tracking the transponder code is normally required. Typically, communication is in the form of direct radio contact. With some exceptions, radio contact with air traffic control is always available when a flight begins the landing phase of the trip.

But in remote parts of the world, especially over water, no ground-base radar facility exists. Radar has distance limitations. Radio communication also has distance limitations. As an example, portions of South America have no radar coverage. Portions of that continent have gaps and poor quality radio communication facilities, especially between countries or airspace.

This was mostly likely the situation in the corner of the world flown by Malaysia Flight 370.

It would be understood for pilots and controllers experienced with the route to be aware of such gaps in radar coverage and communication. No alarm bells would be immediately sounded. After a period of time when the flight failed to call at the expected point, the controller would attempt contact on the assigned frequency.

If that attempt failed, the controller would attempt contact on the emergency frequency monitored by all aircraft. And if that contact was unsuccessful, the controller would use an airplane near the lost flight’s route as a “relay.” This was alleged to have been done through a flight bound for Narita, Japan. The Narita airplane was approximately 30 minutes ahead of Malaysia Flight 370. The pilots indicated that all they received was an unintelligible reply that they couldn’t attribute to Malaysia Flight 370. The result would not have been untypical considering the distance between airplanes. So, now what?

Pilot: Why Flight 370 may never be found

Well, those of you who have been following the story have heard about the ACARS, the automatic communication and reporting system, on board. Yes, the ACARS should have functioned by using either a dedicated radio frequency or a satellite signal to automatically send position data, among other parameters.

The amount of parameters is dictated by the program subscribed to by the airline. For whatever reason, the unit failed, only performing a “handshake” with the satellite. But another system on board could have saved the day, or at least more accurately pinpointed the position for air traffic control. What is the system?

It’s called, ADS-B, short for automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast. In contrast to radar, the airplane sends its own signal to the satellite, which returns the signal to a ground base station, which transforms it to a target display on a controller’s screen. This system is already in use, and will be completely mandated for all of the North Atlantic tracks between North America and Europe.

Even over the desolation of the North Atlantic, an airplane can never be lost. ADS-B will be required for all airplanes operating in the continental United States by 2020.

The flaw is that each air traffic control facility has to be equipped with the ADS-B system for it to function. And the flaw in ACARS is that the system will not report if it malfunctions. To the best of my knowledge, the ACARS system is not connected directly to the battery, which would maintain its operation during a major electrical failure.

What’s the difference between ACARS and ADS-B? Simply stated, ADS-B is an air traffic control function. ACARS is an airline company function, offering a variety of optional downloadable data parameters for dispatch and maintenance purposes.

So, do we require these systems to prevent another airplane disappearance? My view is yes.

Although many countries are adapting an ADS-B system, mandating it all over the globe would be a difficult process. Most airlines have an ACARS system but it would require modifications to re-wire into an emergency (electrical) bus. And it would require airlines to subscribe to the higher level of data downloading.

The technology for streaming aircraft data via a satellite has been discussed in the wake of this tragedy, but it appears bandwidth would have to be increased. The issue of data security would also have to be addressed.

Many folks have suggested modifications to the black boxes. But the black boxes are after-the-fact technology. Their use is forensic. Let’s fix the problem before it happens. The objective of a new regulation should be to prevent a similar situation from occurring again, not to find easier methods to pick up the pieces.

And in this circumstance, the objective is to never let an airplane disappear again.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.