Editor’s Note: Neal Gabler is the author of “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.” He is working on a biography of Edward Kennedy.

Story highlights

Neal Gabler: Rooney was very unusual in Hollywood. A child actor with enduring success

He says he had quality unlike male stars of Golden Age: not powerful, but plucky, vulnerable

He conquered through energy, determination, not strength. His image was hopeful, sincere

Gabler: He expressed how Americans wanted to see themselves

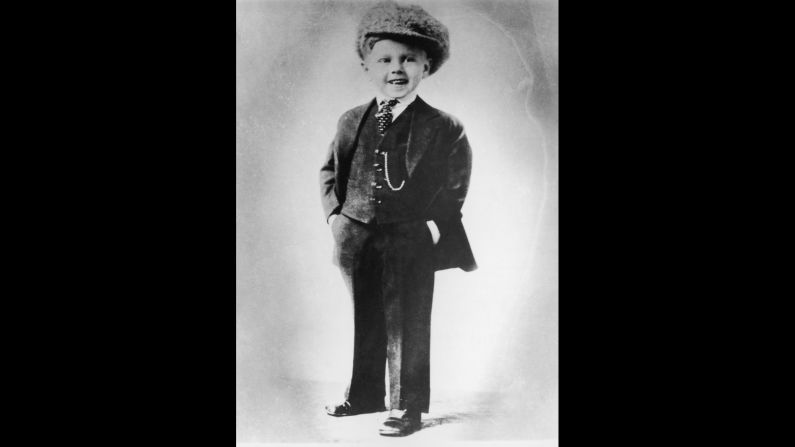

Mickey Rooney, who died Sunday at 93, may have been the most unusual major star in the history of Hollywood. Why? For one thing, at the peak of his fame, he was only a youth. In the late 1930s into the 1940s when he topped the Hollywood box office, earning the then huge sum of $150,000 a year, there were few child actors with his clout. In fact, unlike today, there weren’t many child actors at all. Only Shirley Temple and Deanna Durbin could begin to rival him.

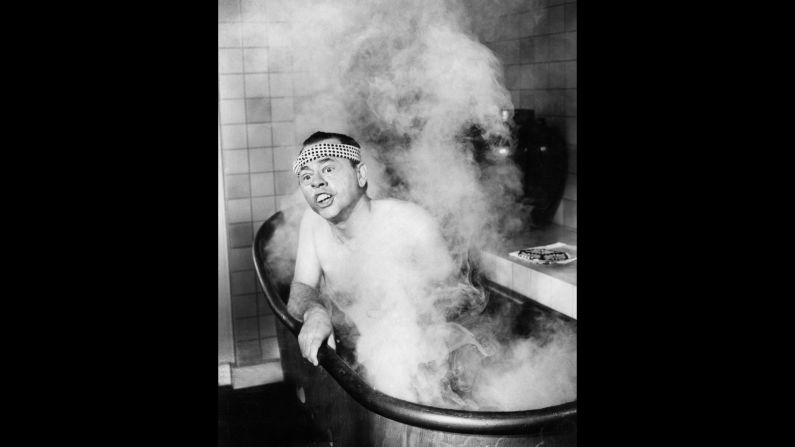

Then there was his size, even into adulthood. There were other diminutive stars in Hollywood’s Golden Age, such as Jimmy Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, Paul Muni, Humphrey Bogart, but no one as pint-sized as Rooney, who topped out at just 5-foot-2. We like our stars to be outsized. Rooney was definitely undersized.

But Rooney had something else that no other star had. Male stars – then as now – were largely figures of power: not just Cagney and Bogart, but Clark Gable, Errol Flynn, even Spencer Tracy. Moviegoers were attracted to their ability to dominate, to bend the world to their will. Rooney didn’t exude power. He exuded pluck.

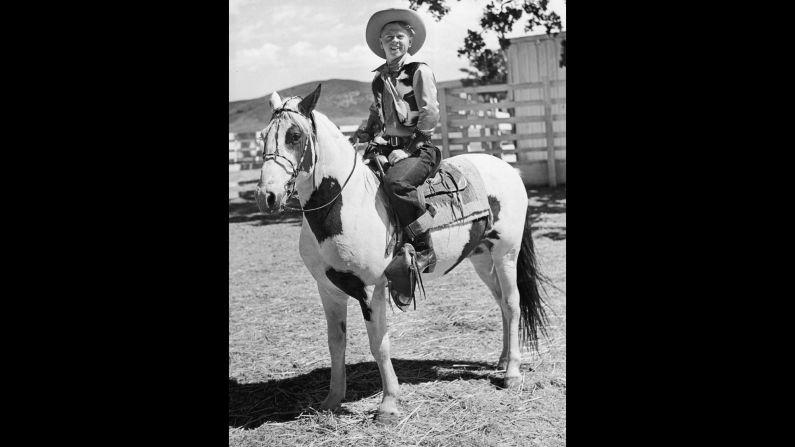

Rooney never played the conventional hero vanquishing forces of evil. He was best known as Andy Hardy in a series of films at MGM: the quintessential young man in the quintessential small town with the quintessential family and honoring quintessential American values. About the only things he vanquished in these movies were his own doubts or his own lovesickness or his own moral quandaries. Andy was eager, loving, decent, thoughtful – not the qualities we ascribe to movie heroes but the very qualities Americans, particularly as they emerged from the Great Depression – liked to ascribe to themselves.

He didn’t conquer through strength. He succeeded through sheer energy. “Let’s put on a show,” the joking line attributed to Rooney in those Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland pictures, expressed what Rooney was about: not American muscle, but American determination.

And if Rooney didn’t convey power, he didn’t convey manliness either. (Hell, he wasn’t even a grown man in his heyday.) The great male stars of his time didn’t cry. They didn’t even wince. They were stoics patrolling America’s mean streets. Only Jimmy Stewart among them even seemed to have a tender side. But Rooney was no stoic. He did cry. He was open and vulnerable and wounded and occasionally scared.

Think of the last scene in “The Devil Is a Sissy” where he stares into the night after his prisoner father is executed. He couldn’t stare down the world the way the other male stars did. He could only stare into it, often with wonder and pain. After all, he was still a boy, he could expose his heart. He could be hurt.

And there was one more thing about Rooney that made him an unusual star in the Hollywood constellation. Almost every great star then, male and female, was a cynic. They were hard-boiled, had learned to survive life, but lived without illusions. Think of Bogart in “The Maltese Falcon” or “The Big Sleep” or Bette Davis in just about any of her pictures. Rooney, again partly because of his youth, was devoid of that cynicism.

He was hopeful, idealistic, utterly sincere. In a movie world of doubt, Rooney alone was a true believer. In these three ways – pluck and heart and idealism – Rooney may have come closer to the American ethos in Depression-era America than any other star. He was loved not because he expressed what we could only hope to be, but because he expressed what we liked to think we actually were.

Take Rooney in what is arguably his best role, as Homer Macauley in Clarence Brown’s screen version of William Saroyan’s World War II novel, “The Human Comedy,” from 1943. Homer’s job is to deliver telegrams, including those informing families of their sons’ death in battle – more Rooney sadness. This was MGM head Louis B. Mayer’s favorite film because it captured the idealized way he viewed America, with Rooney as the idealized American boy–though the director Billy Wilder once recalled to me a time he found Mayer throttling Rooney on the lot after some transgression and yelling, “You’re Andy Hardy! You’re America!”

That Rooney was. His death is a reminder of an earlier time when Americans had a more innocent vision of themselves. Rooney’s persona may not have worn well over time – it was a young man’s persona – but in the ’30s and ‘40s he was the personification of that innocence, and a vestige of it has passed with him.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.