Editor’s Note: Mark O’Mara is a CNN legal analyst. He is a criminal defense attorney who frequently writes and speaks about issues related to race, guns and self-defense in the context of the American criminal justice system. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

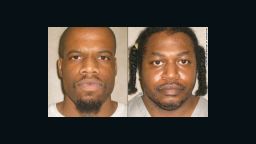

Mark O'Mara acknowledges if anyone deserved death penalty, Clayton Lockett did

O'Mara: But execution is a 19th-century relic, and we still can't do it properly

He asks how many innocent inmates have been killed?

O'Mara: It doesn't deter crime, and victims' families often left feeling no relief

If anyone deserved the death penalty, it was Clayton Lockett. He committed a series of vile acts that we as a civilization would condemn under any circumstances.

In August 2000, a jury in Oklahoma found Lockett guilty of first-degree murder, rape, forcible oral sodomy, kidnapping and a bevy of other charges – 19 in all. They stemmed from a robbery-gone-wrong in which victims were tied up at gunpoint; one young woman was raped multiple times, and another, who had just graduated from high school, was shot and buried alive in a ditch.

On Tuesday night, Lockett was scheduled to die by lethal injection – the preferred means for executing criminals in states that allow for the death penalty.

During lethal injections, subjects are given a chemical cocktail designed to put them to sleep, render paralysis and then stop the heart. One problem for death-penalty states, such as my state of Florida, is the chemicals used for lethal injection are hard to come by, partly because some companies who produce the chemicals refuse to sell them for the purposes of executions.

So in the case of Lockett, the state of Oklahoma tested a new combination of chemicals. Instead of putting Lockett to sleep and stopping his heart, the administration of the lethal injection caused his vein to burst, and about 45 minutes later, he died of a heart attack. It’s been dubbed a “botched execution,” and Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin stayed another execution scheduled for Tuesday evening pending an investigation.

This is an absurd problem for states to wrestle with – this notion of how to kill someone properly. Like I said, if anyone deserved the death penalty, it was Lockett, but the real debate is whether we need to be in the business of trying to find the least cruel and least unusual way to kill anyone voluntarily. It seems clear that the death penalty is a 19th-century relic, and our ridiculous struggle to figure out how to do it properly in the 21st century is a signal that perhaps we should join the rest of the civilized Western world in abolishing executions.

Even Russia hasn’t had an execution since 1999, and I wouldn’t exactly call Vladimir Putin soft on crime.

But please understand that I am not some left-wing, dyed-in-the-wool liberal who simply believes all criminal behavior is the fault of a system that fosters deviance. Not at all. I believe that if you take somebody’s life with premeditation, and if a jury, after hearing all of the evidence properly presented by competent counsel, finds you guilty, then you should die – but in prison, at the end of a life sentence.

My objection to the death penalty is pragmatic. It’s ineffective as a deterrent, and it is an extraordinary burden on our justice system.

For a punishment to offer an effective deterrence, it has to be applied swiftly to maintain the logical cause and effect relationship with the crime, that this is a consequence. But we simply cannot, and should not, act quickly. The extended period required to ensure that the death penalty is appropriate – that all options and appeals have been exhausted before resorting to the ultimate punishment – is an essential safeguard in a civilized society. In Lockett’s case, this process took nearly 14 years.

Even with this long process of appeals, our system is far from perfect. Innocence projects around the country have saved 144 death-row inmates since 1973 by presenting new evidence that has proven them not guilty. Think of how many innocent people we have executed, when the number should be zero. We should all be shocked and appalled. Since we know innocent people sometimes get convicted based upon bad identification, faulty witnesses, improper police activities and incompetent counsel, can’t we at least agree to avoid killing somebody when we know we have an imperfect system?

And the burden of the appeals process on the criminal justice system is huge. A recent report from Amnesty International shows the average cost to carry a death penalty case from prosecution to execution is three to 10 times more than a case with a life sentence. Very often, a life sentence costs the state less than $1 million. Some death penalty cases have cost more than $10 million. The excruciatingly long, and necessary, appeals process in death penalty cases cost taxpayers millions for each case, and it draws resources away from other important prosecutions. Is it worth the price?

It would be worth the price, if that was what it took to get justice. But is the death penalty justice? Or is it retribution? Often in a death penalty case, members of the victim’s family are the strongest advocates for a death sentence. They say they want justice for their slain loved one, but what they often truly want is retribution. This is both understandable and acceptable. An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. But it’s never that simple.

I’ve tried death penalty cases, and I’ve been lucky: None of my clients has ever been sent to death row. But I know many good lawyers who haven’t been so lucky. You may be surprised to know that in many death penalty cases, which last for years, defense lawyers get to know victims’ families. The families of homicide victims, after an execution, often don’t feel the long sought-after sense of relief they expected. Often, they are left, instead, with unresolved emptiness. Two lives are lost when a murder is committed, and two families are irrevocably altered. We should feel the pain as well, and spend more time, effort and money on those who are affected. We should not spend ever-dwindling resources figuring out ways to kill.

The death penalty is flawed in every conceivable way, and it should be abolished.