Story highlights

CNN's Steven Jiang recalls his time as a student in Shanghai during the Tiananmen crackdown

Jiang says his Chinese friends express surprise, indifference as CNN marks 25th anniversary

Chinese government has made strenuous efforts to erase the period from national consciousness

Officials continue to suppress all mention of events in 1989 by censorship of media, Internet

In between sipping drinks and reminiscing about bygone times at a recent reunion of my high school class, old friends curious about foreign news media’s coverage on China asked what stories I was working on.

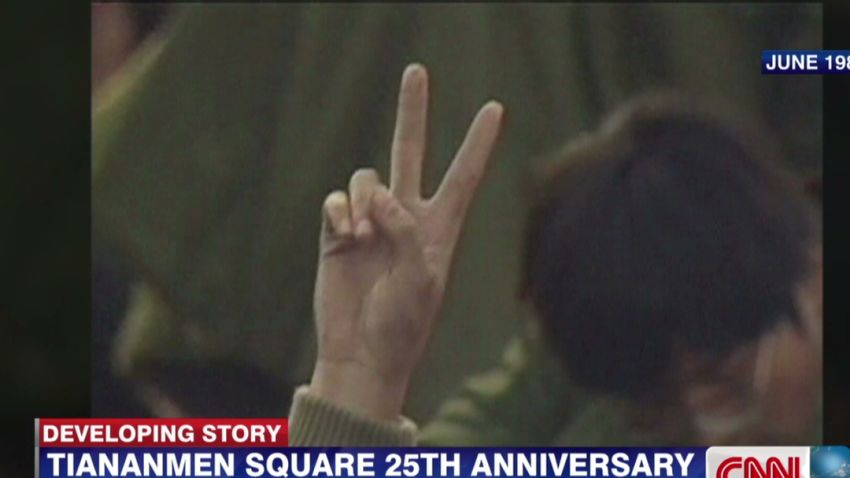

When I mentioned the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown – which killed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people – as a major topic of interest in the coming days, the reaction was almost always surprise followed by indifference.

“Really? Who still cares about that?”

Most of my former classmates who graduated from an elite Shanghai high school in 1994 are established both professionally and personally. Now in their late 30s, they are doctors, bankers, engineers and businessmen living comfortably and raising their young children in China’s largest city.

TIMELINE: The Tiananmen Square crackdown

When nudged, some classmates recalled the excitement we all felt as fresh-faced 8th graders witnessing history unfolding in front of our eyes back in 1989.

Mass demonstrations started in Beijing in April that year as university students gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn the death of an ousted liberal Communist Party leader. By mid-May, the movement had become a nationwide phenomenon as people – students, workers and intellectuals, united by their grievances against inflation and corruption – took to the streets to demand political reform.

Our high school sits on a busy commercial street linking the city center and a university district in Shanghai. Almost every day that late spring, from our third-floor classroom, we could hear the chanting and cheering as demonstrators marched past our campus.

‘Freedom’

We would rush downstairs or to the windows during breaks to watch the demonstrations. A sea of red flags and banners was a memorable scene of people power for those of us born after Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution. It was also thrilling to hear shouts of “democracy” and “freedom” reverberating in the air, as those words had largely been taught as phony Western concepts in political science classes.

In the end our political science teacher turned out to be right after all. Every time when she sensed our diverted attention, she would remind us to focus on our textbook instead of the protests outside: “This will be over shortly and nothing good will come of it.”

A few weeks later on June 4, soldiers in Beijing opened fire on civilians to clear Tiananmen Square of protesters. Several days after that, Shanghai authorities removed roadblocks set up by local demonstrators to disrupt traffic in protest at the brutal military suppression in the capital.

When the dust settled and a new Communist leadership was installed in Beijing, the same political science teacher returned to give us the Party’s version of the events.

“Counter-revolutionary riot,” was the official verdict on the pro-democracy movement she wrote on the blackboard, emphasizing that the lesson was mandatory and a test would be given.

Tank man

We were required to watch a video produced by state broadcaster CCTV, which contained the iconic image of the “tank man” – an unknown protester standing in front of a column of tanks to stop their advancement.

GALLERY: Behind the ‘tank man’ image

“He was like a mantis trying to obstruct a chariot.” I still remember this Chinese idiom used by the announcer. “If not for the restraint of our military, he would have been obliterated.”

Along with political indoctrination, other aspects of life seemed to have returned to normal rather quickly – at least in the eyes of teenagers. By the time I left China for the United States in 1993, the Tiananmen protests had become a distant memory in my mind thanks to the government’s strenuous effort to erase the events from national consciousness shortly after the bloody crackdown.

While I later found out more about what happened in 1989 and to those involved in the movement by reading eyewitness accounts, foreign news reports and academic papers, most of my former classmates staying behind in China did not enjoy such access. What they – and the generations after them – have enjoyed are the fruits of China’s breakneck economic development that started in the early 1990s.

“The Communist Party was forced to strike a deal with the Chinese people in 1992,” said Wu’erkaixi, a student leader of the pro-democracy movement who fled China after the military suppression and has lived in exile ever since. “The Party gave them the right to make money in exchange for political cooperation – the deal worked.”

The Taipei-based activist, who remains the second most wanted man in China for his role in the Tiananmen protests, says he is not surprised by the Chinese leadership’s continued refusal to re-assess the movement, even though its official description has been watered down to “political disturbance between the spring and summer of 1989.”

“The new ruling elite post-1989 has been a mixture of princelings and technocrats,” he said, referring to descendants of Mao’s peers and officials with a technical background. “They have formed an alliance to write laws that benefit them and protect their entrenched interests above anything else – so they have little tolerance to any challenge to the status quo.”

Annual crackdown

Every year around June 4, the Chinese government rounds up political dissidents, human rights advocates and families of the crackdown victims to prevent them from gathering or speaking to mark the occasion.

Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, himself a princeling, the authorities struck earlier and harder this year, detaining activists – including prominent lawyer Pu Zhiqiang – for attending on low-key seminar on the Tiananmen protests. Veteran journalist Gao Yu, another well-known voice on the topic, was taken into custody for allegedly leaking state secrets even before the meeting. Leading human rights activist Hu Jia, who is organizing an online campaign to commemorate the 1989 movement, has been under house arrest since late February.

Tiananmen Square, a major tourist attraction, remains off limits to foreign news outlets, especially around June 4. Soldiers, police and state security agents flood the square during the anniversary period, ready to halt even the slightest sign of on-site reporting.

With references to the protests long banned in textbooks and print media, the authorities are now busy blocking Google services and scrubbing allusions to the taboo subject in cyberspace, ordering social media to block keywords as subtle as “this day,” “25 years” and “between spring and summer.”

The ever-stricter censorship may have caused many young Chinese – people in their 20s and early 30s – to appear oblivious of the 1989 movement as my colleagues discovered on the streets of Beijing.

“I’m not worried about this thanks to the Internet,” Wu’erkaixi said. “Even the small percentage of people who do know is too big for the government to cover it up.”

“People will eventually understand that many issues today stem from social problems that weren’t resolved in 1989,” said Hu Jia, the activist under house arrest. “In a tyranny, they are deprived of a series of rights – land grabs, forced home demolitions, educational inequality and environmental pollution are all along the same line.”

Measured progress

For the most part, though, many young professionals and entrepreneurs – while complaining about a widening income gap and rampant official corruption amid a slowing economy – have told me that they believe in measured progress instead of revolutions for a vast country like China.

“You can call them pragmatic and materialistic, but they are also individualistic – and individualism has been the perfect incubation for the idea of equality and freedom,” Wu’erkaixi offered. “It has happened in the West – and the younger generations in China will have their glory tune.”

But it’s unlikely to be “Nothing to My Name,” a rock song by Chinese superstar Cui Jian about the dispossessed youth that became the unofficial anthem for Tiananmen Square protesters a quarter century ago.