Story highlights

Organization: 140,000 Cambodian migrant workers leave Thailand

Workers cite fears and anxieties of a potential crackdown

Thailand officials say there is no crackdown on migrant workers

Fearful of a crackdown on undocumented workers, thousands of Cambodian migrants clutching children and towing their possessions in sacks and plastic bags, milled into a train station.

They crammed inside in an orderly fashion– mostly nervous and solemn – as they waited for the train that will take them back to Cambodia.

“They told me the Thai military would arrest us, and they would shoot,” said Bo Sin, a Cambodian construction worker who was among those departing from the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet.

When asked where he got this information, Bo Sin replied, “It could be a rumor, people are passing along this information.”

Many of the Cambodian workers echoed Bo Sin’s fears. They say they’re leaving because of talk of arrest and persecution – unsubstantiated allegations that the Thai junta vehemently denies.

But it has not stemmed the tide of Cambodian workers heading to the borders. About 140,000 migrant workers have fled Thailand causing bottleneck congestion at the border, said Joe Lowry, spokesman for the International Organization for Migration.

“I feel really afraid, and my mother also called me to return home,” said Ban Sue, a Cambodian cook who had worked at a Bangkok restaurant.

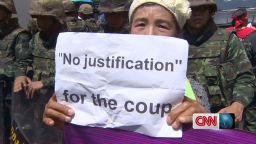

Thailand has been under the control of the military since a coup in late May. Although tackling illegal migration has been one of the junta’s priorities, unease over the issue and the sudden change in government may have fueled the migrant workers’ concerns.

Thai officials say there is no crackdown on undocumented workers and that it has been spurred by “groundless news reports based on rumors.”

Neither the junta nor local authorities have issued orders concerning migrant workers, said Sek Wannamethee, spokesman of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand in a press release.

“The rumor which was spread by unknown sources has caused panic among both Cambodian workers as well as Thai employers,” he said. “Consequently, a number of Cambodian illegal workers have reported themselves to the Thai authorities to be repatriated voluntarily to Cambodia.”

There has been no use of force or killings, Sek Wannamethee said.

It remains unclear where talk of a clampdown originated.

The International Organization of Migration, an intergovernmental group, estimates there are 150,000 Cambodian undocumented migrants in Thailand with the majority of them working in construction or agriculture.

Thailand is believed to have about two million documented foreign migrant workers from countries including Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos who work in low-paying jobs that Thais are unwilling to do, according to a news service for the U.N. Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Foreign workers are often vulnerable to police harassment and exploitation, advocates say.

“Many of these people are severely economically disadvantaged and have spent all their savings, if they had any, to get this far,” said Brett Dickson, IOM’s team leader in Poi Pet, Cambodia, in a news release.

In recent decades, relations between Cambodia and Thailand have been dogged by border issues, tensions over an area surrounding the ancient Preah Vihear temple, and the 2003 burning of the Thai embassy in Phnom Penh by rioters.

Slaves at sea: Report into Thai fishing industry finds abuse of migrant workers