Story highlights

There may be the equivalent of 45 billion barrels of oil under Kurdish land

U.S. opposes sales as a destabilizing factor

The Kurdish government needs cash quickly

Iraq is "falling apart," the region's President says

For sale: One million barrels of crude oil. Attractive discount offered. Currently sitting off Moroccan coast.

That’s what the Iraqi Kurds are offering potential buyers, much to the fury of the government in Baghdad. It amounts to a declaration of economic independence, fraying the already tattered ties holding Iraq together.

Here’s how it works:

The Kurdish Regional Government, or KRG, deals with oil exploration companies independent of the central government.

Exxon Mobil, Chevron and Total are among the companies working in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The crude produced there goes through a pipeline to the Turkish port of Ceyhan in the Mediterranean. Then it’s loaded onto tankers and floats about until it finds a buyer.

The proceeds are held in a Turkish bank; the Kurds say they will take 17% and the Iraqi government is entitled to the rest.

Who are the Iraqi Kurds?

Along with the Shiite Arabs and the Sunni Arabs, the Kurds are one of the three dominant groups in the fractious and diverse nation of Iraq.

While most Kurds are Sunnis and a minority are Shiite, they identify first as an ethnic group. They are distinct from Arabs and speak an Iranian language.

The Kurdish population numbers 15% to 20% of Iraq, which has a population of 32,585,000, according to an estimate from the CIA World Factbook. There are also large Kurdish populations in the neighboring countries of Iran, Syria and Turkey, with varying levels of independence aspirations.

The KRG rules an autonomous region with its own Cabinet, parliament, president and military forces. The region consists of three provinces In Iraq’s north: Irbil, Sulaimaniya, and Duhuk.

The Kurds had been oppressed by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein government, but the area has avoided much of the country’s warfare since Hussein’s overthrow in 2003.

Today, Iraqi Kurdistan is regarded as a relatively stable and economically booming Middle East success story, thanks to its oil clout.

Scaling up

The KRG began exporting small amounts of crude oil in trucks last year, but the pipeline to Ceyhan gives it the opportunity to scale up.

Industry sources say more than 100,000 barrels are flowing through the pipeline every day, and more than 2 million barrels are already stored at Ceyhan.

Altogether, there may be the equivalent of 45 billion barrels of oil under Kurdish land in Iraq, according to the KRG.

Aligning with Israel

The most recent buyer appears to be Israeli.

Late Friday, the SCF Altai docked at the port of Ashkelon, having taken on a load of Kurdish crude from another tanker in the Mediterranean a week ago.

Why Israel? It’s not clear who the buyer is, or whether the oil changed hands once or more before finding its final destination.

But the Israelis may see the Kurds as a natural ally in a region where both feel they are threatened minorities.

Problems offloading

Another much larger cargo – said to contain 1 million barrels – has been at sea for more than a month.

According to shipping sources, the United Leadership tanker was at anchor off Casablanca in Morocco late last week, still looking for a buyer. Ship tracking databases had the vessel listed as “For Orders,” meaning its cargo does not yet have a destination.

SEE MAPS: Where ISIS has taken over in Iraq

The United Leadership’s limbo suggests that despite reportedly offering big discounts for its crude, the KRG is having problems offloading it.

Some buyers are worried about Baghdad’s threat to sue anyone who buys Iraqi oil other than through the state company. The Iraqi government has already blacklisted some agents and importers of Kurdish oil, including the Austrian company OMV.

Other buyers

Reuters reported earlier this month that Russian oil company Rosneft had bought a cargo of Kurdish crude for a refinery in Germany that it co-owns.

Forty one thousand tonnes of oil – which had been trucked from Kurdistan to Ceyhan – were carried by the Minerva Antonia tanker to Trieste in Italy and then sent by pipeline to Germany, the agency reported.

Turkey says it regards the sales and the use of a Turkish port as legitimate, but also has political interests at stake in a complex regional picture.

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has developed close ties with the Kurdish leadership in Iraq – partly to dissuade it from making common cause with Turkey’s restive Kurdish minority. Turkey also wants to diversify its sources of energy. It concluded a 50-year deal with the KRG this month (though details of the agreement remain sketchy).

‘Playing with fire’

The Iraqi government has begun legal action against Ankara at the International Court of Arbitration.

Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Hussain al-Shahristani warned Turkey that it was “playing with fire” and “plundering Iraq’s wealth.”

The United States also opposes the Kurdish sales as a further destabilizing factor in a country at risk of breaking apart. Producing or refining companies working in parts of Iraq still under the control of the central government seem to be avoiding involvement with the Kurds’ unilateral action.

Need for cash

But the KRG needs cash – lots of it and quickly – because negotiations with Baghdad over the Kurds’ share of oil revenues have stalled. It has also borrowed heavily.

Its monthly wage bill is more than $700 million – that’s 70% of the entire budget just going on salaries. And now that its peshmerga forces are fully mobilized in protecting Kurdistan from the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, that spending is likely to rise.

According to a recent study by BoA Merrill Lynch, the KRG would need monthly sales from 20 tankers holding a million barrels of oil each to make $340 million.

Fraught with peril

But Denise Natali, senior research fellow at the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University in Washington, believes the sales are fraught with peril.

“The key issue is transparency and risk-free exports,” she told CNN. “If something is legitimate or legal – as both the Kurds and Turkey claim – why then does the sale of Kurdish crude remain shrouded in so much mystery and murkiness, with transfers at sea, and buyers and prices not being identified?”

“Any sales that may eventually occur will still be considered illicit trading by Baghdad; and that will entail litigation and brings with it reputational damage.”

A price

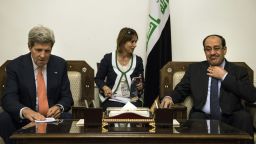

As the government of Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki in Baghdad tries to stave off advances by ISIS, the Kurds are in a strong bargaining position. Their peshmerga forces have been able to repulse ISIS attempts to infiltrate the Kurdish region – and might yet help government forces go on the offensive.

But there will be a price.

Above all, the KRG wants the major city of Kirkuk – which it now occupies and where Kurds, Turkmen and Sunni all live – to be recognized as part of the Kurdish autonomous region.

The KRG’s President, Masoud Barzani, told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour on Monday that Iraq was “falling apart … and it’s obvious that the federal or central government has lost control over everything.”

“And we cannot remain hostages of the unknown,” he added.

CNN EXCLUSIVE: “Time is here for self-determination”

A new confrontation?

Peshmerga forces last week took control of the Kirkuk oilfield, strengthening the Kurds’ hold over Iraq’s northern oilfields. The Kirkuk oilfield is Iraq’s fourth largest but badly in need of investment.

But Natali, who has followed events in Iraq for more than 20 years, says the Kurds’ assertiveness may end up generating a new confrontation.

“Barzani does have leverage over the Maliki government because it is so weak, and the Kurds’ occupation of the Kirkuk fields does strengthen their short-term bargaining position. But such weakness and politically expedient alliances may not last forever,” she says.

“The Maliki government may be replaced by a more inclusive and therefore stronger government in Baghdad, or a Sunni Arab state may emerge on the Kurds’ doorstep that may not be amenable to Kurdish demands.”

Relying on Turkey

The Kurds are also very reliant on Turkey’s goodwill.

“The Iraqi Kurds are increasingly dependent on Turkey as a conduit for their oil and financing,” Natali told CNN, “and the close relationship between Barzani and Erdogan is largely responsible for the current arrangement. But some groups in the Turkish parliament and some Iraqi Kurdish politicians have been very critical of this opaque arrangement,” wary of ruining relations with Baghdad and alienating Washington.

For now, the Turkish and Kurdish governments appear to feel that the retaliation threatened by Baghdad can be ignored.

Turkey’s Energy Ministry said last week it expected another shipment of Kurdish oil to leave Ceyhan soon. According to a ship tracking database, that oil is aboard the 85,000-tonne Greek-registered United Emblem, which left the port at the weekend – destination unknown.

Western-born jihadists rally to ISIS’s fight in Iraq and Syria

Iraqi Kurdish leader: ‘We are facing a new reality and a new Iraq’