Editor’s Note: In high school, David Martinez learned that he is an undocumented immigrant. Under President Barack Obama’s executive order in 2012, Martinez was granted relief from deportation. His story first appeared on CNN iReport. Explore the journey out of the shadows led by undocumented immigrant and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas. CNN Films’ “Documented” airs Sunday, June 29, at 9 p.m.

Story highlights

David Martinez was born in Mexico, and thought he came to the U.S. legally

At 14, his parents revealed he was an undocumented immigrant

He distanced himself from speaking Spanish, playing soccer and anything Mexican

In his 20s he finally learned to embrace his Mexican heritage

When I was just 3 months old, I was smuggled by my aunt into the United States.

I was born in Jerez, Zacatecas, Mexico. Only three months separated me from being a U.S. citizen. Three small months that could have completely changed my life.

Growing up in a town near Los Angeles, which is predominantly Hispanic, I always fit in. I never thought about race until I got to middle school. That’s the first time I remember being called “Huero” and “white boy” because of my light skin and green eyes.

I knew my family was Mexican, but part of me was embarrassed. My parents didn’t speak English, so I avoided having conversations with them in front of my friends. I was “too cool” to be associated with being Hispanic. I was lost in my culture.

Now I know this was the case with lots of my friends – we were all searching to fit in. It’s in part because of the way the American culture has brought us up. There were two classes at my middle school: “Americanized” Hispanics and “beaner” Hispanics. If you were dark-skinned and didn’t speak English well, you were called a “beaner” and a border-hopper. You would be seen as “uncool” or an “outsider.” In gym class, some of the better soccer players were called “beaners.” It was Hispanics being racist toward other Hispanics.

I was one of those people who wanted to be associated with the more “American” kids, so I always went along with it as I entered high school. I tried to be like my friends as much as possible. They were second- or third-generation Mexicans who spoke English at school and hung out with the white kids. I dressed like the Americans who wore skater shoes, baggy pants and Billabong T-shirts. And even though I loved soccer, I thought it was too Mexican, so I played football instead.

Sadly, distancing yourself from your home culture was considered the norm. I fully regret it and wish I never had a part in it.

Share your personal essays with CNN iReport

Freshman year is when I first found out I was undocumented. I was waiting at registration and when the clerk was going through my paperwork, she asked if I knew my Social Security number. I told her I’d get it from my mom later. When I got home, my parents had told me about my “story.” I remember feeling ashamed of myself, that I was one of them, a “beaner.” I mean how could someone like me, someone who looks white, be an undocumented immigrant?

I always thought undocumented immigrants were working the farms and not speaking English. It’s bad to say, but that was my vision of what an undocumented immigrant was. I always felt like I was too good to be an undocumented immigrant. I spoke perfect English. I got good grades in high school. I played sports. I was your typical American kid.

I couldn’t help but wonder: Why is that one piece of paper stopping me from saying I’m an American?

Watch 'Documented'

Watch ‘Documented’

From that point on, my life changed. I realized that I would not be getting my driver’s license at 16. I would not be getting a summer job to make money. Throughout high school, I was always careful about what I said in my circle of friends. When my friends would talk about going on vacations to other countries, I would feel so left out. I hated hearing them because it would bring me down. I wished that I had been born here. I wish I had been a U.S. citizen.

But you can either dwell on it or deal with it. I chose the latter. At 17, I got my first job working at a video store. It helped me feel more “normal” and more “American,” even though I still couldn’t legally drive. After I graduated, I started driving without a license. I had no choice; I had to get to work and school. When most people my age were excited to drive, I felt the opposite. Every time I was behind the wheel, I had a constant fear of being pulled over. Yes there was some excitement, but that quickly faded when I realized the risks I ran. Being pulled over meant a ticket, my car being towed, and money to fix it all. When I was 21, I got into a minor accident where I made a small dent on an older man’s car. When I pulled over, I just remember wanting to disappear or die. My heart sank and I was scared out of my mind. I called my dad, who came over quickly with my uncle. As I waited, the man insulted me. When he learned I had no license he flipped, cursing me and calling me every name in the book. After that accident I was even more cautious when I drove.

Vargas: Undocumented and hiding in plain sight

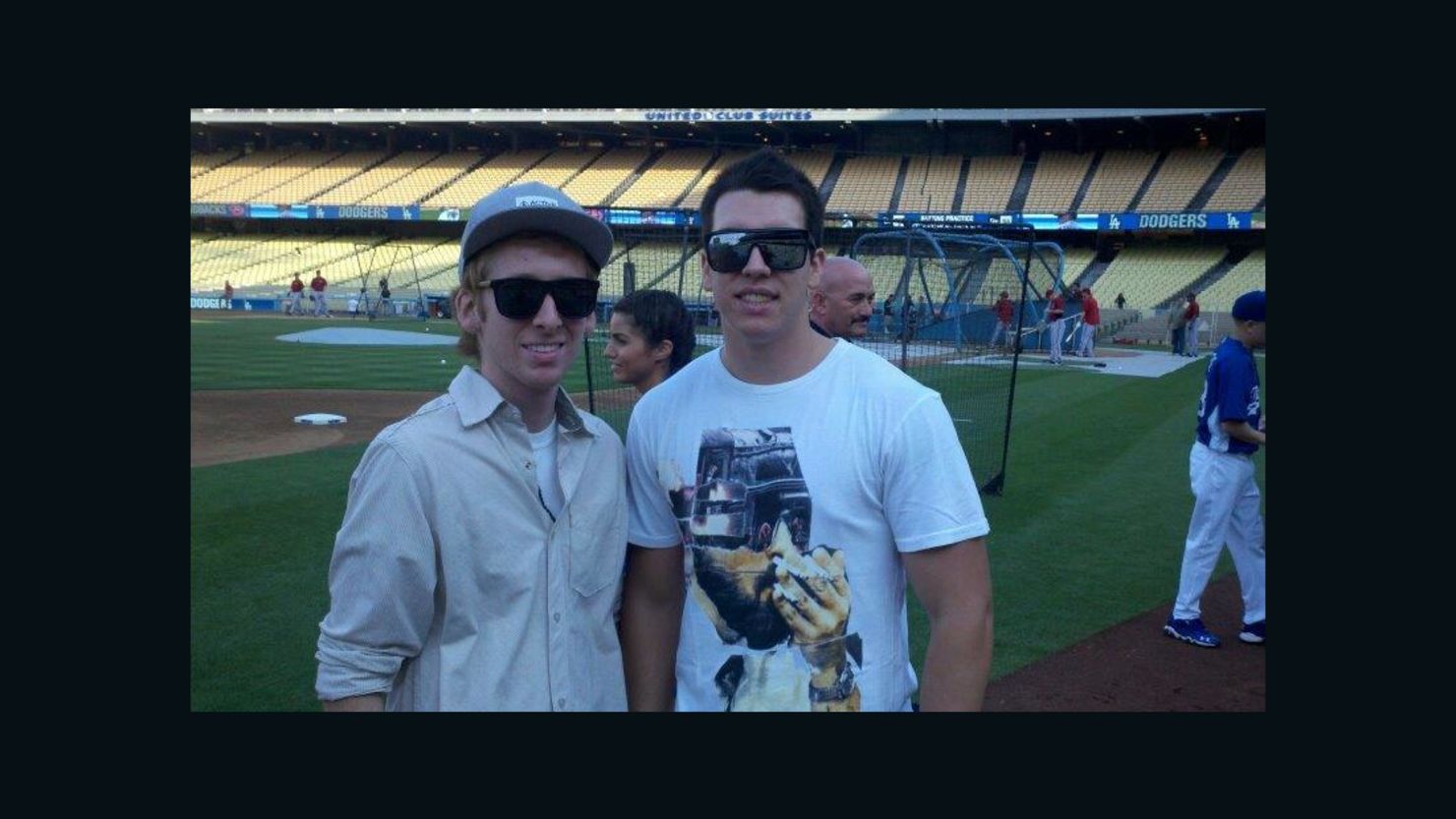

In my early 20s, I stopped caring about who knew I was undocumented. It’s not like something I chose. It’s not like it made me un-American. I told three of my closest friends about it and they could not believe what I was telling them. They couldn’t believe that someone like me, who looks so white, could be an undocumented immigrant.

Now I’m 25, and I have learned a lot. I come from a beautiful culture of people who are full of tradition and I am proud of it. To this day, I’m still asked what ethnicity I am. When I tell them I’m Mexican, they just look at me in confusion and ask if I speak Spanish. When I respond in Spanish, the look on their faces is just priceless.

After President Barack Obama signed an executive order in 2012 allowing children who had entered the country illegally to remain and work, I applied for relief from deportation. It took a couple of months, but in December 2012, I got the good news. I couldn’t help but think about all of the possibilities that could come, like getting a good job and a driver’s license.

But it was bittersweet. I still wish I had a way to travel outside of the United States. I know the first place I would visit: I’d go to Mexico.

Opinion: The undocumented are us

If you’ve immigrated to the United States, we want to hear your story. What was your path to citizenship or residency like? Share a personal essay about your experiences with CNN iReport.