Story highlights

The violence in Israel and Gaza hits close to home for those with relatives involved in conflict

Children in the U.S. talk to their cousins in Gaza over Facebook and Twitter

Palestinian-American comedian with connections to violence confronts conflict on stage

Every morning, Asya Abdul-Hadi wakes up in Denver and begins what has become an agonizing routine.

She looks at her phone and computer, a knot in her stomach, hoping to see that all her siblings and members of her large extended family in Gaza have left a message.

“It will usually be short. No one has time. They just tell me, ‘OK, we’re alive, we made it another day.’ “

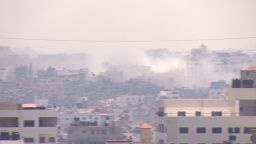

The conflict between the Palestinian militant group Hamas and Israel is raging far from the United States. For some, it’s a war on the news, another round of deadly dysfunction in the Middle East, a back-and-forth one-upmanship among politicians.

But for many in the States, it’s a deeply personal tragedy that fills them with anxiety about their family members in Gaza and Israel.

Israel-Gaza conflict felt around the world

Abdul-Hadi grew up in a refugee camp in Gaza, but her education at United Nations schools allowed her the opportunity to leave the area and go to college. In her 20s, she began to see a world that, at that time, was more free. She explored Jordan and Egypt, excelling in English and other subjects. The 50-year-old returned to Gaza for years to work as a journalist, then married an American and moved to the U.S. in 1997.

Now her children, ages 9, 12, 15 and 16, communicate on Facebook and Twitter from Colorado with their young cousins in Gaza. The kids write: “Are you eating? Are you worried more today?”

One of Abdul-Hadi’s sisters-in-law in Gaza told her that a 5-year-old niece has taken to clutching the Quran, holding it out like a shield and praying loudly.

“I know my nieces and nephews are very afraid right now,” Abdul-Hadi said. “They aren’t sleeping. They aren’t eating. There is nothing to eat. I think about where I am, my comfort, and then I think about them.”

A few times since late June when the Muslim holy month of Ramadan began, Abdul-Hadi’s children have whined about feeling tired or hungry.

“I tell them, ‘C’mon, remember that at the end of the day, at least we know we are going to eat,’ ” she said.

It’s a timeless and reliable retort from any mom: Zip it and think about other kids who have less than you.

But in this situation, it’s heavier. And Abdul-Hadi knows she doesn’t have an explanation for the larger “whys” that her children ask.

She doesn’t know what to say about the deaths of innocent people in a Gaza hospital that several artillery shells struck this week. Those four little boys who died while playing on a beach in Gaza City? There’s nothing that makes sense about that.

Opinion: Four dead boys: this is what war looks like

Then there’s the ultimate question: How did it all start? Will she say that the current bloodshed has roots in the kidnapping of three Israeli teenagers, a crime that was followed by the abduction and killing of a Palestinian teenager? What about the video showing Israeli authorities beating another teenager, an American visiting his family in the region?

“For me, I wish it to stop, for the violence to stop so that my family is safe,” she said. “But I also understand why people in Gaza fight. They want their dignity. I cannot blame them.”

Two mothers, two sides

Another mother in California also wants the fighting to end, and she also feels like Israel is doing the right thing.

“I am sorry for children … on whichever side,” Evie Steinberg said as she wept before a crowd at a Sunday vigil in West Hills, California.

Her 24-year-old son, Max Steinberg, was killed over the weekend during Israeli military activities in Gaza.

“I never thought I’d have to bury a child,” she said. And while she supports Israel’s actions in the conflict, she also feels for innocent Palestinians who have been hurt.

“I’m not here to be hateful to the Palestinians … ” she said.

In a Washington Post interview this week, Evie Steinberg said that her son changed after a free 10-day birthright trip to Israel in 2012, sponsored by a private foundation. He didn’t want to go at first, but before the year was over, he had become a sharpshooter with the Israeli military, she said. Steinberg was reportedly part of the forces’ Lone Soldiers Program, which supports service members whose families live outside Israel. More than 2,500 people from 60 countries are in the program. About 740 are from the United States.

The soldier’s Facebook profile picture was changed on June 30. He apparently replaced a picture of himself smiling and snowboarding to one in which he’s wearing a serious face and combat gear, and cradling his weapon.

This week, people from the U.S., Israel and elsewhere have left many comments such as “Thank you for protecting our homeland.” Others called him a “hero.”

“He did what he wanted to do,” Evie Steinberg said at the vigil. “He has his friends, his fellow soldiers, his brothers. I know that he would probably want to be laid to rest with them.”

The mourners sang “Oseh Shalom,” a prayer for peace.

Young men far from home

On Monday night in the Israeli city of Haifa, a funeral for another American who joined the Israeli military attracted thousands. Many didn’t seem to personally know Sean Carmeli, a 21-year-old from Texas’ South Padre Island.

Friends posted messages on social media worrying that the American didn’t know enough people in Israel and few would attend. Word spread quickly. Carmeli had a full military funeral, said Maya Kadosh, deputy consul general of Israel to the Southwest, and as many as 20,000 people showed up.

Carmeli’s journey to Israel’s military began with his parents’ desire that he and his sisters foster a deeper appreciation for their Jewish faith and heritage, said Rabbi Asher Hecht, co-director of Chabad of the Rio Grande Valley.

Carmeli’s parents moved to Israel, where Sean finished high school, and when the couple returned to Texas, the young man stayed behind, said Hecht.

Eitan Moed, an 18-year-old who moved from the U.S. to Israel, told Israel’s Haaretz newspaper that the two played American football together while they attended high school.

“He was a kid who always smiled and he just came off as a happy sort of person,” Moed told the newspaper.

While the Carmelis and Steinbergs mourn, some other American Jews try their best to check in with relatives who are in Israel.

Jeff Knishkowy, a lawyer in Chevy Chase, Maryland, has several family members to worry about.

His brother and sister-in-law live in Israel, as do his three nieces and a nephew who are members of the Israel Defense Forces.

“I talk to my brother more regularly than I normally do,” he said.

He trusts that the Israeli government knows what it’s doing. What else can he do from so far away?

Knishkowy constantly checks news apps on his phone for English-language outlets such as Haaretz and the The Jerusalem Post.

He tries to keep his sons, ages 10 and 12, away from most of the graphic content of stories.

“We all want the violence to end,” he said. “We all do.”

A Palestinian-American trying to find the funny

Comedian Aron Kader’s father is Palestinian. His mother is Mormon. The Los Angeles-based performer likes to mention that during his shows. It sounds like the beginning of a joke.

As much as he cringes at the lameness of the “Can’t we all just get along?” mantra, his jokes stand on that philosophy, he said. And he believes it, even after the brutality wrought on members of his extended family this summer.

One of his distant cousins is Mohammed Abu Khedair.

The 16-year-old was hit on the head with a blunt object and burned alive, according to Palestinian General Prosecutor Mohammed al-Auwewy, citing a medical autopsy. Several Israeli Jewish suspects have been arrested in connection with the slaying, Israeli police said.

Kader had never met the teenager, but his death hit the comedian hard.

“I didn’t know I’d be as affected as I was. I started to read the news about how he was a joker. I mean, the children have absolutely nothing to do with it. It’s about terrible leaders.”

At a recent family reunion in the U.S., everyone debated whether they wanted to turn on the news.

“Should we or not? Will it just make us more upset?” he said. “As a person, as a human, it’s just difficult every day to pull away from it, but it’s also hard not to confront.”

Another of the comedian’s cousins, Tariq Abu Khdeir, made global headlines the first week in July when he was seen on videotape being pummeled by Israeli police in Jerusalem. The 15-year-old, who was born in the U.S. and lives in Tampa, Florida, was in the West Bank visiting relatives.

Speaking to CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, Tariq said that he now has an idea of what his relatives face.

“What they go through, like the people that are dying in Gaza – it’s really sad … having to go through all that pain,” he said.

What happened to him is “just a taste of what they go through,” he said. “You have people dying all over there. It’s sad.”

Kader said he doesn’t talk about Mohammed’s death on stage. It’s just too intense.

“I’m allowed to be an optimist as a comedian, I want to be able to express myself,” he said. “I don’t think my job is to go out there and tell a Palestinian story.

“But to deal with it (on stage), I also have to be cynical, I have to use gallows humor,” he said.

Sometimes it can feel maddening to the comedian that the violence today doesn’t feel much different from violence that’s happened between Israel and Gaza for years.

“I’ve recycled old jokes even. It seems like there has to be blood every few years, like that is the way it is and it won’t change,” he said. “It’s all dehumanizing. We want everyone on both sides to see the other as less than human. But I don’t know who, on either side, would say they don’t want it to end.”

Americans who fight for Israel

CNN’s Holly Yan, Polo Sandoval, Janet DiGiacomo, Martin Savidge and Amanda Watts contributed to this report.