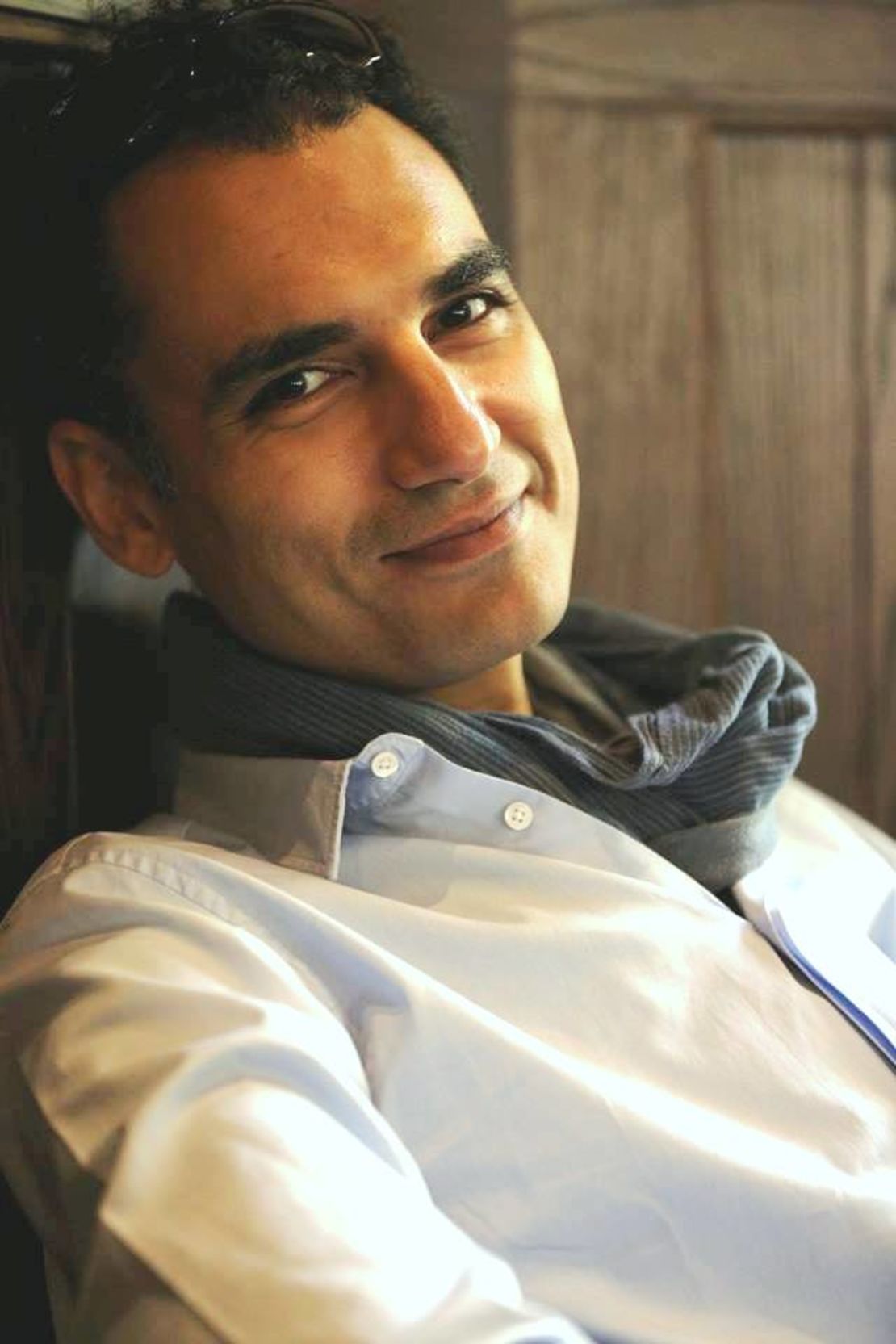

Editor’s Note: Motez Bishara is a London-based author and freelance journalist. His book, “Beating the NBA: Tales From a Frugal Fan,” serves as a critical analysis of the ticketing industry and a guide to purchasing discounted tickets to live events.

Story highlights

Luis Suarez returns to club football this weekend after four-month ban for biting

Experts say some players react better than others after receiving long suspensions

Suarez had already been banned twice for biting before latest indiscretion at World Cup

Ex-goalkeeper Mark Bosnich says players need emotional, professional support

Although he’s vowed to keep his famous chops to himself, the world will soon find out if Luis Suarez can keep bagging goals without literally leaving his mark on defenders.

This weekend, the 27-year-old forward will complete his four-month ban for a third on-pitch biting offense, and could make his Barcelona debut in the battle known as “El Clasico” against Real Madrid on Saturday.

“Don’t worry, I won’t do that again,” the gifted Uruguayan promised, soon after arriving at his new club.

But will he?

How players are affected when they face lengthy suspensions can vary between recovery and meltdown depending on their support network, according to football insiders.

And surprisingly often, that support network is lacking.

“If someone has done this a third time, I’m not sure he can change so easily without addressing the issue,” says Roger Barnes, founder of London-based agency Sports Management International.

“You would expect FIFA to say as part of the ban you have to do ‘x’ amount of counseling. Adding the counseling bit did not take place.”

It almost never does.

World football lacks both a formal system of preventative measures to avoid infractions and a consistent aftercare program for suspended players.

This, despite the proliferation of cameras (on and off the pitch) and the hazards of social media that have players sitting out for a wider range of offenses than ever before.

Those who are exiled from their clubs, as the initial terms of Suarez’s ban stated, are especially fragile.

Suarez’s punishment, handed out during the World Cup, initially banned him from all football activities including attending matches as a fan.

Instead of demanding treatment, FIFA ordered the player away from his workplace after a series of ineffective bans.

Suarez had already missed 10 matches in 2013 and eight games in 2010 for biting opponents, along with another eight for a highly scrutinized onfield racial incident in 2011. Liverpool, his club at the time, supported Suarez’s denial and counseling was not part of his suspension.

But isolating him since July could easily have made matters worse says Stephen Smith, chief psychologist for Sports Psychology Ltd.

“At the moment, we just ban these players and leave them to their own devices. From a psychological perspective it’s highly dangerous and puts them at risk.”

Upon appeal, Suarez’s training privileges with Barcelona were reinstated on August 14. That could make all the difference to his wellbeing according to Smith, who consults for English Premier League teams and players.

“Some of them don’t know how to pay their phone bill or anything simple like that, because everything is done for them,” Smith says.

“When the support mechanism switches off they just don’t know what to do.”

Smith asks whether governing bodies like FIFA and football federations could do more in terms of rehabilitation and questions what responsibility they have to players as regards their duty of care.

Barnes, who represents top-tier footballers in England and the United States, says that the reasons may be financial.

“There would be a whole pile of players who say if you’ve paid for Suarez’s (counseling) can you pay for mine? FIFA has no monetary gain.”

The decision to provide therapy, therefore, falls on the player’s club – which will often weigh in his value to the team.

Liverpool wisely hired Dr Steve Peters, famous for harnessing the rogue instincts of athletes, halfway into Suarez’s tenure.

Five months later, however, the goal-scorer sunk his teeth into Chelsea’s Branislav Ivanovic. He remained a work in progress for another 14 months until his World Cup relapse.

Suarez remains coy on whether Barcelona has taken Liverpool’s lead, saying only that he has “dealt with the appropriate professionals.”

But the Catalan club – which paid a reported $130 million for the striker in July – has strong financial incentives to maintain his care.

“You don’t want to see your assets depreciate in any shape or form,” says Barnes.

Not every player is as fortunate, however.

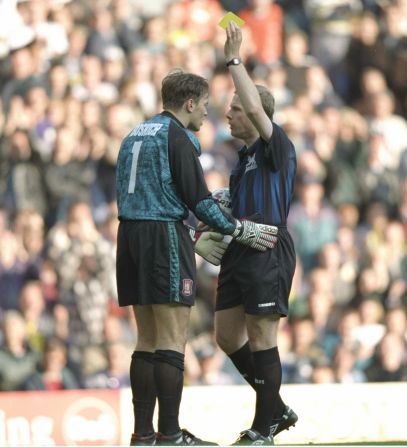

Former Chelsea goalkeeper Mark Bosnich was banned by England’s Football Association in 2002 for a still-record nine months after testing positive for cocaine.

“When I was away (from football), that’s when I went completely off the rails,” he told CNN, adding that neither Chelsea nor the FA provided him with recovery options.

Instead, the Australian was immediately dropped by his club for breaking the terms of his contract.

“Chelsea probably figured they didn’t see a future with Bosnich,” says Barnes. “For them it was an ideal opportunity to site gross misconduct and get his deal off their books. It’s a matter of supply and demand.”

Suddenly the then 27-year-old, who had previously starred at Manchester United and Aston Villa, was jobless for at least a season.

“I had a lot of free time and a lot of money. Hanging around the people I was hanging around, it was conducive to what happened.”

Lacking the structure of professional football, the Socceroos international quickly fell into a raging drug habit. It was his agent who suggested he attend rehab, though he was released soon after arriving.

That’s when things took a turn for the worse. “What I thought was obviously everyone thinks I’m guilty so who cares,” he says.

To avoid these pitfalls, Smith suggests shortening bans for players who demonstrate recovery, while keeping them on watch.

“Just as a prisoner can go on parole for good behavior, you give them an incentive to get back into the game quicker and to be better players.”

Bosnich, currently an analyst for Fox Sports in Australia, stresses that the best therapy possible is to keep on playing.

To him, losing his salary (nearly $3 million) hurt far less than missing the action. “You can talk to all the people in the world, but the same things can happen again. Training and playing football is your therapy. It’s your whole life.”

As for Suarez, Bosnich says letting him practice and play friendlies for Barcelona has been “important and completely fair.”

He notes that their cases are entirely different; Bosnich’s parents remained in Australia while he sampled London’s nightlife, whereas Suarez’s wife and children are with him in Spain.

“That’s a really important thing as well, the environment that you’re in, the people around you,” he says.

“What I found out later is the worst thing is that you have nothing to do.”

Smith agrees. “If you look at the issues that have plagued a lot of footballers – drinking, gambling etc. – one of the major reasons for that is when they’re not training there is a huge amount of boredom,” says the psychologist.

“And when they are bored, and they are outside of the safety network, that’s when the devil makes play for idle hands.”

The idle hands of professional athletes these days are shifting away from the casino tables and onto social media, where an impulsive tweet can cause uproar in an instant.

Although the Premier League issued guidelines on social media back in 2012, it wasn’t until this season that its first player was suspended for such an offense.

In June, the FA made history by banning Yannick Sagbo from Hull City’s first two matches of 2014-15 for a racially insensitive tweet, which he posted in support of Nicolas Anelka after the former France star’s “quenelle” gesture in an EPL game last December.

The FA cited the previous terms ordered by an independent panel as “so unduly lenient as to be unreasonable,” even though the Ivorian had agreed to attend an education course and pay a fine of £15,000 ($24,000).

Queens Park Rangers manager Harry Redknapp currently fields two players who have served some of the longest bans in Premier League history.

Rio Ferdinand lost eight months of football in 2004 for a missed drug test at Manchester United, while Joey Barton served a 12-match ban for violent conduct in 2012. He also spent two and a half months in prison in 2007 for an assault charge, checking himself into Alcoholics Anonymous soon after.

Both of the players also happen to be very active on Twitter, boasting nearly 10 million followers between them.

“I don’t follow Twitter or social media. I wouldn’t have a clue what they’re even on to be honest with you,” says Redknapp, when asked whether the club has a policy on the matter, given the prospect of potentially losing players over loose comments.

“Obviously you can’t afford to have people suspended and missing games. It can be (worrying), especially if I was watching them every day, but I don’t.”

Barnes, who advises his clients on social media etiquette, calls it “a minefield.”

“Clubs will catch up eventually, but it may well be forced on them when somebody says something out of turn.”

Whether Barcelona will have its hand forced all depends on whether Suarez’s convictions have any bite to them.