Trekking through the forest with hardened front line soldiers and living under the threat of American bombers: it’s not the normal experience for art school students, but it was one faced by hundreds in Vietnam during the country’s conflicts that raged between 1954 and 1975.

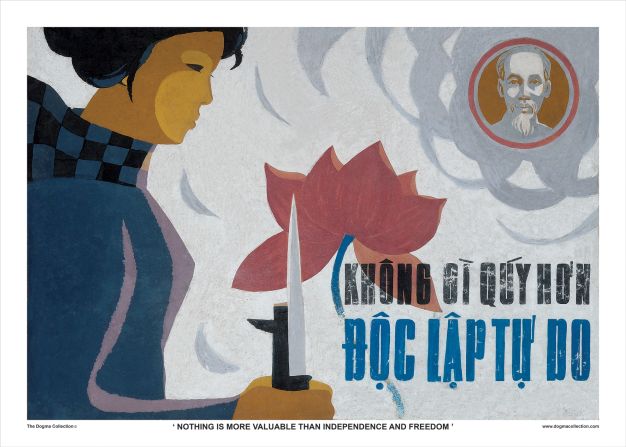

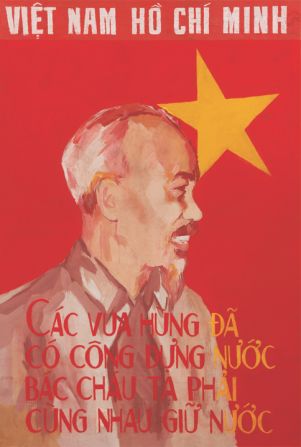

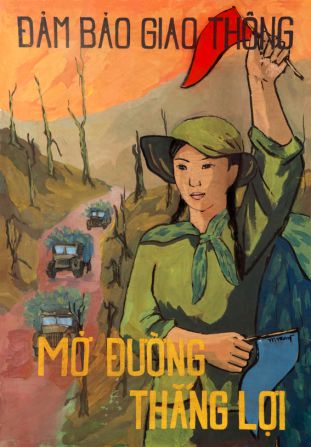

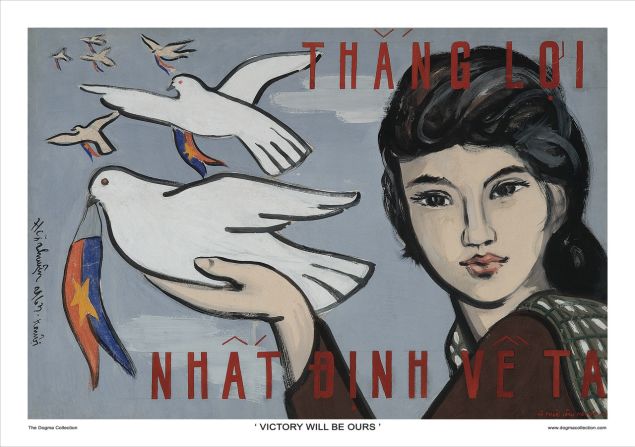

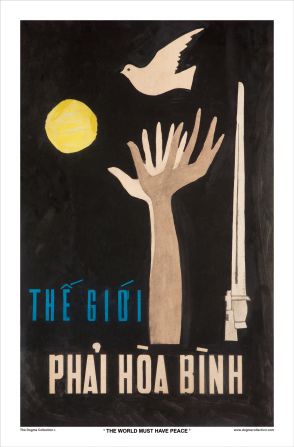

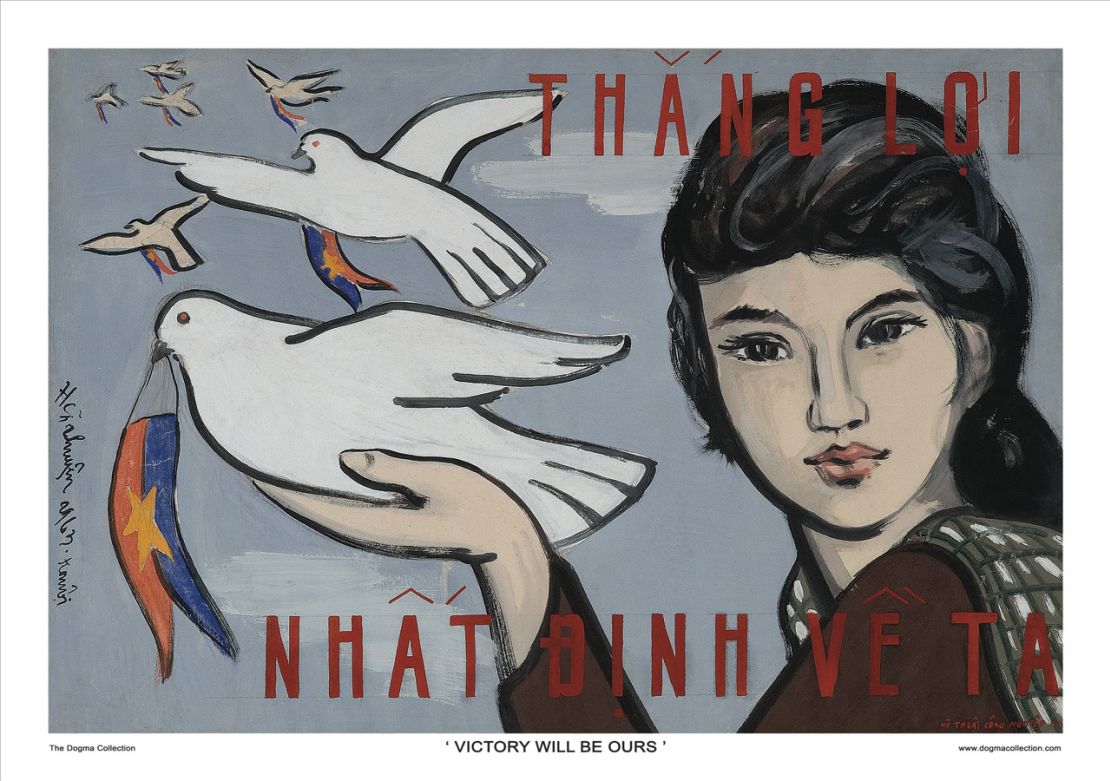

From post-colonial struggles to the battles to reunify a Vietnam partitioned after the 1954 Geneva Accords, North Vietnamese artists were key in taking the messages of Ho Chi Minh to the front line of battle and to a population across both sides of the divide. Visually arresting, cheap and effective, Vietnamese propaganda posters weren’t meant to last, but their messages were.

“The posters are a historical document but also illustrative of the use of art and development of artists in the country,” says Richard Di San Marzano, curator of the Dogma Collection of Vietnamese propaganda art and an upcoming exhibition of original posters in Ho Chi Minh City.

Di San Marzano says that there are around 1,000 original examples in the collection that was started by Dominic Scriven, a British investment banker who moved to Vietnam in the 1990s.

‘Artists are soldiers on the cultural front’

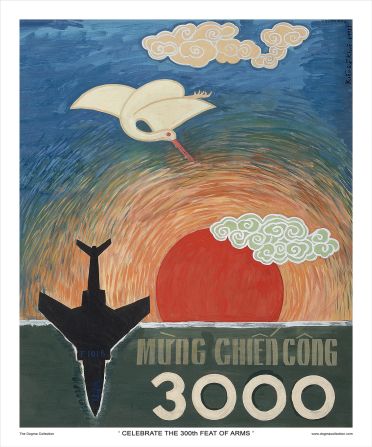

Unlike much Cold War-era Communist propaganda art, Vietnam’s was produced during active conflict, giving it a character, urgency and style all its own, believes Di San Marzano.

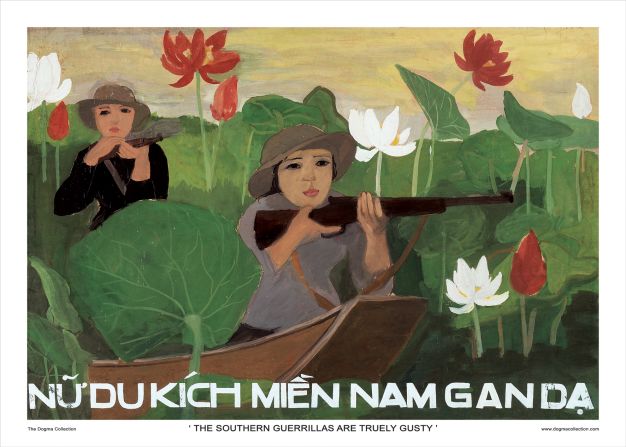

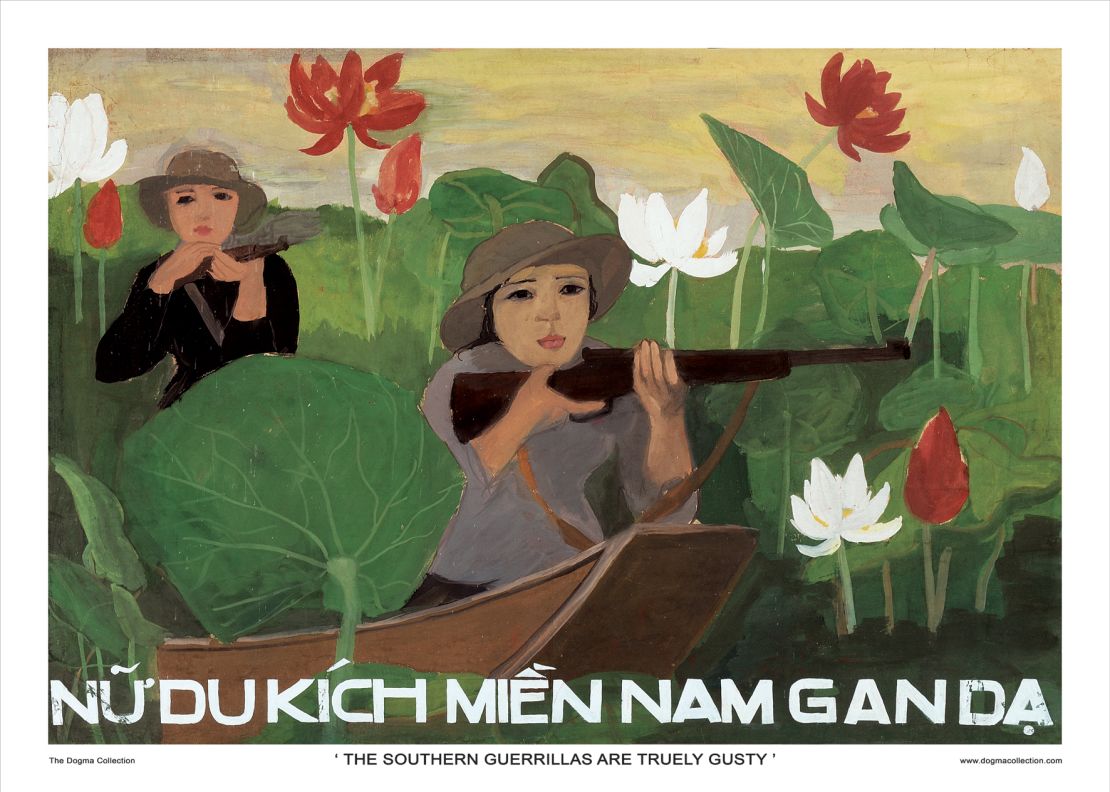

Expelling “foreign invaders” and celebrating military action, such the shooting down of American planes, were common themes. Also regularly featured: national symbols such as the lotus flower as well as communist iconography such as the face of Ho Chi Minh (“Uncle Ho”).

Women were portrayed in the posters in numerous roles, but particularly, and uniquely, believes Di San Marzano, as front line fighters. Yet a key difference to Soviet and Chinese propaganda art that Di San Marzano discovered was that most posters were signed by the artists.

“I was amazed to see signatures on around 80 percent of the posters,” said Di San Marzano.

He was then able to trace the whereabouts of some of the artists and embark on the project to “preserve and catalog as many posters as possible before they were lost forever.

In interviews, Di San Marzano was able to hear firsthand the hair-raising tales of those who embedded with guerrillas, many of whom were sent to villages in “enemy territory” to paint and display communist slogans. Imprisonment or worse was the punishment if they were caught.

‘Art is not art unless it is propaganda’

An artist himself, Di San Marzano has spent years building up a greater picture of the importance of propaganda art in Vietnam and of the people who painted them, since cataloguing the collection in 2007.

Under French colonial rule, art schools across Vietnam were established that taught students in a classical European tradition. But under the governance of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, commonly known as North Vietnam since 1945, an Artist’s Association was set up, mixing students from the School of Fine Art in Hanoi and artists without much formal training, often from rural backgrounds.

At that point Soviet socialist realism was the dominant style with the Association following the Leninist dogma that “art is not art unless it is propaganda.”

While some posters show more skill than others – some artists were able to continue their training in the Soviet Union or Eastern Bloc – Di San Marzano was surprised to see hints of art school individualism not quite submerged by centrally planned messages.

Art produced on the back of scrap paper

Many posters in the collection have classical life drawings on the backside, which Di San Marzano believes was more about making best use of resources rather than self-expression.

Produced quickly and often in the field – paints and paper were often scarce, especially after the escalation of the conflict in 1965 – many posters from that time are produced on the back of any spare material, including maps and Soviet bloc posters.

Regardless of their training or background, a common theme united the artists Di San Marzano was able to speak to: each was proud of the part they played to help their country.

“I wasn’t conscious that this was the making of propaganda art,” said Pham Thanh Tam, one of the artists he interviewed. “I simply thought of it as a means to help the public understand.”

“A Revolutionary Spirit: Vietnamese Propaganda Art from The Dogma Collection” exhibition at the Fine Arts Museum, Ho Chi Minh City, April 8-22, 2015. Ho Chi Minh Fine Arts Museum, 97 Pho Duc Chính, Nguyen Thai Bình, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam