Editor’s Note: This is an edited excerpt from a new book called “Hair” published by Assouline.

Story highlights

Celebrity stylist John Barrett's clients include Hillary Clinton and Beyoncé

His first book, "Hair," brings together photos history's most iconic hairstyles

There’s beauty in the luster of a woman’s hair – its heft and weight, its sheen and shimmer, the way it flicks behind her with the sway of her walk, or rises imperiously swept back from her face.

But there is also artifice. A part of her, and yet not her in the way hands and lips undeniably are, her mane lies in that interstitial space between adornment and essence, between authenticity and artifice. That’s what drew me to hair as a boy in Ireland: the chimerical quality, the ability it had not just to define, but to create a person.

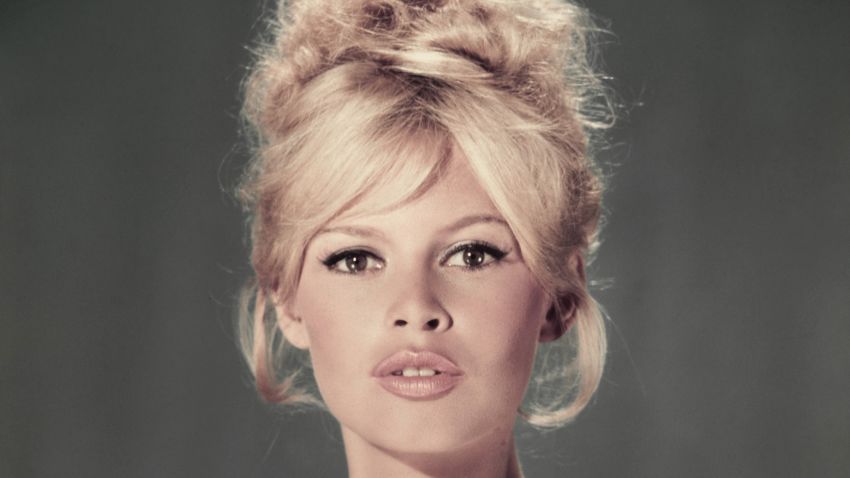

I saw in the personal style of Brigitte Bardot and Catherine Deneuve the ability of hair to augment – maybe even define – star power. They made claims about themselves through their hair. And I realized, so could I.

Finding perfection

As a child, it seemed to me that there were uniforms for special occasions. And the most special occasion was Mass. All of the women in their best outfits, similarly and immaculately coiffed. All the same except one lady, with her bold, bleached hair, her unending eyelashes.

Each week, I’d think to myself, “How could someone be so beautiful?” She stood out, demanded we pay attention to her. And we did. Or at least I did! I was totally captured.

She wasn’t a star—she worked at the bakery—but she commanded our attention. I was six or seven.

Read: Naomi Campbell celebrates 30 years of supermodel stardom

My curiosity was piqued, too, through film; the ladies of the Golden Age – Mae West, Greta Garbo, Barbara Stanwyck, Marilyn Monroe – each with hair more perfect than the last. (Of course I didn’t know this at the time, but they all wore wigs!)

The perfection I found absolutely magnetizing.

I moved to London in the early seventies. By this time, hair was strict. Structured. I remember encountering a woman named Bambi – one of these characters that figured heavily as an early inspiration to me, although I’m not sure she could pick me out of a lineup. She was a part of the Piccadilly Circus crew and had all of these extravagant hairpieces. It was nothing short of magic, and I wanted to have a hand in making magic. Always have done, always will.

When I started doing hair, my first instinct was, “Good God, why must they make this so complicated!”

To me, hair is quite simple. It should not distract, it should enhance. No fuss. Within seconds of seeing someone’s face, I see what is unique and special about them, and it is my duty to help draw attention to that. I’m always looking for the beauty that’s already there—and it’s always there.

A coif for revolution

Thousands of women have come to me to sit before a mirror and ask me to help enhance their beauty—indeed, I see what I do as no less than that. Are their expectations fair? To snip and shear, tousle and tease something they see inside themselves into the wider world? I can only do so much, they have to do the rest, I often say in that conspiratorial huddle of the hairdresser’s chair, but I can help.

I’m just one way station in the history of hair doing just that. The bobs of the Roaring Twenties allowed women the unthinkable—an edge of masculinity.

They bound their breasts and cropped their hair and danced with men and broke free of Victorian confines. Coco Chanel and Louise Brooks lead the scandal of female rebellion, with bouclé and tweed underscored by the freedom of cropped hair.

Read: 15 breathtaking hair and makeup looks from past fashion weeks

When in the sixties the hippies let their hair down, streaming tresses over peasant dresses, the flutter of tangled hair that slipped to the waistband of bell-bottom jeans, it was no less of a cultural event.

If she curled her hair, was she appropriating a bourgeois form of cultural viability, aligning herself with, say, a pro-war sensibility? If she straightened, or wore an Afro, was she suppressing and rejecting such an impulse? Was it possible to read hair for these sorts of cultural cues?

Of course it was. And is.

The next generation

Today it is the flexibility of hair, that there is no norm, which defines us. Now, ladies like Jennifer Lawrence and Rihanna move seamlessly back and forth between short and long, blond and brunette, as did Linda Evangelista and Madonna before them. Uniformity is the enemy.

Even someone like Hillary Clinton, who cares less about her hair than most people, and for whom nothing at all should detract or distract, allows me to remain flexible in what works. I’ve gained her trust, and given her one less thing to think about.

I’m not, nor have I ever been, interested in “the next big” anything—particularly as it relates to hair. I’m interested in making women feel beautiful – and reminding her that she already is.

This is an edited excerpt from a new book called “Hair” published by Assouline.