Editor’s Note: Alan Lau is a collector based in Hong Kong. He co-chairs the Asia Pacific Acquisition Committee of UK’s Tate Modern and Para Site, Hong Kong’s oldest contemporary art space. He also serves on the board of M+, part of the ambitious West Kowloon Cultural District project in Hong Kong.

Story highlights

Southeast Asian contemporary art has always drawn attention on the world stage but it's now coming into its own

Its art institutions are growing in stature and the region is rapidly expanding its own impressive line-up of art fairs

Lau selects some of his favorite works from the region in the gallery above

Not to be outdone by North Asia, which hosts major events like Art Basel every year, Southeast Asia is rapidly growing its own art fair line-up.

The inaugurating edition of Art Stage Jakarta attracted 15,000 people last month and pulled in collectors and curators to visit not just the city but the adjacent art hub of Yogyakarta, a thriving center for alternative art spaces in the region.

Critics seem generally positive about the spotlight that such an event helps to put on artistic practices in the region.

But, to be clear, Southeast Asian contemporary art has always drawn ample attention on the world stage.

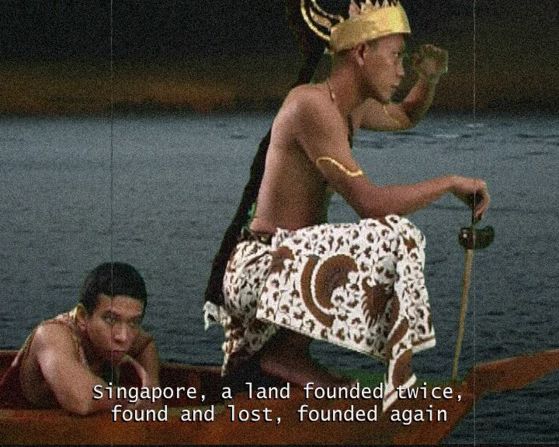

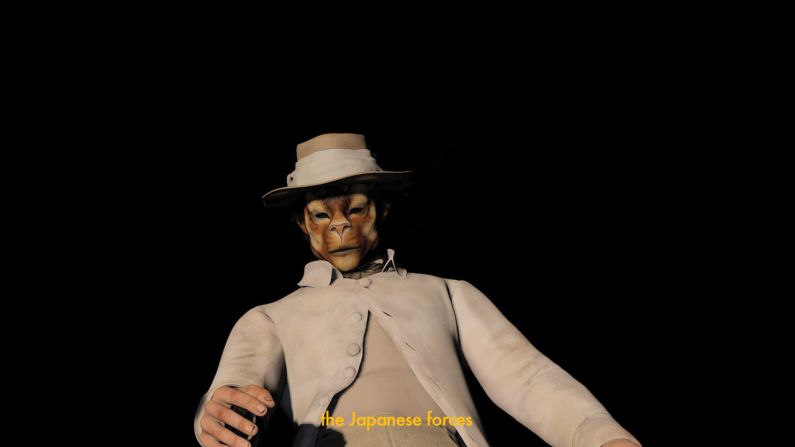

Ming Wong’s Singapore Pavilion in Venice Biennale 2009 won the Silver Lion Award with his video work referencing Singapore’s cinema culture in the 50s and 60s and Indonesia hosted its first national pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year with works from Heri Dono.

Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Asia Art 2015 prize went to Maria Taniguchi from the Philippines.

And Singaporean artists like Heman Chong, Ho Tzu Nyen, and Lim Tzay Chuen all recently showed in galleries and museums across Asia.Artists from the region are by no means ‘provincial’ or appeal only to Asian audiences.

Rirkrit Tiravanija from Thailand is a recognized global pioneer of a school of art called relational aesthetics, art that is not just a painting or an object but “a constructed social experience” where the audience becomes part of the work.

In his landmark work, ‘Untitled (Free)’, he turned a gallery into a kitchen and cooked Thai curry for visitors to MOMA. He is a professor at Columbia University, and has influenced rising star Korakrit Arunanondchai, also originally from Thailand and now based in New York.

Korakrit, just 30 years-old, already has a hat-trick of exhibitions at MOMA PS1, Palais de Tokyo, and Beijing’s UCCA with his seminal denim paintings and burnt mannequins that talk to pop culture, music and religion.

Defining “Southeast Asian”

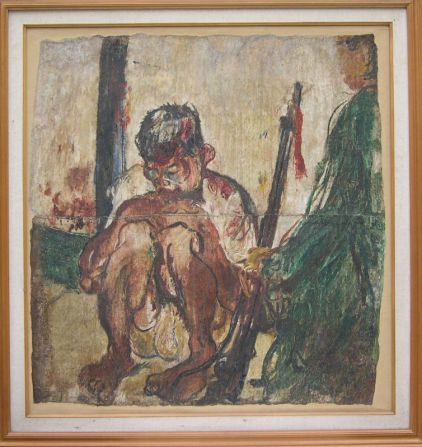

While auction houses might draw ‘hard’ regional lines to fence-in what is Southeast Asian art – which typically involves artists based in the region including big names like S. Sudjojono and Affandi – art lovers do not need such strict taxonomy.

There are many artists who were born in Southeast Asia but who now live and work outside the region and produce works that are richly informed by their own history and experience.

Take Danh Vo for example. Born in Vietnam in 1975, he fled the country when he was four years old on a family boat intercepted by a Danish container ship. His themes of displacement and identity resonate with a global audience.

One of his most recognizable works, called ‘We the People’, recreates the Statue of Liberty as 267 fragments and disperses them all across the world as standalone abstract sculptures.

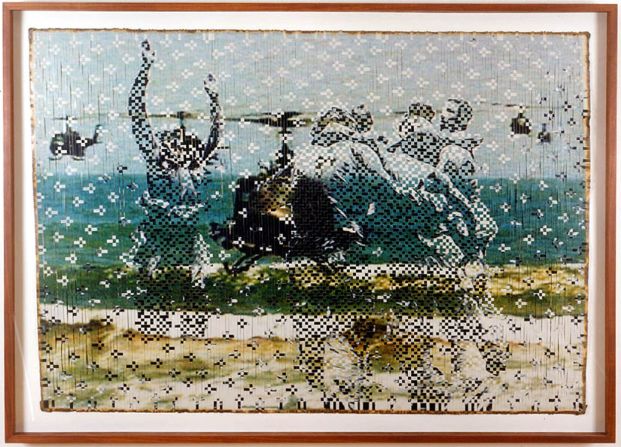

Dinh Q Le, who left Vietnam at age 10, produced works about the Vietnam War by observing it from a distance while he was studying in the US at the time.

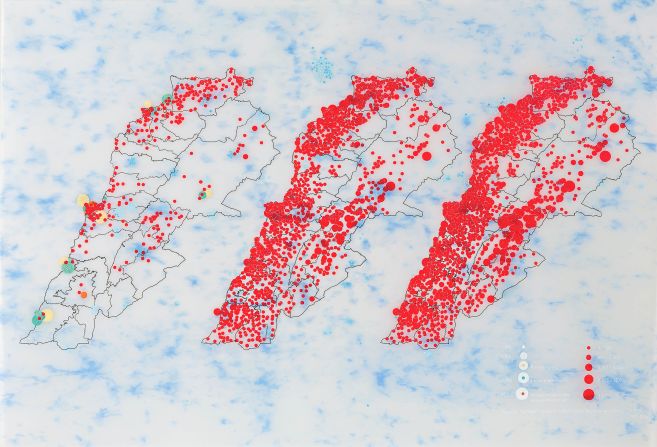

Last but not least, US-based Tiffany Chung’s work feature themes of war and conflict, and she regularly returns to Vietnam which inspires and informs her practices.

Connections, not countries

Of course, labeling an artist by his or her place of birth can be a dangerous shorthand, and is often resented by artists – for good reason.

Forward-thinking institutions are taking note, and doing less ‘country shows’, and more exhibitions that find connections in similar practices from vastly different locations.

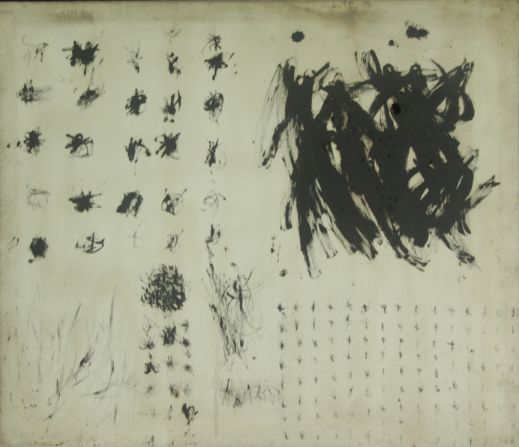

Para Site Art Space, Hong Kong’s oldest exhibition-making gallery, hosted a show about abstract modernism which put American Robert Motherwell, Brazilian Japanese Tomie Ohtake and Thai Chinese Tang Chang together and explored connections among their abstract works.

Centre Pompidou will be showing Tang Chang’s work next, putting his acclaimed art next to iconic Western artists such as Leger and Chagall.

The Tate Modern, long a proponent of telling a global story by including works from all over the world, is now giving a prime spot to another master, Apichatpong Weerasethakul from Thailand, in its new wing called the Switch House.

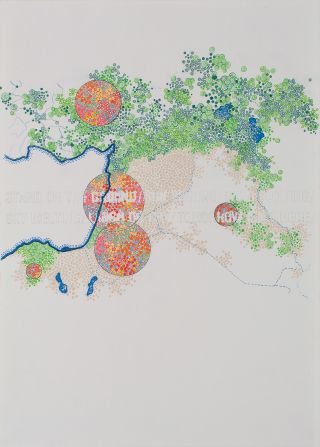

The ambitious multi-channel video work, called ‘Primitive’, is described by the Tate as a “sci-fi ghost story rooted in Thai folklore”. The work was one of the earliest Southeast Asian works acquired by Tate’s Asia Pacific Acquisition Committee to become part of the Tate Collection, a validation of Apichatpong’s status in the art world.

The ecosystem

While Western institutions are actively exhibiting works from Southeast Asia, Asian institutions are not leaving it to the West to take the narrative on what defines Southeast Asia art.

The newly-opened National Gallery Singapore, led by director Eugene Tan, is taking back the storytelling by giving works and artists from the region some much-needed spotlight. Its Southeast Asian collection is second to none, and there is no better place to see it than its new home, which used to be the magnificent old Supreme Court and City Hall of Singapore.

The Gallery’s recent programs include focal shows on Southeast Asia as well as ambitious collaborations, like ‘Reframing Modernism’ with Centre Pompidou, which placed works from the region against those by Picasso, Matisse and more.

Certainly the art “ecosystem” will not be complete without collectors and patrons, and Southeast Asia is very much present in this scene.

Uber-collectors like Indonesian Budi Tek are building art spaces to display their collections not just in Southeast Asia but in art hubs like China (via his Yuz Museum in Shanghai) to fuel the regional dialogue.

It will more likely be such exchanges across regions – by nomadic artists, borderless curators, global citizen-collectors – rather than a strict definition of ‘Southeast Asian art’ that will shape what we can expect from the region in the years to come.