Story highlights

"The Timbuktu School for Nomads" records a journey from Fez, Morocco to Timbuktu, Mali

Nicholas Jubber traveled with nomads and witnessed the effects of Islamic militancy

He points to nomads as providing lessons in countering extremism and climate change

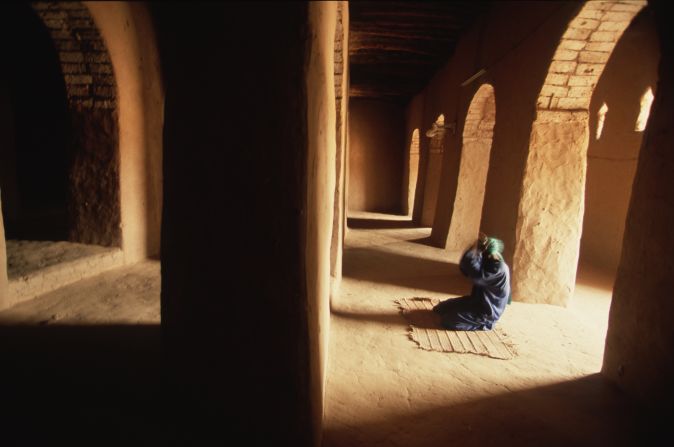

The Sahara’s shifting sands are as impermanent as the camps made by those who call it home. What remains a constant is the lifestyle that has kept nomads circling this unforgiving environment for millennia.

But for how much longer? The dual forces of jihadism and climate change threaten to upset a way of life that has endured both colonialism and dictatorship, but may not be able to match terror and Mother Nature. Yet one author suggests nomads may well be the people to teach the rest of the world how to tackle both.

The road to Timbuktu

Author and journalist Nicholas Jubber paints a remarkable picture of steely determination and true grit in new book “The Timbuktu School for Nomads: Across the Sahara in the Shadow of Jihad”.

Seeking to follow in the footsteps of 16th-century explorer Leo Africanus and travel between Fez, Morocco and Timbuktu, Mali, “it wasn’t so much ‘crossing the desert’ that spurred me,” Jubber writes, “it was the prospect of traveling in the desert… I just wanted to meet the people who lived there.”

What Jubber hadn’t counted on was the Arab Spring.

“When I started traveling in that part of Africa things started to go wrong, and the conflict in Mali … in 2011 to 2012 started breaking out… I got to experience a lot more of that than I’d originally anticipated,” he recalls with a wry smile, speaking to CNN.

Destabilization in Libya had spread south and with it Tuareg rebels, backed by Islamic militants, who claimed Timbuktu in 2012. Islamic militants, including members of al Qaeda-allied Ansar Dine, soon supplanted the Tuaregs, vandalizing monuments at the UNESCO World Heritage Site and imposed Sharia law.

The occupation would derail the writer’s journey and force him to return at a later date, once French-led forces had reclaimed the city in January 2013.

‘A very combustible combination’

When Jubber returned he describes “a place that was really being wracked terribly by political events.”

It was a city attempting to rebuild its culture, destroyed either at the hands of militants or removed out of necessity, such as ancient manuscripts from the city’s library, shipped down the Niger River to Bamako for safekeeping. A more immediate salve was the sound of music once more on the streets of Timbuktu, previously banned under the Islamist regime.

Jubber says although Tuaregs played a part in Timbuktu’s fate, the situation is complex – and perhaps contains a lesson.

“There’s a place called Agouni, just north of Timbuktu in the desert, and I met a lot of people from there who […] had their flocks taken, rustled, their medical supplies, their equipment stolen,” he recalls. “That was just before the jihadist armies started roaming through the Sahara.

“These armies start coming along and offering wages to the young men to join up with their army, and many of them went along. Many didn’t, and went to refugee camps and took other options, but some young guys did go and join the jihadist army because they were given a salary and a sense of self-worth.”

Chosen for the frontlines, many of these expendable hired guns died.

“It was a striking example to me of the way that extremist ideologies and economic deprivation join together – and it’s a very combustible combination.”

The writer sees a parallel between how nomads have been treated in recent years and the fate of the desert. For instance in Mali – where a tenth of the country is nomadic – Jubber writes that the government has given preference to agriculture over herding, “enshrining ‘the creed of private property.’”

“If [nomadic people] were given better investment, better help to have a more flourishing life out there, then few of them would be tempted into those kind of lifestyles and would be helping to protect it I think,” he argues.

“They can be guardians of these places and deserts where narco-trafficking or jihadism, banditry, so many of these things pass through. It’s the nomads really who can look after those areas.”

The first climate change war?

On his odyssey Jubber rides the iron ore train into deepest Mauritania, works in the tanneries of Fez and fishes on the Niger River. But he’s in awe of the desert tribes’ nomadic lifestyle: Fulani herdsmen, or the salt caravans dealing in the Sahara’s ‘white gold’.

“Surely,” he writes, “any lifestyle that has endured so long has something to teach us.”

“I think it’s really interesting that in apocalyptic fiction the people who can survive and flourish are the nomads,” he says, “who can forage and keep moving and adjust to whatever is being thrown at them.”

It would be premature to say nomads face an apocalypse today, but their struggles may soon be ours.

“So many of the issues being faced in nomadic communities – especially things like flooding, drought, water scarcity – are the issues that are going to be spread out on a much wider spectrum across the world according to a lot of projections,” he says.

Jubber describes the Sahel, the semiarid belt south of the Sahara, as “the setting of the first climate change war,” where conflicts are emerging over resources, particularly water and herding corridors. “When people are living on such narrow margins of survival, these things can become so explosive,” the author adds.

Investment and adaptation is crucial for the region, Jubber suggests, citing hydrocarbon potential and solar technology being rolled out in Morocco.

“I think there’s a lot of potential for future prosperity,” he speculates, “but it’s all about how it’s handled and managed.” Quashing government corruption, he says, is “the hinge that’s really going to define a good or bad future.”

Jubber hopes some of this investment filters down to the nomadic people who have tamed these wild landscapes for centuries – and hopefully will maintain them for centuries to come. It’s possible that these people, constantly on the move, may well be the key to the region’s stability.

![The author and traveler was determined, however. "When you're in the middle of a journey you can become quite numb to the danger," he told CNN. "[You] just want to keep going to reach your goal or your destination, and you forget that there really are slightly frightening things going on around you."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/160901171457-tuareg-1.jpg?q=w_2498,h_1783,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)