Story highlights

Most buildings for the dead are cold, depressing, utilitarian concrete boxes

But architects around the world are now rethinking how they design for the dead

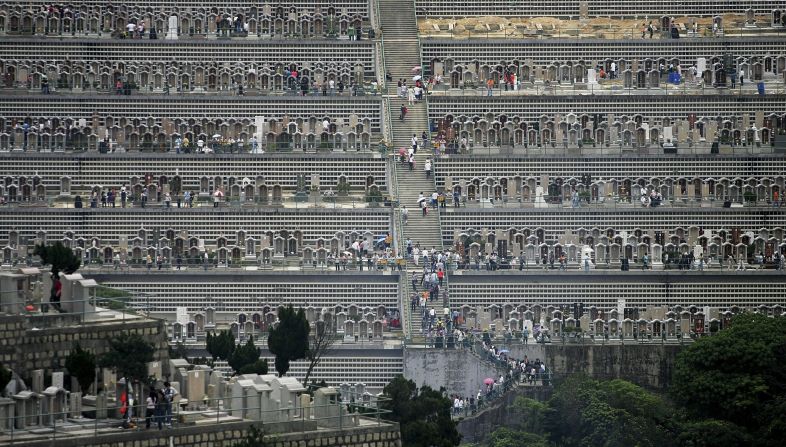

Crematoriums, morgues, funeral homes. These buildings, all of which are involved in rituals around death, often look as mournful as they sound. Designed to be discreet, they are usually cold and depressing utilitarian concrete boxes, tucked far away from the land of the living.

But architects around the world have begun to embrace death, designing symbolic structures that exude beauty, peace and a sense of intrigue.

“Crematoriums and morgues, including modern architecture, have always been challenging topics for architects,” says German designer Nikolaus Hirsch, who recent helped design a museum for the dead.

“But architecture can build a bridge between the living and the dead and, to some extent, blur the boundaries.”

From a Museum of Immortality in Mexico to a poetic morgue in Spain, designers are on a mission to inject more life into architecture for the dead.

Immortality by design

It was the connection between the living and the dead that inspired Hirsh’s thinking behind the “Museum of Immortality.”

Commissioned by Design Week Mexico and the Museo Tamayo for their October 2016 exhibition, the conceptual pavilion aims to stretch the field of design beyond tangible objects.

Inside Asia's surprisingly lively graves

Hirsch, who created the museum with his colleague Michel Müller from Studio MC, described it as an abstract attempt to offer immortality to humans, much like a museum’s approach to objects.

“It’s inspired by a two-fold conversation: the preservation of objects in a museum and the preservation of humans in mausoleums,” he says.

The concept pays homage to 19th century Russian philosopher Nikolai Fedorov and his notion of the ‘Common Task’ – a philosophy that explores resurrecting the dead through science and technology.

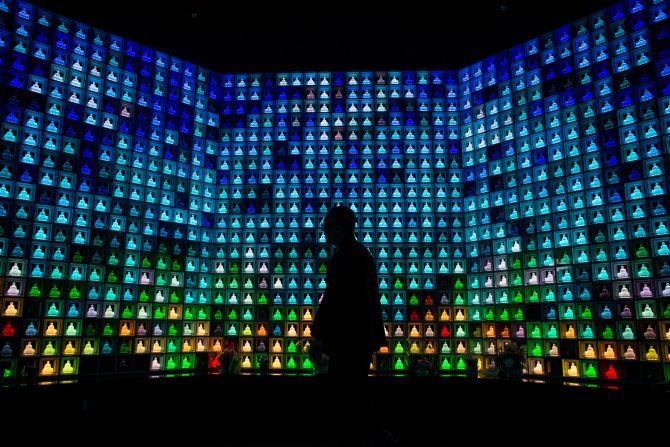

Indeed, Hirsch and Müller’s abstract interpretation brings to mind other-wordly pursuits. The 26 foot tall, hexagonal pavilion resembles a cross between a spaceship and a crypt, and was built using 15 layers of stacked acrylic boxes – some transparent and some opaque.

Each box is roughly the size of a human: about 5 feet, 11 inches long and just under 2 feet wide.

The futuristic appearance is also a nod to Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome, the world’s largest operational space launch facility, while the curving shape takes inspiration from the country’s geometric mausoleums.

Currently located in the Parque Bosque de Chapultepec outside the Museo Tamayo, in Mexico City, the free-standing structure will be on display until spring of 2017.

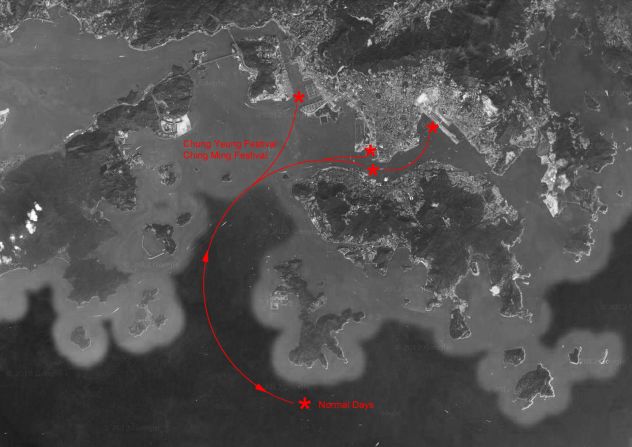

New ideas in New Delhi

Mexico isn’t the only place where architecture is rethinking death.

In New Delhi, 24-year-old Sanchit Arora, of Renesa Architecture Design Interiors Studio, has proposed a new approach to traditionally gloomy crematoriums.

Following in-depth research, that included his own grieving process, Arora found that the city’s public crematorium facilities are often poorly managed, run-down and located in dilapidated industrial areas.

Now in discussion with the New Delhi government, Arora is pushing for a more welcoming and nature-inspired crematorium zone in a South Delhi park that would alter the mourning experience completely.

“When my grandmother passed away, we saw the sad situation of crematoriums in New Delhi. They are left dirty and uncared for, and it’s just a sad state of affairs,” he says. “It just adds to your psychological distress during an already upsetting time.”

As cremation is a key part of a Hindu funeral, Arora set out to design a systematic yet approachable space that aims to soothe the living while they mourn the dead.

“What we saw through the process of my grandmother’s death is that, in the end, it’s not about the body. It’s about the people who are coming to mourn,” says Arora.

“When people die of old age in India, it is supposed to be a celebration. But there is a disconnect between the space and the celebration.”

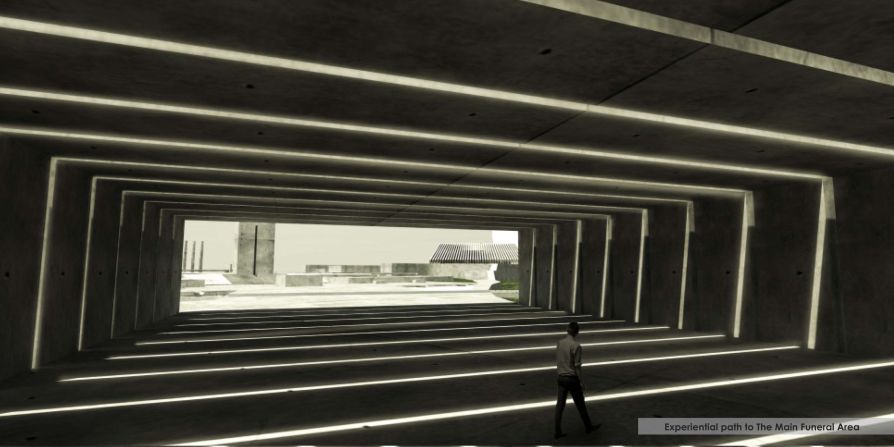

With exposed concrete, warm woods, and lush greenery all around, Arora’s design creates a minimalistic, zen vibe. There are quiet nooks and peaceful water features – all connected to a spacious park.

In Hindu culture, a funeral consists of several parts – it begins by viewing the deceased at home and is followed by bathing the body to purify sins. The body is then moved onto a wooden funeral pyre to be cremated.

Arora’s design not only introduces more environmentally-friendly electric cremation, it also streamlines each step of the process, with a logical path through the premises that offers organization and intimacy during the funeral process.

“Death is always going to be death,” says Arora. “But the translation of those spaces in terms of architecture and design changes from culture to culture.’

Peaceful passing in Spain

Across the other side of the world, on the outskirts of Zaragoza in Spain’s northeastern Aragon region, Tanatorium looks more like a spa than a morgue.

Designed by Juan Carlos Salas, the award-winning building has a sculptural appearance and every detail carries meaning.

“We tried to find the soul of the space,” explains Salas. “The plan of the building symbolizes a cavern. Visitors contemplate the deceased and explore their inner lives at the same time.”

Using a stereotomic architecture technique of cutting stones to form a perforated envelope, Salas created a cavernous atmosphere that’s meant to offer a sense of protection.

The 2,110-square-foot structure includes a diagonal roof, facing the sun as if to salute the heavens. It’s also a functional way to inject light into the rooms below.

Salas even visualized how light moved throughout the building – the roof’s slanted shape creates a shadow that shifts during the day, symbolizing the passing of time.

A peaceful and remote atmosphere evokes intimate feelings that Salas hopes will help mourners during a difficult time in their lives.

“Architecture won’t help deceased people, but it helps to keep their memories alive among the living,” he says. “The quality and symbolism of buildings like crematoriums and morgues are getting better every day.”