Editor’s Note: John W. Dean (@johnwdean) is a CNN contributor and former White House counsel to Richard Nixon. The views expressed in this commentary are solely his.

Story highlights

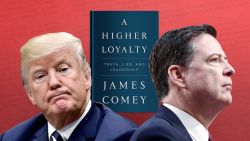

John W. Dean: James Comey is not testifying only because the president is not invoking executive privilege

Administration pretending otherwise is not only disingenuous, but also borders on small-bore fraud, Dean says

The White House has made an absurd announcement – that it will not invoke executive privilege to prevent James Comey’s testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee, scheduled Thursday.

Deputy press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders first claimed, “The President’s power to assert executive privilege is well-established.” So is the President’s power to issue pardons, but those are for another day. Huckabee Sanders proceeded from her non-sequitur, adding, “However, in order to facilitate a swift and thorough examination of the facts sought by the Senate Intelligence Committee, President Trump will not assert executive privilege regarding James Comey’s scheduled testimony.”

As a leading student and expert on the subject of executive privilege, Mark J. Rozell, has written, it is an accepted doctrine when appropriately applied in two circumstances: (1) certain national security needs and (2) protecting the privacy of White House deliberations when doing so serves the public interest.

Clearly, Donald Trump’s conversations with James Comey do not fall into either area. Trump was wise not to try to concoct a phony justification for using the doctrine, which at best would have been a delaying tactic and only increased the already-fiendish interest in the specifics of Comey’s testimony.

Pretending James Comey is testifying only because the President is not invoking executive privilege is not only disingenuous, it borders on small-bore fraud. To claim you have a power you do not, in fact, possess is dishonest. When executive privilege does exist, it is as the Supreme Court noted in US v. Nixon, always a “qualified privilege,” meaning there must be balance between presidential privacy and the public’s right to know – in contrast with other, absolute, presidential privileges, like the “state secrets privilege” (which the Bush/Cheney administration consistently abused, but was unavailable here for Trump).

This approach to former FBI Director Comey’s testimony is a drill symptomatic of the Trump White House. They either do not know what they are doing or when they do they believe no one else does, so they play games. In the annals of executive privilege, it has never been used to block the testimony of a former federal employee. To do so, the White House would have to go to federal court to try to persuade a judge to block Comey, a former employee, from publicly discussing his conversations.

There is no basis for a court to make such a move to prevent Comey from coming before the panel to testify about President Trump’s efforts to get him to pull back on the FBI’s investigation of Russia’s hacking the 2016 presidential race. If the testimony involved classified information, there might be a colorable argument if the former employee agreed the conversation was confidential, and both thought it was covered by executive privilege and held the conversation on that basis, but absent even that dubious argument, conversations with the president of the United States do not give him the power to revoke the First Amendment. Nor do courts engage in prior restraint, enjoining speech before it has been made.

While the term “executive privilege” dates to the Eisenhower presidency, the concept of the executive branch withholding information from its constitutional co-equals goes back to the earliest days of our government. President George Washington convened his Cabinet to discuss and agree to withhold information about a military expedition from Congress. Thomas Jefferson’s notes from a Cabinet meeting show he discussed withholding information from Congress and the courts.

It was not until Richard Nixon withheld his secretly recorded conversations from the Watergate special prosecutor who had issued a grand jury subpoena did the US Supreme Court give executive privilege constitutional status based on the separation of powers of the branches. While the high court recognized the concept, it also recognized that President Nixon was using it to prevent the prosecutor from obtaining evidence of his criminal behavior. Nixon’s use of executive privilege during Watergate gave it a bad name, and subsequent presidents have invoked it only reluctantly.

No post-Watergate president used executive privilege more aggressively than Bill Clinton, when confronted with the most aggressive special prosecutor in American history, Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr. It is difficult to imagine any president wanting to silence a witness more than Clinton surely wished to quiet Monica Lewinsky. Yet unlike the Trump White House, the Clinton administration never pretended prohibiting her from testifying before a grand jury or Congress was possible. Before Trump, I have never even heard of a president seriously thinking he could silence someone with whom the president had conversed by invoking executive privilege.

Conspicuously absent from Huckabee Sanders’ announcement was any reference to the White House Counsel’s office, which surely knew the claim of privilege was nonexistent, and wanted nothing to do with the charade the communications team is playing with Comey. Now we will have to wait to see if any Trump apologists on the Senate Intelligence Committee are so foolish as to join the White House mini-sham.