Editor’s Note: Elisabeth Rosenthal is editor-in-chief of Kaiser Health News, an independent nonpartisan nonprofit newsroom focusing on health and health policy in Washington DC. She is a nonpracticing physician, former New York Times reporter, and the author of An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take It Back. The views expressed in this commentary are solely hers.

Story highlights

Elisabeth Rosenthal: It's not just that US health care is expensive, with prices tags often far higher than those in other developed countries

Americans face astronomical prices that quite simply defy the laws of economics, decency, and common sense, Rosenthal writes

When Jeffrey Kivi’s rheumatologist changed affiliations from one hospital in New York City to another, less than 20 blocks uptown, the price his insurer paid for the outpatient infusion he got about every 6 weeks to control his arthritis jumped from $19,000 to over $100,000. Same drug; same dose – though, Kivi noted, the pricier infusion room had free cookies, Wi-Fi and bottled water.

Mary Chapman, diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, started taking a then-new drug called Avonex in 1998, which belongs to a class of drugs called disease-modifying therapies. Approved in 1996, Avonex was expensive, about $9,000 a year. Today, two decades later, it’s no longer the latest thing – but its annual price tag is over $62,000.

Marvina White’s minor elective outpatient surgery to remove an annoying cyst on her hand was scheduled in 2014 based on her doctor’s availability. Because it was booked in a small facility that is formally classified as a hospital (with two operating rooms and 16 “spacious private suites”) rather than the outpatient surgery center where the doctor also practiced, the operating room fee was $11,000 rather than $2,000.

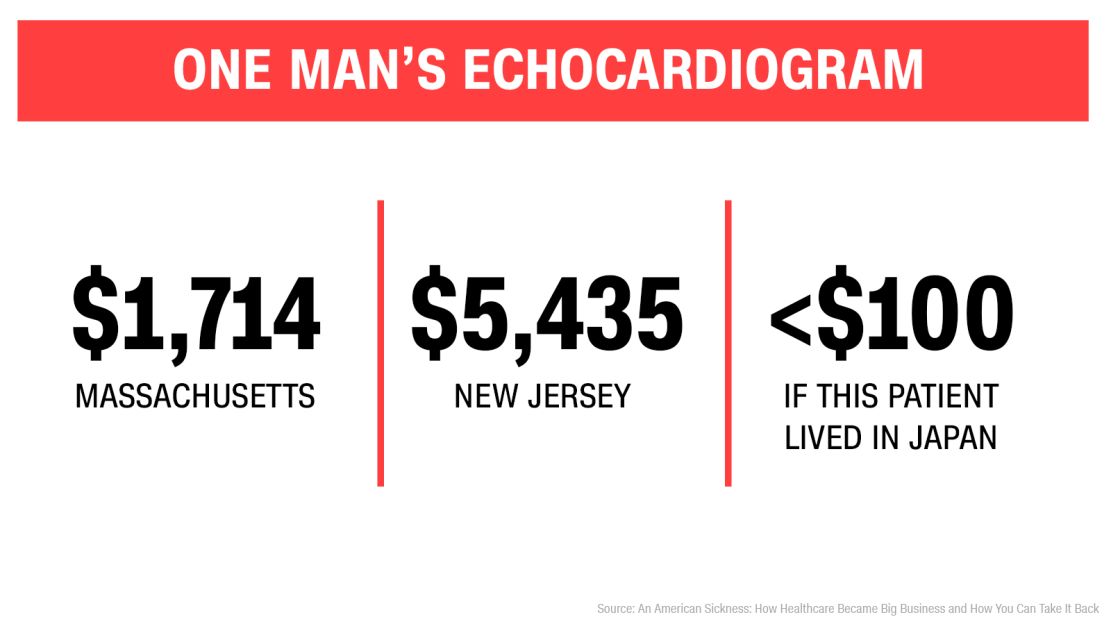

Len Charlap had two echocardiograms – sonograms of the heart – within a year: One, for $1,714, involved extensive testing at a Harvard training hospital; the other, for $5,435, was a far briefer exam at a community hospital in New Jersey.

It is not just that US healthcare is expensive, with price tags often far higher than those in other developed countries. We know that. At this point, Americans face astronomical prices that quite simply defy the laws of economics and – as each of the above patients noted when they contacted me – of decency and common sense.

‘The balance sheet just doesn’t work out’

“It’s the prices, stupid.”

This phrase, part of the title of a 2003 scholarly article in the journal Health Affairs explaining high US health expenditures, has been bandied about by a number of health economists for years.

But politicians have long been prone to ignore this essential wisdom. They do so today at their own peril. Outraged Americans at Town Hall meetings are wising up. Like patients who I’ve spoken to in my last few years of reporting, they have experienced the bankrupting and baffling illogic of US medical prices firsthand.

With the prices the US medical system demands for care, it’s no wonder that Republicans have had so much trouble finding a recipe to replace the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare, with “something better” for less money, as they’ve promised endlessly to do. Ironically, despite the extreme differences, the GOP is stumbling on the same underlying problem that ultimately tarnished the ACA in critics’ eyes: spiraling prices often necessitated skyrocketing premiums and deductibles, belying the “affordable” moniker. The balance sheet just doesn’t work out.

Any plan to solve America’s health care mess must confront this reality: Our prices for tests, drugs, hospitalizations and procedures – old or new – have gone up dramatically year by year, and are vastly higher than in other developed countries. Indeed, prices for similar interventions in other countries have often declined.

Why? The United States – more or less alone among developed countries – has no direct mechanism to rationalize prices for medical encounters, to insure they are at least nominally related to value. Worse still, we alone effectively allow businesses – mostly for-profit – to set the asking price. And, as these examples show, price and value have in many cases become completely uncoupled, allowing price to travel into the stratosphere.

The perils of ‘sticky pricing’

According to the rules of economics, the prices of innovative, breakthrough medical offerings should go down as they become more common. Competition should reduce prices as more manufacturers enter the field allowing purchaser-prescribers to choose from alternatives.

The pricing of pharmaceuticals and treatments in the United States often does exactly the opposite.

The United States suffers from a bizarre phenomenon economists call “sticky pricing,” where prices of competing medical services simply rise in tandem.

Though Mary Chapman’s original medicine, Avonex, was one of the first of a group of MS drugs called disease-modifying therapies, there are now many that neurologists may deploy. Every couple of years, a new medicine for MS comes onto the market, with a monthly price tag $1,000 or so higher than others – and all the drug companies making MS therapies raise their prices to that new sticky price ceiling. The result: multiple sclerosis drugs that sell for less than $1,000 per month in the UK now cost about $5,000 for Americans.

When one hospital system manages to get away with charging extremely high prices, it provides cover for others to raise theirs, even for treatments no longer considered particularly innovative, using technologies that have become commonplace. The last third of the 20th century, for example, saw the development of game-changing radiology machines – MRIs, CAT scans and sophisticated sonograms – that could plumb previously unseen depths of the body. But now they are decades old, their essential technology unchanged, despite refinements that are likely relevant in only a fraction of cases.

What if a test costs thousands where you live, but less than $100 somewhere else?

In Japan – where doctors, politicians and economists get together to decide what medical encounters are currently worth – the price of a novel technology must go down as it ages. That means that in Japan, Charlap’s exact echocardiogram at the time he had the tests went for under $100.

We can pay drastically higher prices depending on where a doctor decides to offer his services and how that facility sets its charges. That, in turn, often seems to turn more on amenities – free coffee and art – that it does on less tangible attributes, like the quality of care. Think how annoying it is when a hotel tacks on a $30 resort fee when you didn’t use the pool or the sauna. When you’re booked at a hospital for minor surgery, like White, or in a fancy infusion room, like Kivi (who has a Ph.D. in chemistry), the facility fee is thousands (sometimes tens of thousands) of dollars.

Health care facilities in the United States look like five-star hotels and sometimes employ curators, concierges and executives from the hospitality industry who talk about the “guest experience.” Even elite hospitals in other countries, which often charge a small fraction of the average $5,220 price of a US hospital day, tend to more resemble public high schools. At what price medical luxury?

Though they hold hearings and decry pricing, politicians from both parties have been mostly unwilling or unable to tackle this cost problem head on – likely because they hear (and benefit) far more from medical industry lobbyists than from patients. Even proposals that have garnered support from politicians in both parties, such as allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices, go nowhere.

Faced with prices that feel like extortion, sick patients like those above have few palatable options. In anger, Kivi switched to a drug that he could inject himself, though it didn’t work nearly as well. To afford her drug copayments, Chapman sold her car and her jewelry. Charlap was on Medicare, so it negotiated the price of his scan and paid far less.

When a biller told White prior to surgery that the facility charge would be $11,000 – she owed a 20% copayment – she canceled. Faced with extortion, she decided she’d prefer to live with a growth on her hand.

But some patients will choose another option, becoming what I call health care refugees. A few years ago, after a cancer scare made William Shelton, a school teacher in Oklahoma, more aware of America’s high prices, he picked up his family or four and moved to his wife’s birthplace, Brazil.