On Tuesday, former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak will appear in court – facing years in prison if convicted on corruption charges which seemed impossible less than a year ago.

The son and nephew of former prime ministers, scion of the Malay elite and head of the all-powerful United Malays National Organization (UMNO), which has dominated Malaysian politics since the country’s independence, Najib’s downfall is as staggering as the scale of the corruption he has been accused of.

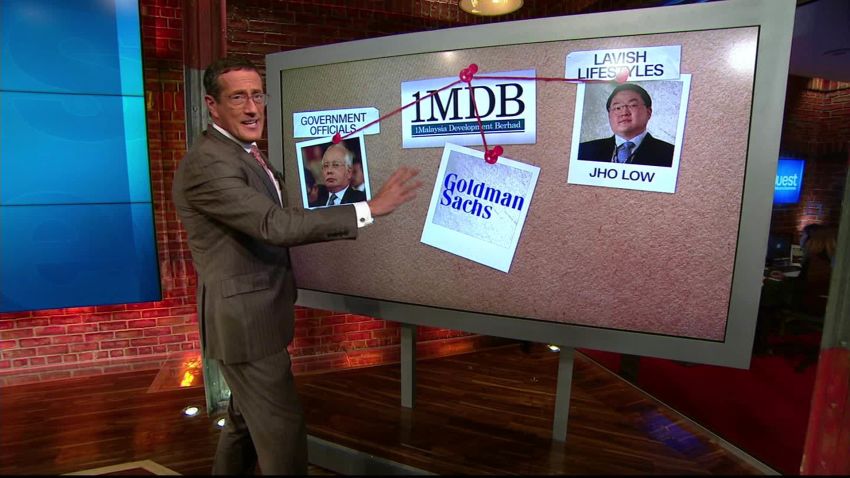

Even after the scandal over 1MDB – the sovereign wealth fund Najib set up and allegedly helped embezzle billions of dollars from – erupted worldwide, the idea of Malaysia prosecuting its former leader still seemed like fantasy. Najib was the “Teflon prime minister,” and almost all observers expected him to weather the storm.

Political son

Najib grew up surrounded by privilege and power. The son of Prime Minister Abdul Razak Hussein, he attended the elite Malvern College in the UK from the ages of 15 to 18 before going on to study economics at the University of Nottingham, an education which reportedly left him with a pronounced British accent some observers felt could hold him back in politics.

After a brief stint as an executive at the state-run oil company Petronas, Najib entered politics at just 23, taking over the Pekan parliamentary seat occupied by his father after the older man’s death in 1976. He quickly rose through the ranks of UMNO, the largest party in the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition set up by Abdul. Between 1976 and 1999, Najib held finance, culture, education and defense portfolios, overseeing in the latter role a significant investment in and modernization of Malaysia’s armed forces.

Najib proved an adept electoral operator, winning majorities of 23,000 and 26,000 in 2004 and 2008 respectively – among the highest margins in Malaysian history. In 2009, he succeeded Abdullah Ahmad Badawi as both UMNO leader and prime minister. While UMNO had previously succeeded in appealing to ethnic Malays, at the expense of Chinese and Indian voters, Najib emphasized a “multiracial, multi-religious” nation under the banner of 1Malaysia.

A key part of this approach was the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) sovereign wealth fund, which Najib and others said would be instrumental in “propelling Malaysia towards becoming a developed nation.”

However, according to prosecutors in Malaysia, the US and Singapore, 1MDB became a slush fund for executives including Najib, who allegedly used it to pay for his and his wife’s increasingly extravagant lifestyles as well as for vote-grabbing projects in parts of the country where UMNO support was flagging.

Scoops and scandal

In early 2015, journalists from the Sarawak Report and Wall Street Journal began reporting that millions of dollars had been siphoned off the fund after allegedly securing a series of leaked documents.

At first it seemed like the scandal might spell the end of Najib, as opponents – and even some within his party – demanded an investigation and called for him to resign.

Behind the scenes, there were efforts to smother the scandal. Xavier Justo, a former employee of the 1MDB-linked PetroSaudi, who allegedly attempted to blackmail that company with stolen documents before leaking them to journalists, was arrested in Thailand.

Facing years in a Thai jail, Justo was allegedly pressured to claim the Sarawak Report and The Edge, a Malaysian newspaper which had been leading the story domestically, of fabricating and doctoring the leaked documents.

Even as Najib denied any wrongdoing, the cascade of negative stories continued, and in July of that year he took to Facebook to defend himself.

“Let me be very clear: I have never taken funds for personal gain as alleged by my political opponents – whether from 1MDB, SRC International or other entities, as these companies have confirmed,” he wrote. “It is now clear that false allegations such as these are part of a concerted campaign of political sabotage to topple a democratically elected Prime Minister.”

Clare Rewcastle-Brown, of the Sarawak Report, said Malaysia had struggled for decades with corruption and entrenched privilege – but it allegedly all “got out of control under Najib.”

“It had been kind of contained under the strong rule of his predecessors,” she said.

Autocratic turn

In mid-2015, Attorney General Abdul Gani Patail informed police that investigators had enough information to prepare a charge sheet against Najib.

Yet Abdul Gani was later removed from his position for “health reasons” and replaced by a Najib ally who would later clear the Prime Minister of wrongdoing. Senior police and government officials involved in the investigation or critical of Najib were also replaced.

After Rewcastle-Brown secured the charge sheet and published it, Malaysia issued a warrant for her arrest. The reporter was accused of committing an act “detrimental to parliamentary democracy.”

“They thought that when I came out with the story originally at the start of 2015 that they could contain it,” Rewcastle-Brown said. “They created me into this sort of monstrous machine of forged documents and all the rest.”

While she was safe in the UK, journalists in Malaysia were more vulnerable. The Edge publisher Ho Kay Tat had already been arrested on sedition charges, and now the authorities moved to suspend the newspaper’s publication license altogether.

To clamp down on anti-government demonstrators, yellow clothing with the slogan “Bersih” – the word meaning “clean” used as the name for the protests – was banned.

Yet while he might have been able to contain anger on the streets, Najib had underestimated the frustrations bubbling up within the Malaysian state. According to Tom Wright and Bradley Hope, who reported on the case for the Wall Street Journal and wrote the book “Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World,” some officials feared Najib would shrug off the scandal.

“At the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, which had recommended the prime minister’s arrest, there was simmering anger over the mothballing of their investigation,” Wright and Hope wrote. “And so, a handful of investigators began to secretly feed information to the FBI.”

In July 2016, the US Justice Department stunned Malaysia by filing a suit to recover more than $1 billion in assets it said had been embezzled from 1MDB.

This was the “point of real no return (for Najib), although he probably didn’t see it,” Rewcastle-Brown said.

As prosecutors in the US chased assets and witnesses, 1MDB began to collapse under the weight of its massive borrowing. While Najib tried to win back favor following Donald Trump’s election, meeting the American leader in Washington in late 2017, it did not stop the Justice Department’s pursuit of him.

Najib, who had long courted Washington as a key ally, now turned to China. Chinese companies reportedly agreed to help bail out 1MDB, giving it a temporary reprieve, though some of the deals later fell through.

Election shock

Despite the negative headlines, lawsuits and alleged corruption, few counted Najib out as Malaysia entered the 2018 election.

The country’s opposition had never won an election. Its most dynamic politician, Anwar Ibrahim, was in jail on charges of sodomy, and while the various parties had formed a coalition led by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, he was 92 – and with a dubious history of his own.

The Malaysian electoral map was also heavily skewed in Najib’s favor, with some estimates saying his Barisan Nasional coalition could win a parliamentary majority with less than 20% of the popular vote.

Further, the government introduced a new law claiming to crack down on “fake news” which critics said was an attempt to criminalize criticism of Najib. Weeks before the poll, Mahathir’s party was dissolved for allegedly missing paperwork and he faced charges under the new “fake news” law.

“Malaysia was on the brink of utter catastrophe,” Rewcastle-Brown said. “He was running the economy into the ground and China’s hands, turning the place into a dictatorship. If he’d won that election it would have been the validation he was looking for.”

But she added that while “no one thought that this powerful grip he had on the country could be relinquished (the 2018 election) was the only chance Malaysians had.”

More than 76% of the 14.3 million eligible voters in the country turned out, with Mahathir’s opposition coalition taking 121 of 222 seats. Najib’s Barisan Nasional won just 79.

“We did not anticipate that the wave of change was … so convincing. That (Najib) had to acknowledge it and quit,” Anwar told CNN months after the election.

Downfall

Within days of the stunning election loss, Najib and his wife were barred from leaving the country. Police soon raided their properties and seized millions of dollars in luxury goods allegedly linked to the 1MDB funds.

In July 2018 – three years after the first 1MDB stories began emerging – Najib was charged with four counts of corruption. The charge sheet was later expanded to cover dozens of other alleged crimes.

His wife, Rosmah Mansour, whose profligate spending with funds allegedly embezzled from 1MDB had helped fuel public outrage, was arrested months later.

And this week, as Najib faces his accusers, many Malaysians hope the country will finally shed its old reputation and transform into an open democracy governed by the rule of law.

“I think the key people who are responsible must be held accountable,” Anwar said. “You must either accept this new regime of transparency and good governance, or you get out.”