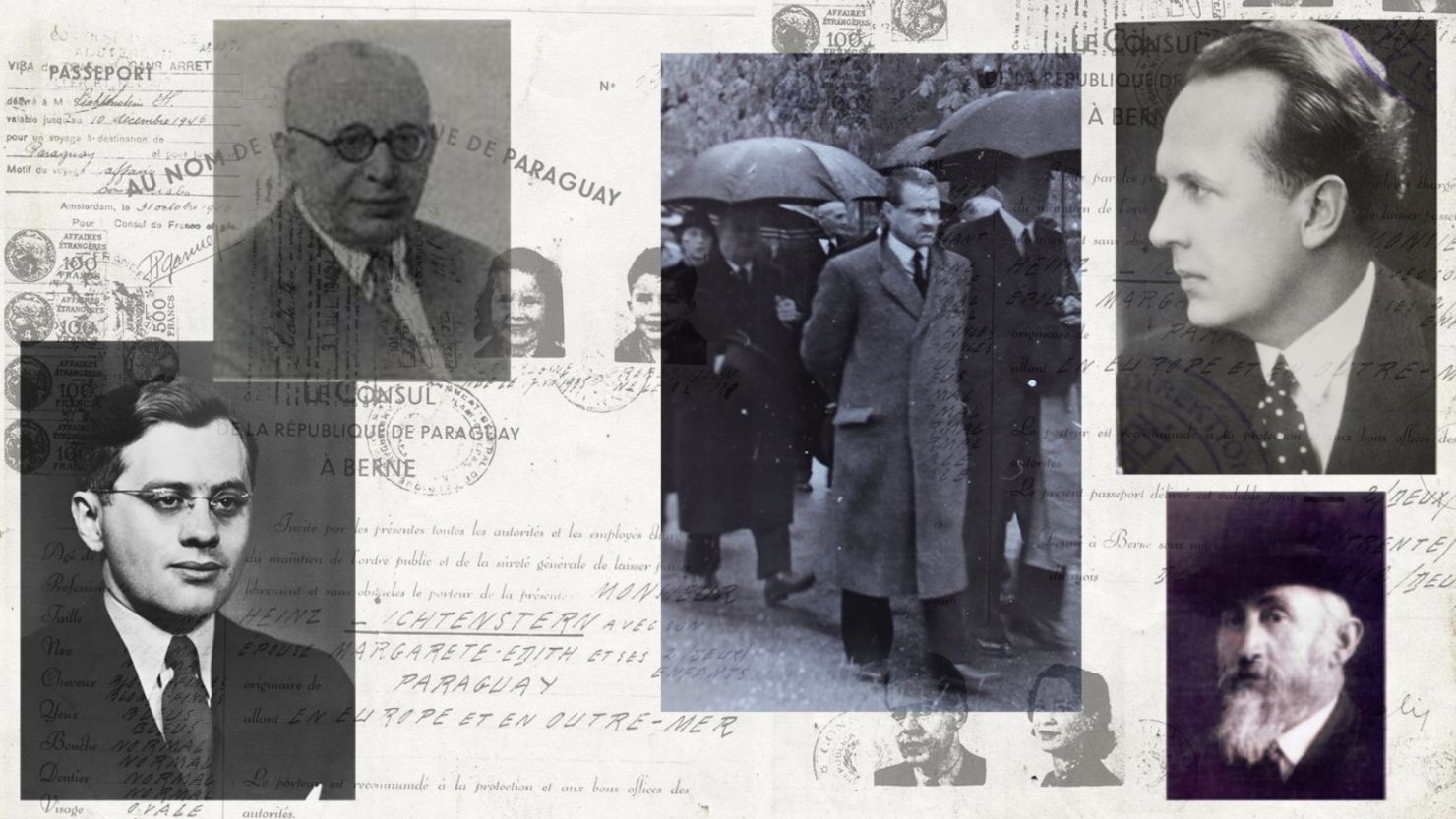

In 1942, two Jewish men were operating between the safety of neutral Switzerland and the danger of Nazi-occupied Europe. With coded messages they knew could be read by the Nazis, they smuggled the names and pictures of Jews hoping to escape death.

The destination of those names was the Polish Legation in Bern, where diplomats would bribe a counsel to Paraguay for blank passports and forge them under the nose of the Swiss government. The two men would then have to get those passports back to Jews in need of citizenship that would hopefully spare them from Germany’s death camps.

And in the shadows was Stefan Ryniewicz, deceiving authorities and convincing diplomats and police to ignore the life-saving, but illegal, scheme that could get them all classified as “persona non grata.”

It was a story Alexandra Van Ryn Reiter’s grandfather, Ryniewicz, never shared with her.

“Unfortunately, I wasn’t told anything at all,” she told CNN. “I just knew that my father’s side of the family was in Argentina and left Poland because of the war.”

Then last year, Reiter, who lives in Dallas, Georgia, received an international email.

Thinking it was a scam, she nearly deleted it – but luckily, she stopped to read it. It was from Jędrzej Uszyński, the first secretary of the Polish Embassy in Bern, Switzerland.

Uszyński asked about her grandfather and where he was buried. He wanted to know what happened to a hero.

He told her Ryniewicz was one of three Christian Polish diplomats that worked with at least three Jews in a secret organization the embassy called the Bernese group. Their plan was to forge Paraguayan passports for European Jews in hopes that they would be considered foreigners from neutral countries and avoid being sent to Nazi death camps, Uszyński said.

The stories of the members, and the potentially thousands of people who lived because of them, were made public in the past two years by archives documenting the actions of the Bernese group, according to the Polish Embassy. The archives are part of the ongoing efforts of historians and descendants alike to keep the stories of Holocaust survivors and the heroes of the Holocaust entrenched in the memories of those who survived them.

A newspaper in Georgia published Reiter’s story. The next day she was contacted by K. Heidi Fishman in Norwich, Vermont, who said her grandfather was part of the reason Fishman’s family was alive.

“It was surreal,” Reiter recalls. “I was talking to a direct descendant of one of these passport survivors. Any misstep, any small mistake and I would not be here nor Heidi.”

‘Don’t you have a Paraguayan passport? This is the time to use it.’

Fishman had grown up knowing her family had survived the Holocaust, and she knew that a Paraguayan passport had saved their lives. But she didn’t know how many people worked for that passport before it got to their hands.

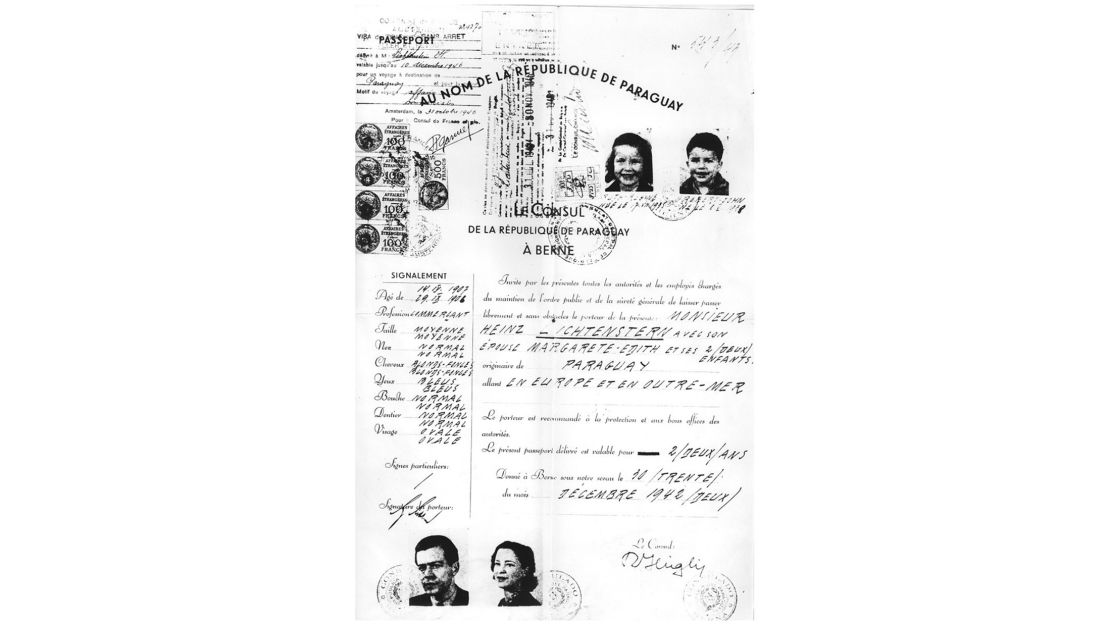

Her grandparents, Heinz and Margret Lichtenstern, moved their young children, Robert and Ruth, to Amsterdam from Germany as the family and the company Heinz worked for looked to evade the Nazis. When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Fishman said, the family gave their money to a friend to keep it out of Nazi hands and bribe someone for lifesaving documents.

At first, the family avoided being sent to a death camp because Heinz’s work in international metals trade appeared useful to the Nazis, Fishman said.

But ultimately, Heinz’s name appeared on the list for the next transport to Auschwitz.

At the last minute, as Fishman’s mother Ruth tells it, someone said “Hey, don’t you have the Paraguayan passport? This is the time to use it.”

The Nazi officers gave Heinz a small piece of paper with the word “withdrawn” and the family was sent to a ghetto camp for the rest of the war. There, people still risked death by malnutrition, but the family at least escaped the near certain death of Auschwitz.

When the war ended, the Lichtensterns were left stateless and could not return to their home in the Netherlands, Fishman said. They needed a passport to go back to their home and then to travel so Heinz could continue in his international trade.

The Paraguayan passport came in handy once again.

“So the passport saved them from going to Auschwitz, the passport got them back to Amsterdam, and the passport let them continue working to make money after the war when they had lost everything,” Fishman says.

How it worked: Courage. Expertise. Contacts.

Fishman’s family wasn’t alone, but the numbers of those who survived thanks to the passports forged by the Bernese group is one of the many questions still being investigated.

The embassy in Bern said they began telling the story of the Bernese group in 2017 using the personal files of Aleksander Ładoś, the Polish diplomat who headed the Polish Legation to Switzerland from 1940-1945. Then in 2018, the Polish Ministry of Culture acquired what is called the Eiss archive from the descendants of a member of the group, Chaim Eiss, according to Uszyński.

Uszyński, the first secretary of the Polish Embassy in Bern, told CNN that the embassy is in possession of about 3,000 falsified passports. His office estimates that they only have about 40% of the total.

Dr. Chaim Shalem is a historian who wrote “Rescue Endearvors of Chaim Yisrael Eiss,” published by Israel’s Holocaust museum. His estimate limits the passports sent out in Switzerland at 3,000.

Shalem also emphasized that Eiss was the catalyst of the Bernese group.

As the current Polish Ambassador to Switzerland, Jakub Kumoch explains each in the group had specific role. Eiss and Abraham Silberschein were Jewish activists who smuggled lists of people, descriptions and pictures from German-occupied territories to Ładoś’ office in Bern.

Ładoś’ Jewish consular clerk Juliusz Kuhl handled the bribes to an honorary counsel of Paraguay for blank passports, his consul Konstanty Rokicki forged them, and his deputy Stefan Ryniewicz convinced police and other diplomats to turn a blind eye to the ploy that violated both Swiss and international laws, Kumoch told CNN.

Eiss and Silberschien were the “engine of the operation,” Uszyński said, and it took the collaboration of “people who had courage, people who had expertise, and people who had contacts” to fund, obtain, forge and deliver the passports.

But the passport of a neutral nation was not a guarantee, and not all who obtained them survived.

‘Humanity against a backdrop of hate’

Poland has been wrestling with the part the Holocaust has played in shaping the nation’s historical legacy.

Last February, Polish President Andrzej Duda signed a controversial bill that would make it illegal to accuse the nation of complicity in crimes committed by Nazi Germany, including the Holocaust, and would ban terms such as “Polish death camps” in relation to Auschwitz and other similar camps located in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“The timing of the discovery is unfortunate as it is overshadowed by the recent politics,” Fishman says. “But that doesn’t take away from the need for people to understand that cooperating with people who are different is important. This is a story of cooperation and humanity against a backdrop of hate.”

And in recent years many places in Europe have seen a decline in Holocaust memory and a rise in anti-Semitism.

A CNN poll from November shows that about one European in 20 in the countries CNN surveyed has never heard of the Holocaust – those nations include France, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Germany, Great Britain and Sweden. In February, 80 graves in a Jewish cemetery in eastern France were desecrated with swastikas. Last year was a record high for the United Kingdom in anti-Semitic hate incidents, with more than 100 recorded every month of the year, according to the Community Security Trust.

‘If I don’t do it, who is going to?’

Reiter says she has been in contact with Fishman almost daily since they first connected in January. When they met face to face in April at Reiter’s Georgia home, she recalls that “it was like picking up with an old friend.”

They share a dedication to investigating and sharing a story that they see as demonstrating what can happen when individuals forgo their lines of division to save those in need.

“It’s amazing how many other people had to stick their necks out to save others,” Fishman says.

“I’m his granddaughter, and if I don’t do it who is going to?” Reiter says. “I think doing the right thing is important, and he must have known it was the right thing to do.”