Editor’s Note: CNN national security analyst John Kirby, a retired rear admiral in the US Navy, was a spokesman for both the State and Defense Departments in the Obama administration. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The old man said he didn’t do anything. I only half believed him.

People of his generation say that all the time, especially when they talk about their service.

That’s one of the reasons we call them the “Greatest Generation.” It’s not just because they won World War II. It’s because even in that most ultimate of victories, they remained humble.

Anyway, the old man kept saying it over and over. “I didn’t do anything. I didn’t do anything.”

And then he wept … openly, valiantly. And then he said it again. And I stood over him, all decked out in my dress blue uniform, ashamed for the first time to be wearing it. I’d been invited back to my hometown of St. Petersburg, Fla. in the spring of 2013 to give a speech, and I wanted to stop by the local veterans’ hospital to pay my respects.

But who in the hell was I to be in his presence? What could I possibly say to such a man?

Here he was, at the end of his life, dying – and ready to go, I might add – a hero, a man who landed at Anzio with the 179th regiment of the 45th Army Division.

A man who by his own account spent 91 consecutive days in combat.

A man who, along with his unit, pushed on past that deadly beachhead at Anzio in the winter of 1944 and eventually took Rome back from the Germans.

A man who proudly – no, reverently – showed me the picture of a beautiful young woman he knew he would marry before he even knew her name. And she was a beauty, too, let me tell you. Her name was Shirley, and she was a nurse.

I joked a little, asking how in the world a homely guy like him could score such a babe. The truth is, he was still a fine and handsome man, even as he lay in that hospital bed. The years had furrowed lines across his cheeks, but they hadn’t dimmed those blue eyes. They hadn’t stolen his charm.

He reminded me a little of screen legend Richard Widmark. A movie critic once called Widmark a man of “unconventional good looks,” who “boasted a chiseled face, all angles and shadows.”

That was the old man, too. The blond hair had grayed, but he still had a chiseled face.

There wasn’t any doubt in my mind how he won Shirley’s heart. He must have bowled her over.

Anyway, the old man shrugged and giggled and said as honestly as I think anyone could say that he had no idea how he won Shirley’s heart. He just knew she was the one. And he handed that little metal picture frame to me like it was gold … like it was her.

Here he was, a man – a dying man – whose proudest achievement in life, he told me, was the life he and that gorgeous young nurse gave their kids. He had helped set Italy free, helped free the world of Nazi tyranny, but the biggest legacy he believed he was leaving behind was his children.

There’s a lesson there, I reckon. Perhaps we ought not to strive for lives of success, but rather lives of value. And it has to start with what you actually do value. The old man valued love and loyalty and duty. He didn’t say that to me, of course. He wouldn’t stoop to say such a thing, not someone of his generation. Those things were simply expected. They were the norm. They were the things that got you through the sheer terror that was combat.

Anzio

“I didn’t do anything.”

Well, he survived Anzio, and that was surely something. If you haven’t read up on Anzio, you should. The battle was a bloodbath, “hell itself” according to one soldier in the old man’s regiment.

The whole idea was to conduct an amphibious landing on the Italian western shore, outflank German forces there and then attack Rome. The success of a landing at that location, in a basin that was basically reclaimed marshland and surrounded by mountains, depended on the element of surprise. Any delay at all would result in German occupation of the mountains and Allied entrapment down below.

And that’s exactly what happened.

Week after bloody week the German army pounded away at Allied troops stuck in the basin with nowhere to hide. The shelling and the bombing were relentless. It was said that any man who claimed he had been around Anzio two days without having a shell hit within 100 yards of him was just bragging.

“Sometimes you hear the shell whine after you’ve heard it explode; sometimes you hear it whine and it never explodes,” wrote Ernie Pyle of the battle. “But I’ve found out one thing here that’s just the same as anywhere else, and that’s that old weakness in the joints when they get to landing close … your elbows get flabby and you breathe in little short jerks, and your chest feels empty, and you’re too excited to do anything but hope.”

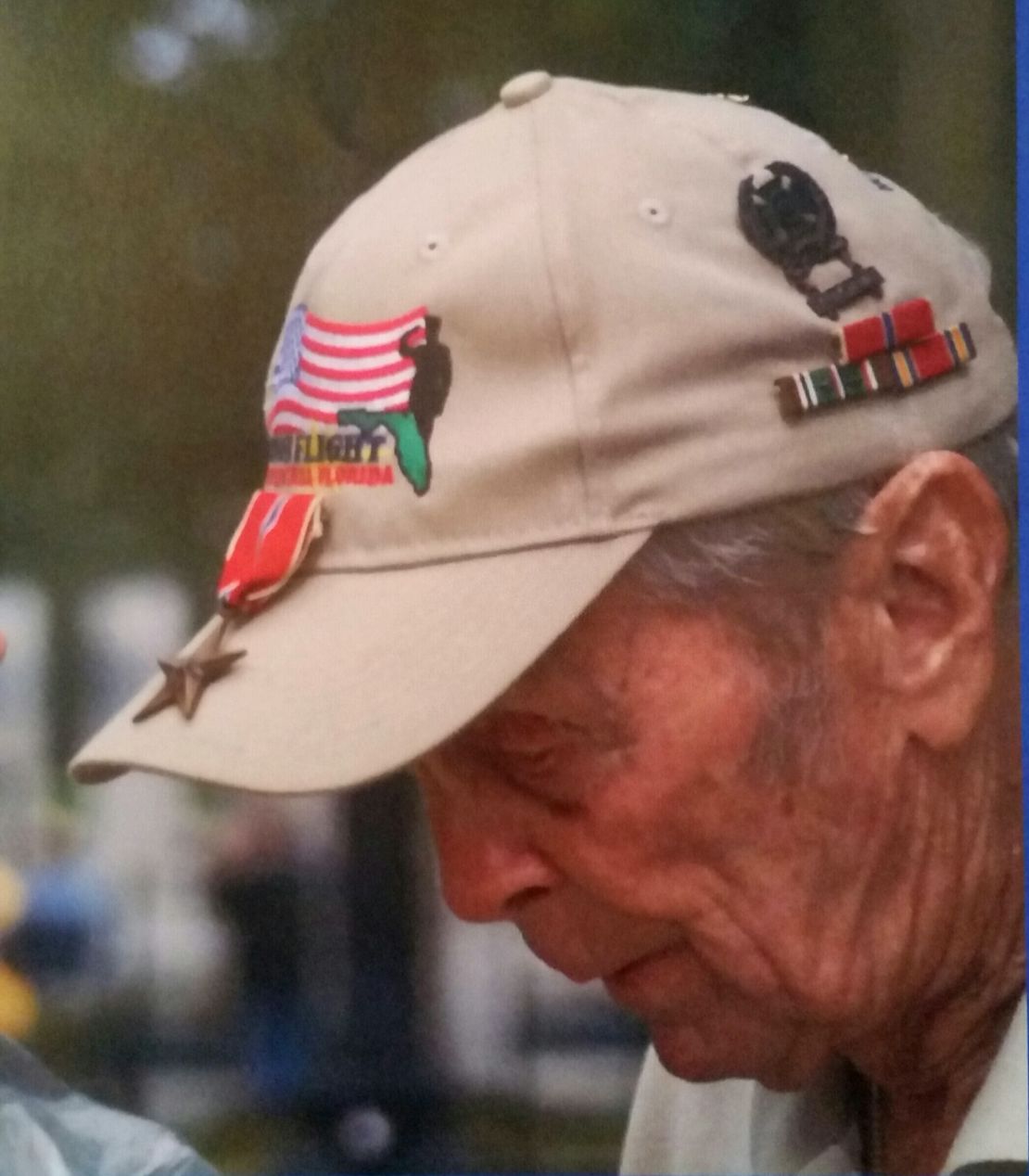

I’m certain there were many days and nights and in-betweens when Charles Nease, Private, U.S. Army, was too excited to do anything but hope. My guess is that he simply willed himself onward, driven not by some sort of superhuman courage but by the fear of letting down his buddies, of failing in his duty. I can’t imagine that he ever did fail, though.

A disappearing generation

Charlie Nease died a few days after I visited with him in the hospital back in 2013. He was 87 years old. His children were there to see him off before he met back up with Shirley, the only nurse he really wanted to see.

We’re losing World War II veterans at a pretty fast clip these days. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, fewer than 500,000 of the 16 million Americans who served during the war were alive in 2018.

Next month sees us commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Normandy landings. So, it’s important for us to remember them and their stories. It’s important for us to put a human face on history, to remember that once, a long time ago, they were young and scared and brave and in love.

I know Memorial Day honors those who were killed on the battlefield. And Private Nease surely wasn’t, though many of his friends surely were. And yet, right around this time of year, I can’t help but think about him. The more I do, the more I think he was right after all. He didn’t do anything. He did everything, everything a man could hope to do with his life and still call himself a man.

And we are all richer, whether we know it or not – whether we choose to appreciate it or not – for having had people like him walk the earth. That’s seems one hell of a memorial to me.