The tall-ship crew enjoyed a life of adventure -- until the Bounty went down in Hurricane Sandy. Two deaths in the disaster have sparked an inquiry. Among the questions: Did the crew mistakenly put its trust in the hands of a risk-taking captain?

The Bounty departed New London, Connecticut, on October 25 for a voyage to St. Petersburg, Florida, that was expected to take two weeks. The plan was to sail wide to the east and south as fast as possible around the Florida Keys to avoid Hurricane Sandy.

Alberto Mier/CNN

Before dawn, October 29, 2012

Rain hammered the ceiling, and they could hear the wail of hurricane winds. Below them, the engine room was at least waist-high in seawater. Their ship was without power, its engines and generators dead.

It was a few hours before sunrise, Monday, October 29, 2012, and the magnificent three-masted wooden square-rigger HMS Bounty was losing its battle with Hurricane Sandy.

The captain, Robin Walbridge, wanted answers.

What went wrong?

At what point did we lose control?

Gathered in the ship's navigation shack and exhausted from struggling for more than a day to keep water out of the leaking boat, none of the crew had answers.

They all knew: The Bounty was going down.

For eight days last month, the U.S. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board held hearings on the sinking of the Bounty. The agencies posed the same question Walbridge asked in the eleventh hour: What went wrong?

And another: Why?

Why did none of the crew publicly question the captain when he chose to sail toward a hurricane? Why weren't the pumps examined more closely before the Bounty got under way? Why did the ship leak so badly so soon after it had been repaired?

Why did two people die?

Investigators probed for human motive and error as they questioned the witnesses, including surviving crew members. The aim: to determine responsibility, culpability and possible negligence.

The outcome of the inquiry won't be known at least until the end of the year -- the earliest the NTSB and Coast Guard expect to issue their reports. But plenty about the Bounty and its last days has already emerged. This story is based on testimony at the hearings, as well as interviews with survivors. The Bounty's owner declined to testify or discuss with CNN the allegations made by witnesses and former crew members.

The hearings focused on the Bounty's seaworthiness and on its seasoned captain, who commanded a nascent crew. Ten of Bounty's 15 crew members had been aboard for less than a year – including two who'd joined less than a month before its last voyage.

Crew members testified that the word in the tall-ship community was that the Bounty suffered from shoddy maintenance and spotty training. But some believed the vessel's reputation was turning around. Extensive repairs had been made twice in the past decade and some work had been done weeks earlier.

But the way it was licensed, Bounty wasn't subject to tough Coast Guard inspections or mandatory repairs. Crew members didn't seem to care. They flocked to the ship anyway – to the opportunity to learn seamanship skills from a captain they revered. A man who, by his own admission, was unafraid of sailing through hurricanes.

They trusted the skipper almost without question.

By the time they'd sailed into the path of Hurricane Sandy, the crew was already a family of sorts, bound by a thirst for adventure – and a life built around a stiff wind and open water.

But the ship itself didn't prove to be as tightly knit as its crew.

During the boat's final hours, Bounty turned into a crucible that tested them beyond their experience.

By the time it was over, the disaster had changed them all. It shifted their perspectives on danger, caution and risk – in surprising ways.

The HMS Bounty, seen here in 2010 in Cleveland, sailed around the world as a tourist attraction vessel. Because of how it was licensed, the ship wasn’t subject to tough Coast Guard inspections.

The Plain Dealer/Landov

Late afternoon, Thursday, October 25

Walbridge scanned the faces of his crew members as they stood on deck at the ship's berth in New London, Connecticut.

It was an all-hands meeting at the capstan, a spool-shaped piece of equipment that sits near the helm – a place made sacred by its role as a gathering place for the Bounty family. In just a few hours, the vessel was scheduled to set sail for St. Petersburg, Florida, where it would host tours for paying customers.

St. Petersburg was also home for Bounty's captain, a lifelong sailor with a weathered face, hearing aids and thinning gray hair he often tied back in a tiny ponytail. There, he shared a comfy 1930s home with his wife, whom he fondly called Miss Claudia. She hadn't seen her wandering sailor for a month. But it was Walbridge's 63rd birthday, and the couple had spoken via Skype that morning. They were both eager for a reunion. Between them loomed Hurricane Sandy.

The skies over Connecticut were mostly clear, with light winds and temperatures in the high 50s. But the Internet was already screaming warnings about the storm, located about 125 miles east-southeast of Nassau, Bahamas. Forecasters predicted Sandy would grow larger in the next couple of days and zigzag northwest, then north-northeast, up along the Eastern Seaboard.

Walbridge knew there was concern among his crew. Worried friends and family had called and texted. First mate John Svendsen would later say he privately urged Walbridge to delay the trip – to stay in New London or head to an out-of-the-way port. So the captain, with 17 years at Bounty's helm, called the crew together.

Meetings around the capstan traditionally allowed for give and take between commander and crew. This time, Walbridge didn't invite discussion. Instead, he did all the talking.

Describing Sandy, Walbridge used the word "Frankenstorm," by one account, a reference to the media frenzy surrounding the hurricane. He described its predicted path and, as another shipmate put it, his "plan of attack" aimed at harnessing the storm's winds to increase Bounty's speed.

Ships are safer at sea during hurricanes, Walbridge said. I've sailed into hurricanes before.

Next, Walbridge revealed the bottom line: Anyone who wants to abandon the voyage has the option to do so, he said. The commander made it clear there would be no hard feelings.

There was no mention of future employment on the Bounty for departing crew, the third mate testified, nor did the captain offer to pay expenses home.

Any takers? No hands went up.

And no one at the meeting -- including the first mate – voiced any worries about the journey.

On this day, there was no mutiny on the Bounty. Its crew members put their faith in the captain.

They ranged in age from 20 to 66.

Four had been on the Bounty only a few months. Others, a few years. For the engineer and the cook, it was their maiden voyage.

Landing a job on a traditionally rigged wooden tall ship isn't easy. U.S. vessels number in the mere dozens. The Bounty crew members were typical of those who compete for the coveted spots. Many grow up in coastal towns with proud sailing traditions. Some are students or retired naval enthusiasts or Maine schooner bums. Or even middle-aged women who play Mama Bear to a boatload of ocean nomads.

Robin Walbridge, Bounty's captain for 17 years, chose to leave port in Connecticut with a crew of 15 and sail toward Sandy, one of the worst hurricanes in recent memory.

Dave Souza/Herald News

Boarding Bounty for the first time – as a tourist – was all it took to make 20-year-old Anna Sprague yearn for that life. The Auburn University journalism major inherited her love for sailing from her father and nurtured it by competing on the school sailing team. But it was at a festival in her hometown of Savannah, Georgia, last May that she caught the tall-ship bug.

From the moment her feet touched the deck she made up her mind to sign on. She knew that winning a job on a tall ship could open doors to her dream: adventure combined with constant travel.

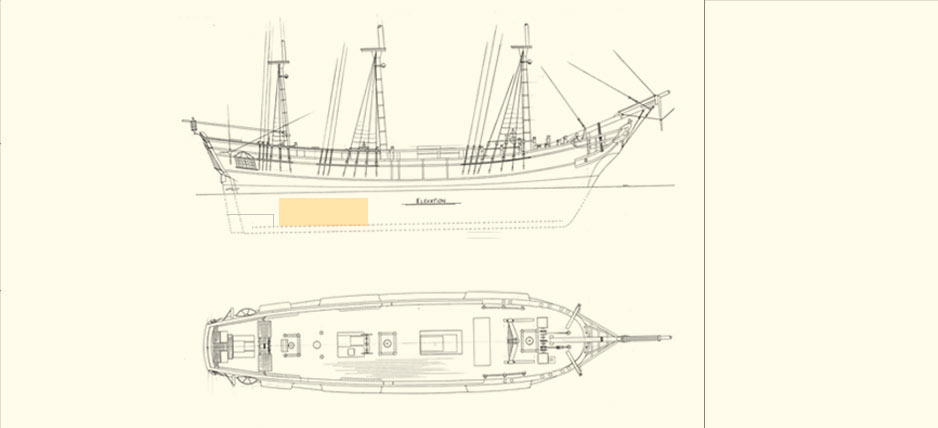

Sprague explored Bounty's 180 feet of oak and Douglas fir. Her eyes followed the lines of its three wooden masts stretching a hundred feet into the sky. Every part of the ship, she knew, served a unique purpose, including its 100-plus rope lines and complicated rigging.

With her trademark drive and confidence, Sprague marched up to a crew member and asked, "How can I be you?"

Later that day, she encountered John Svendsen who, as first mate, was second in command. At 41, with hair reaching down to the middle of his back, Svendsen had spent most of his life on the ocean, logging time as a diving teacher and boat captain. He'd joined the Bounty in February 2010.

Confronted with Sprague's enthusiasm and confidence, Svendsen offered her a chance to volunteer as a deckhand. A few months later, she'd earned a paid gig.

She was in.

Like Sprague, Claudene Christian, 42, signed on to the Bounty last May. And like Sprague, she'd never before worked on a tall ship.

Christian had lived in places as diverse as Alaska, Los Angeles, and Oklahoma. Never afraid to try new things, she'd competed in beauty pageants and cheered for the University of Southern California as one of its Song Girls. Christian seemed to like shifting gears in life. She launched a doll-making company. At one point, she co-owned a bar in L.A.

The idea of crewing on a tall ship dawned on her after she visited a replica of Christopher Columbus' famous wooden vessel the Nina. She seemed destined to join the Bounty, if for no other reason than her DNA: Christian claimed to be a descendent of Fletcher Christian – a mutineer on the original Bounty centuries ago.

The replica of the Bounty had a history of its own rooted in the 1962 MGM film "Mutiny on the Bounty," starring Marlon Brando. Unlike the 18th century version, this ship had two engines to propel it in addition to its sails. The boat was bigger than its namesake in order to accommodate a film crew and fuel tanks required to sail to the remote South Pacific.

It was never supposed to last 50 years. In fact, the plan was to destroy it.

Igniting the Bounty and turning it into a floating inferno surely would have created a spectacular movie image. But Brando said no. The ship was too good to burn. MGM acquiesced.

Over the decades, ownership of the Bounty passed to billionaire Ted Turner, who eventually donated it to the Fall River Chamber Foundation in Massachusetts as an educational vessel. It was overhauled in 2001 and again in 2006. Now it belonged to the New York-based HMS Bounty Organization, which sailed it from port to port as a tourist attraction. The ship wasn't licensed to carry passengers out to sea.

In the weeks before the Bounty left New London, Christian, Sprague and other crew members spent time maintaining its hull. Wooden vessels need special care to protect them from tiny waterborne organisms that eat away at the ship. Rotted planks must be replaced. Cracks and open seams are plugged with special materials. At the half-century mark, the Bounty was expected to leak a little. Rough seas could make it worse.

Though Christian had no tall ship sailing experience, crewmates warmed to her upbeat personality. And it didn't take long for Christian to grow attached to her colleagues. She doted on some like a mother.

Christian and Sprague had joined a band of sailors with different backgrounds and personalities, but they shared the same desire: to see the world as ancient mariners did, when Columbus, da Gama and Magellan were reshaping the Earth from flat to round.

Left: A sailor steers the ship in 2010. Bounty’s crew was a family of sorts, bound by a thirst for adventure – and a life built around a stiff wind and open water.

Right: Every part of a traditionally rigged sailing ship serves a unique purpose, including its 100-plus rope lines. Bounty shipmates hoist a sail in 2010.

The Plain Dealer/Landov

Adam Prokosh, 27, was an earnest, thoughtful five-year veteran of tall ships who'd been on board for eight months. He hoped to captain his own vessel someday.

Deckhand Jessica Hewitt -- a trusting, strong-willed 25-year-old and a licensed graduate of the prestigious Maine Maritime Academy -- had a big smile and a bright attitude.

Another MMA grad, 37-year old Matt Sanders, was the second mate. The tall, broad-shouldered and square-jawed sailor had never served aboard a wooden tall ship.

Ship engineer Chris Barksdale, 56, and cook Jessica Black, 34, were Bounty's newest crew members, coming on board within a month before the ship set sail from Connecticut.

Mark Warner, 33, was a bright deckhand who'd joined the crew the previous May. He came with experience: Bounty was his fourth tall ship.

Deckhand John D. Jones ![]() , 29, was a tall-ship first-timer from St. Augustine, Florida, who'd never before worked aboard a wooden vessel.

, 29, was a tall-ship first-timer from St. Augustine, Florida, who'd never before worked aboard a wooden vessel.

Drew Salapatek, 29, hailed from Blue Island, Illinois. With long blond hair and a beard, Salapatek had a gentle way about him and a great deal of respect for Walbridge.

Laura Groves, 28, was a three-year Bounty veteran. She held the rank of bosun – the ship's taskmistress in charge of assigning and prioritizing duties. With dark hair and glasses, she was short in stature but towering with confidence.

Doug Faunt, 66, had been with the Bounty for five seasons as its volunteer electrician. After two decades working at IT giant Cisco Systems, he could afford to follow his tall ship passion without getting paid. The wiry, balding, white-bearded resident of Oakland, California, possessed valuable knowledge about computers, engines and communications equipment.

He also had a sensitive side. He brought his prized teddy bear onboard and took some shipmates under his wing, including Christian and another deckhand named Josh Scornavacchi.

Scornavacchi, 25, gave off the quiet, intense vibe of an old soul. Born with the heart of an explorer, the Eastern Pennsylvania resident came to the Bounty with a dream of one day circumnavigating the globe.

They all came to work for Walbridge, a Vermont native who'd borrowed a sailboat at age 18 and discovered his passion. He worked his way from houseboat field mechanic on Florida's Suwannee River to Massachusetts, where he trained crew for the Navy tall ship USS Constitution.

In 1995, he took command as Bounty's captain -- and teacher to a host of sailors who Walbridge liked to brag were the "future captains of America."

For new crew, basic ship training included a safety tour and lessons on how to don emergency immersion gear called Gumby suits. Later, they would learn how to climb the masts to tend the sails -- "going aloft," as it's known.

The captain sometimes quizzed his crew on how to maneuver the ship under various circumstances. It was his way of keeping them thinking about the big picture -- how their roles came together to sail the boat.

His recipe for bonding with his shipmates was as simple as spaghetti. He'd boil up a batch and invite them to eat and shoot the breeze. With each spaghetti supper, the Bounty crew bonded a little tighter as a loyal family.

In small ways, Walbridge revealed his personal side. The captain practiced seafaring superstitions: Pots and pans were to be hung in the galley in the direction in which they could catch the prevailing winds. And he had his own language of sorts – what the crew called "Robin-isms." "Wakey, wakey little guppies," or "Wakey, wakey little snakies," he would say to rouse sleeping mates.

Work rotations were eight hours on, eight hours off. Some shipmates found time for a game of Twister or an electric guitar jam session. They challenged each other to jump off the Bounty in every port. On clear nights, experienced sailors turned off the GPS and steered the old-fashioned way: with nothing but a compass and the stars.

Canoodling on the boat was common. Some crew worried the captain would crack down on shipboard romances.

That fear loomed large one day when Walbridge called a meeting. The subject, he announced: reproduction. What would he say? As they gathered to listen, shipmates shot each other worried glances.

We have a big problem on the boat, the captain said, wearing a stern face.

Then he broke into a smile. A bike had "reproduced" from one to two, he said. He asked his crew to limit the number of bikes on board.

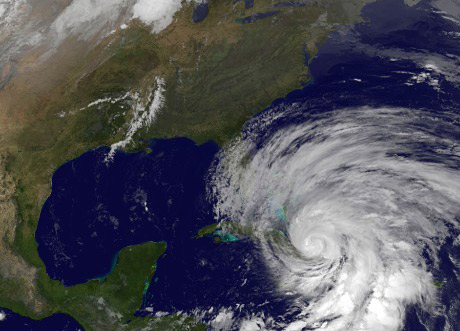

Left: As Bounty left Connecticut for what was expected to be a two-week voyage to St. Petersburg, Florida, Hurricane Sandy was kicking up a fuss over the Bahamas.

Right: On the day the Bounty sank, Hurricane Sandy was growing into one of the largest storms on record – eventually spanning more than 900 miles.

NOAA/NASA

Early evening, Thursday, October 25

OK, we're going to get under way, Walbridge ordered. Cast off lines.

With that command, the Bounty began its journey toward the hurricane.

It was a gorgeous Thursday evening with no sign of Sandy kicking up a fuss near the Bahamas, a thousand miles to the south. But deckhands got busy securing gear; rougher seas were sure to come.

With both engines up and running, the captain ordered the Bounty to "make tracks" to the southeast. The mates knew he wanted to go as far south as possible -- as fast as possible.

The plan was to swing out wide.

By sailing east of Sandy, they would put some room between the ship and the hurricane, then cut back west toward Key West, Florida, and around to Florida's west coast and St. Petersburg.

As Bounty sailed past the eastern tip of New York's Long Island on Thursday night, water in the bilge area -- at the bottom of the boat, below the water line -- appeared to be at routine levels.

The bilge is designed to hold water that routinely finds its way aboard a ship from rain, rough seas and small leaks. Electric pumps in the engine room, just above the bilge, eject the water back into the sea. Bounty's pumps didn't seem to be performing at their usual speed, but the crew was not alarmed.

The engine room itself worried Bounty's newly hired engineer, Chris Barksdale. He thought it needed a good cleaning. Sawdust and wood chips littered the floor. Everything just looked old.

Before arriving in Connecticut, the vessel had undergone repairs at a shipyard in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. Rot infested 18-foot wooden planks on Bounty's forward right and left sides. Workers replaced them and caulked cracks and gaps in the ship's hull below the waterline.

Walbridge was warned by the shipyard that some of the boat's frames – its ribs -- also contained rot, multiple witnesses testified. The shipyard manager testified that the captain said he'd do the repairs later.

Around 9:30 a.m. on Saturday, October 27, about 300 miles east of Virginia Beach, Virginia, the captain made his move: Instead of continuing with his original plan to stay east of the storm, he ordered the crew to change course. He wanted to pilot the ship northwest of Sandy to harness its winds. Turning more westerly, the boat crossed the path of the oncoming hurricane.

By then Sandy churned about 600 miles away. Eventually, it would grow into one of the largest hurricanes on record to hit the East Coast, spanning more than 900 miles.

Most of the crew had never sailed through a dangerous storm. The work can grind down even the hale and hearty. It makes simple shipboard tasks like walking -- and sleeping and eating – difficult if not impossible.

The winds stiffened and Bounty's sailors took notice. The ride turned rougher as higher waves rocked the boat.

Water crept out of the bilge area -- and up into the engine room.

This wasn't the captain's first hurricane.

"There's no such thing as bad weather," he said just weeks before setting sail toward Sandy. "There's just different kinds of weather."

In a video that would eventually find its way to YouTube, he explained how to "get a good ride" out of a hurricane, by sailing "as close to the eye of it as you can" and staying behind the storm in its southeast quadrant.

"We chase hurricanes," Walbridge said, smiling.

His sailors followed Bounty’s captain, Robin Walbridge, with almost unquestioning loyalty. But former crew members said he was a brilliant chess master at finding ways to get around the rules.

Courtesy Walbridge Family

The captain's third in command on this voyage, Dan Cleveland, 25, was a graduate of the Walbridge school of hurricane sailing.

The tall, likable former landscaper with a boyish, bearded face and a calming baritone voice joined the Bounty in 2008, his first tall ship job. Later that year, Walbridge conducted a lesson in hurricane navigation by charting a course right behind a storm off Central America.

You don't want to be in its path, Walbridge taught Cleveland, but finding a safe place behind the storm is OK. As the ship closed in on the eye, the captain backed off – fearing its destructive power.

But not everyone was willing to sail the Walbridge way.

Two former Bounty crew members contacted by CNN portrayed the captain as a man who played fast and loose with the rules; a poor leader with an unpredictable command style, who was dismissive of protocol.

Just as Walbridge chose to set sail toward Hurricane Sandy, on other voyages he often made decisions about courses and destinations without consulting the crew, said Sarah Nelson, who served under Walbridge for nine months in 2007. The Bounty was Nelson's third tall ship; she is now a licensed captain.

When Nelson told friends she was joining the Bounty, they paused and took a deep breath. Not a good idea, they said. The boat was falling apart. But the Bounty was being overhauled at a shipyard, she responded. She was willing to suspend her doubts.

Her experience on the ship, however, confirmed her fears. She said that the Bounty operated in a gray area where the rules were vague and clever workarounds could save time, effort and money.

She witnessed the vessel appearing to violate maritime traffic rules while navigating the crowded Strait of Gibraltar.

She saw holes in one of the ship's masts. She reported it, she said, but nothing was done, and she felt unsafe.

Eventually, she reached her limit -- quitting in protest during the middle of a voyage.

Testimony confirmed at least one of Nelson's complaints: The mast on the Bounty was later replaced.

Another licensed captain and ex-Bounty crew member, Samantha Dinsmore, agrees with Nelson: Walbridge wasn't the best captain to work for, she said. He looked for easy solutions to potentially expensive problems like ship repairs, she said, and was a brilliant chess master at finding ways to get around the rules.

Occasionally he could be stubborn, said Dinsmore. And when sailors were on deck, they did what they were told.

John Svendsen, who'd worked with Walbridge for more than two years and was his first mate on Bounty's last voyage, said the captain could be "very firm in his ideas." But he never saw him seek out a storm. The Bounty, he said, wasn't chasing Hurricane Sandy.

Still, Nelson and Dinsmore said they weren't surprised to hear last October that the Bounty was in trouble.

Sunday, October 28

A day after the change of course ordered by Walbridge, Bounty was less than 200 miles from the eye of the storm. The crew estimated winds at 70 mph and the seas at 25 feet. It took two people to guide Bounty's helm.

Above deck, the wind sliced a huge lower sail in half on the forward mast. Another wayward sail nearly injured as he fought to control it.

Below deck, crew members suffered from seasickness. In the galley, the motion pulled tables from their hinges.

But the high-stakes battle played out in the engine room.

Fighting rising water in the ungodly hot compartment, second mate Matt Sanders ![]() frantically opened and closed a series of valves that pumped water from different areas of the ship.

frantically opened and closed a series of valves that pumped water from different areas of the ship.

All the while, he kept an eye on the boat's critical generators and engines to make sure they remained dry. As the day wore on, desperation rose with the water level -- from ankle-deep to knee-deep.

The pumps were vital to saving the ship. But debris was killing the pumps.

Wood chips and sawdust from the dirty floor were floating in the rising water and clogging the pumps. They had to be shut off constantly to clear the strainers. Scornavacchi and Adam Prokosh ![]() used trash bags – and their bare hands – to scoop debris.

used trash bags – and their bare hands – to scoop debris.

In its own way, the Bounty fought against the storm, too. The pounding of the hull against the ocean sounded to engineer Chris Barksdale ![]() like a "couple of thousand pieces of wood rubbing up against each other."

like a "couple of thousand pieces of wood rubbing up against each other."

One violent roll tossed the seasick Barksdale across the engine room -- gashing his arm. Another sent the captain flying into a table, injuring his back. Yet another slammed Prokosh, fetching a colander from the ship's galley to strain debris, into a wall, injuring a vertebra, cracking three ribs and separating a shoulder.

Claudene Christian ![]() put Prokosh on a mattress and made sure he was as comfortable as possible.

put Prokosh on a mattress and made sure he was as comfortable as possible.

At 4 p.m., by most accounts, 4 feet of seawater covered the engine room. Electrical equipment snapped and popped, short-circuiting in the water. Walbridge admitted what they all feared: They were losing the battle.

As the scramble to pump water off the ship grew more desperate, deckhand Mark Warner ![]() smashed the engine room door open so he could move a portable gasoline powered pump up to the deck.

smashed the engine room door open so he could move a portable gasoline powered pump up to the deck.

But the pump wouldn't work. According to testimony, no one had been trained to use it.

Around 7 p.m., one of the ship's two generators failed.

By 8 p.m. the crew started gathering emergency supplies – food rations, drinking water, lifejackets, even diving masks -- in case they had to abandon ship. Jessica Hewitt ![]() turned to Drew Salapatek

turned to Drew Salapatek ![]() . If the ship goes down, she said, don't lose me.

. If the ship goes down, she said, don't lose me.

Efforts to alert the Coast Guard became an exercise in trial and error.

The ship's high frequency radio: no response.

Bounty's satellite phone: no response.

Finally, electrician Doug Faunt ![]() rigged a ham radio to send and receive e-mail. They e-mailed Bounty's home office, which in turn contacted the Coast Guard at 9 p.m. The crew learned a Coast Guard C-130 search aircraft was heading toward the Bounty.

rigged a ham radio to send and receive e-mail. They e-mailed Bounty's home office, which in turn contacted the Coast Guard at 9 p.m. The crew learned a Coast Guard C-130 search aircraft was heading toward the Bounty.

About an hour later, the second generator died, plunging the boat into darkness.

Sometime after midnight, Walbridge called the crew together in the navigation shack. By then, his question – What went wrong? – must have seemed like a moot point. They were exhausted after their losing battle. They needed to focus on how they were going to safely abandon ship.

Water in the engine room measured more than 6 feet deep.

It's not known why the Bounty's captain changed his plans to sail around the east side of the hurricane. Instead, the ship crossed in front of the storm, eventually sinking on October 29.

Alberto Mier/CNN

With the engines dead, Bounty was at the mercy of the forces of nature 100 miles off North Carolina -- in wind gusts estimated at 100 mph and seas as high as 30 feet.

Walbridge said the Coast Guard planned to launch rescue helicopters around 6 a.m., weather permitting. If they could hold off abandoning ship, he told the crew, perhaps they wouldn't be in the water too long.

He ordered the crew to don their emergency Gumby suits.

Warner and Anna Sprague ![]() helped shipmates -- including the seriously injured Walbridge -- put on the bulky, buoyant suits. Warner could tell the captain was in pain.

helped shipmates -- including the seriously injured Walbridge -- put on the bulky, buoyant suits. Warner could tell the captain was in pain.

Sandy wouldn't relent to Walbridge's plan to hold off until daylight. When seawater began flooding the "tween" deck above the engine room around 4 a.m., the captain decided it was time to go.

Third mate Dan Cleveland ![]() and bosun Laura Groves

and bosun Laura Groves ![]() helped each crew member climb up on the ship's top deck. Standing near the capstan, they directed shipmates to move carefully toward the back of the pitching boat. Hold on to each other, they commanded, stay low against the wind and rain.

helped each crew member climb up on the ship's top deck. Standing near the capstan, they directed shipmates to move carefully toward the back of the pitching boat. Hold on to each other, they commanded, stay low against the wind and rain.

Some lined up along the ship's rails. Many – like Jessica Hewitt ![]() and Drew Salapatek – were tied together by the climbing harnesses they used to go aloft. One crew member would recall that was Walbridge's idea -- to prevent shipmates from getting separated. Some sailors carried drinking water and emergency locator beacons. Faunt's survival kit included his teddy bear.

and Drew Salapatek – were tied together by the climbing harnesses they used to go aloft. One crew member would recall that was Walbridge's idea -- to prevent shipmates from getting separated. Some sailors carried drinking water and emergency locator beacons. Faunt's survival kit included his teddy bear.

Claudene Christian found herself beside Josh Scornavacchi. True to form, she smiled. Then her smile transformed to a look of determination.

Nearby, Salapatek turned to Hewitt, tethered to him. She was practically asleep from exhaustion. It was clear the ship was about to go down. They were minutes away from inflating and boarding a life raft.

It's going, he told her. Hey kid – we gotta get outta here.

About 80 hours after the decision to set sail toward Sandy, the crew awaited the captain's order to deploy the life rafts and abandon ship.

It didn't come soon enough.

Before dawn, Monday, October 29

Somebody yelled: She's going under!

The 400-ton Bounty rolled nearly all the way over on its right side -- smacked down by a massive wave.

Dazed and exhausted from a grueling fight with Hurricane Sandy, the 15 crew members and their captain were on deck. Some braced themselves. Some jumped into the churning, chilly water.

Others simply fell.

Walbridge hit the water between the ship's rear mast and the navigation shack.

Christian and Sanders, the second mate, were thrown overboard together.

What do I do? What do I do? she asked.

Swirling water from the sinking vessel created a vortex that threatened to suck everything down with the wreck.

Sanders knew they had to swim away.

You have to go for it, he told her.

The last time he saw Christian she was swimming near the ship's rear mast.

Everybody was panicking. Sail rigging and red survival suits bobbed around the boat. The air was filled with shouting and the sound of the howling wind.

Pummeled by hurricane winds and waves, the 52-year-old ship with the Hollywood pedigree sank October 29, 2012, about 100 miles off North Carolina.

U.S. Coast Guard via Getty Images

Then it got worse.

While the crew members struggled to keep their heads above the towering waves, the ship's mast and rigging threatened to beat them to death. The Bounty had turned into a kind of giant fly swatter, slamming down on the sailors again and again.

Prokosh, already suffering with broken ribs and a separated shoulder, got tagged by Bounty's main top yard -- a huge piece of wood that holds the main sail. It pounded him underwater.

One crew member watched helplessly as a rigging spar swung down toward John Svendsen, the first mate. He reached up to block it, but was only partly successful. The rigging dealt his face a glancing blow.

Jessica Hewitt's climbing harness -- tethered to Drew Salapatek -- snagged on debris, dragging her underwater. Salapatek, realizing he was being pulled under too, wriggled out of his harness. Somehow, Hewitt freed herself and returned to the surface.

Not far away, Scornavacchi fought for his life. An emergency kit tied to his survival suit had caught on a piece of rigging. Before he could take a breath, he was pulled underwater.

Thrashing against the tangled debris, Scornavacchi's body ached for air. He was losing muscle control. This is it, he thought. He recalled his promise to his mother and little brother: Don't worry, he'd told them, I won't die on this trip.

Then it happened: The tether connecting the emergency kit to his suit broke loose.

He was free.

Elsewhere, Svendsen ![]() floated alone.

floated alone.

He'd become separated from the crew as the hurricane's winds and waves pushed him farther and farther from the shipwreck. Protected from hypothermia by his Gumby suit, Svendsen carried a beacon that signaled his location.

Several survivors clung to floating debris or linked arms and legs to form human chains. Panic gave way to relative calm as they searched for each other in the darkness.

Eventually a group of seven crew members and another group of six were each able to locate a life raft.

Inflating and climbing inside the rafts was difficult. The Gumby suits were heavy with water, making movement troublesome. The seriously injured Prokosh needed help. An hour passed before all 13 were safely aboard.

For Sprague, it was her first time ever inside a life raft. Deployment and inflating, the crew would later say, wasn't part of their training.

Like Svendsen, Laura Groves carried a locator beacon that could help searchers find her raft. Matt Sanders, on the other raft, also had one.

Deckhand Mark Warner peered out into the darkness. He spied a light atop the other raft – but he couldn't make out anyone inside. Scanning the water, he saw no one.

Overhead, the sound of a circling search plane boosted their confidence: Soon, they would be saved.

February 2013

Fourteen people survived the sinking of the Bounty. Robin Walbridge ![]() and Claudene Christian were not among them.

and Claudene Christian were not among them.

Christian's body was pulled from the sea shortly after her shipmates were rescued. The search for the captain lasted four days. He was never found.

Four months later, Walbridge's and Christian's presence was palpable at Coast Guard hearings in Portsmouth, Virginia. More than once, raw emotions surrounding their deaths raised tensions in the room.

Just hours after deckhand Josh Scornavacchi, second from left, faced what he thought was certain death, rescuers plucked him from the Atlantic.

U.S. Coast Guard

The lead investigator shot an angry look at a lawyer representing Christian's family. As the attorney's questions grew more and more aggressive, Cmdr. Kevin Carroll shouted, "Dial it down!"

Still mourning their daughter's death, Dina and Rex Christian watched the outburst intently from a few feet away. News reporters, nautical bloggers and the maritime authors in the audience shared their surprised reactions by way of silent glances.

The tension followed days of grueling testimony that offered all the power of a TV episode of "JAG," complete with a phalanx of uniformed Coast Guard officers firing questions at witnesses who seemed to choose their words carefully.

The stakes were high. The Bounty's Hollywood pedigree and recognizable name make it arguably the most famous tall ship in the world. Those watching knew the investigation could have huge ramifications on the way attraction vessels like the Bounty are inspected for safety.

Bounty's owner chose to license the ship as an uninspected passenger vessel, a classification described by experts at the hearing as a regulatory no man's land.

The status allowed the Bounty to avoid requirements reserved for higher classified ships -- including a sometimes expensive, time-consuming Coast Guard hull inspection every two years. The ship's classification also allowed it to hire less experienced crew to serve in officer positions.

To charge admission for shipboard tours at dockside, the Bounty required only a simple, brief Coast Guard inspection that checked for obvious safety issues such as major leaks or malfunctioning emergency equipment. The Bounty passed one of these in August, about two months before the disaster.

No safety inspections whatsoever were required for the ship to go to sea.

That's because the Bounty carried no passengers. Under the law, its human cargo – the crew and captain – did not count.

While lives hung in the balance the night of the storm, now careers are at stake. Investigators' conclusions could determine who, if anyone, might lose their license as a result of the disaster. The findings also could be forwarded to prosecutors who would determine whether to file criminal charges.

The Bounty's owner, Robert Hansen, declined to testify. He pleaded the Fifth. Many of the boat's traumatized survivors fought back tears when asked to describe the night the ship went down.

One by one, investigators asked them the same questions: Where on the ship did you last see Claudene Christian? Where was Capt. Walbridge when you saw him last? Were you comfortable with the captain's decision to set sail from Connecticut? Why did Walbridge change his original plan to sail wide to the east of the storm?

The lead investigators, Carroll and the NTSB's Rob Jones, pressed engineer Barksdale and second mate Sanders hard for details about the failed engines, generators and pumps.

They hammered questions at first mate Svendsen about the timeline connecting Bounty's repairs in Maine to the ship's deadly horizontal roll.

Were you satisfied that the ship was seaworthy? When was it clear that the Bounty had lost its battle with the water? Did you suggest to Capt. Walbridge that he reconsider his decision to leave Connecticut? How many times did you and the captain discuss when to give the order to abandon ship?

Astonishingly, nobody pointed fingers.

All 14 surviving crew members testified. Not one leveled any criticism at their shipmates or at Walbridge.

They loved their captain. They trusted his judgment. They sailed into a hurricane. The ship rolled over. A cherished shipmate died and the man they called Captain Robin remains missing.

Federal investigators hammered first mate John Svendsen, left, about the timeline between Bounty’s repairs in Maine and the ship’s deadly roll a few weeks later.

Steve Earley/The Virginian-Pilot

It was almost as if they thought the disaster was unavoidable.

As a sailor might put it: You know, shit happens.

With the conclusion of the testimony, investigators now have the difficult task of weighing the evidence to determine what happened – and the next steps.

Of countless factors involved, which ones contributed to the tragedy most? How much responsibility, if any, rests on the captain?

Was Walbridge a blameless victim of the deadly forces of nature? Did the Bounty sink despite his experience and expert judgment?

Or did he take unacceptable risks? Did he turn his head from serious maintenance issues? Would more training and experience among the crew have averted the disaster or saved lives?

Investigators quoted the YouTube video in which Walbridge boasted about chasing hurricanes. And they heard from Walbridge's former boss, Capt. Richard Bailey of the wooden tall ship Gazela, who said he was astonished that the Bounty sailed toward Sandy. Walbridge, he said, "didn't seem like the type to do something reckless."

Without a doubt, the captain's harshest critic at the hearing was Jan Miles, one of the world's most respected tall-ship pilots and a self-described friend of Walbridge.

Captain of the Pride of Baltimore II, Miles summed up Walbridge's actions in four words: "reckless in the extreme."

He questioned why Walbridge was in such a hurry to get to St. Petersburg that he would sail into one of the worst hurricanes in memory.

For centuries, sailors have told tales about adventure on the high seas. The stories often celebrate a long-missing voyager's return.

This sad seafaring story concludes with the loss of two lives and perhaps the most frustrating of endings: with, as Miles said, "questions that have no answers."

Pinnacle.

The word rolls off Josh Scornavacchi's tongue with a smile -- sounding like the world's greatest healing spa.

A stunningly beautiful mountain peak near the Appalachian Trail in Berks County, Pennsylvania, Pinnacle was among the first places the 25-year-old deckhand wanted to go after the shipwreck.

Bounty's young man with the old soul needed to put 8 miles of spectacular trail under his feet.

The night the Bounty went down transformed Scornavacchi, already a spiritual Christian, into a man even more deeply connected to his faith. That day he was certain he would die. And now he can't always understand how he made it back alive.

For Scornavacchi, answers to the big questions are hiding in the great outdoors.

The breathtaking vistas during his trek to Pinnacle moved him forward physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Mostly, the hike reconfirmed his need to explore.

An undated photo from Bounty during a storm was posted on the ship’s Facebook page. It’s now been entered as evidence in the shipwreck investigation. Bounty’s captain once said he "chased hurricanes."

From Facebook

Around his neck, Scornavacchi wears a symbol of his survival -- a replica piece of ship's rigging -- a small, wooden pulley block.

It reminds him of the Bounty's deadly rigging that he had to overcome that night. It stands for his continued passion for sailing ships and the sea. He also carries with him a 6-inch metal cross that he hopes to send to the parents of his lost shipmate, Claudene Christian.

Although Christian's tall-ship life was among several career reboots, it seemed somehow appropriate that the final phase of her free-spirited life would take place on the ocean, where destinations feel limitless and horizons infinite.

Dina and Rex Christian made sure their daughter's presence loomed large during the Coast Guard hearing. Whatever legacy the Bounty leaves for the future of the tall ship community, the Christians likely will be a part of it. In the coming weeks, their attorneys plan to file a lawsuit over their daughter's death, probably in a New York City federal court. Her parents chose to follow their attorney's advice, declining requests for interviews.

When Walbridge's widow, Claudia McCann, thinks about the Bounty's memorial service last December in Fall River, Massachusetts, she remembers the faces of supporters who surrounded her with love. Some were Bounty survivors -- the same faces Walbridge scanned that day in New London when the captain made his decision to sail.

The service, held aboard a retired Navy battleship, drew hundreds of mourners whose lives had been touched by Walbridge. McCann could feel their positive energy. And it helped her begin to heal, just five weeks after she'd lost her husband.

The eulogist praised Walbridge as a "fine, solid mariner … who was loyal to his ship and loved her till the end."

Tears flowed. A ship's bell rang. A wreath was tossed into Mount Hope Bay.

Four months later, the pain of her loss has eased. But McCann knows she still has a ways to go. And she realizes troubled waters lie ahead.

Eventually, McCann will have to face the conclusions of the Bounty investigation. Whatever judgment the Coast Guard renders, McCann said it's going to be a very trying time.

In the tall ship community, dinner conversations surrounding the Bounty have become so volatile, the subject has been unofficially banned aboard some vessels.

Some say the captain's decision to leave Connecticut put the crew's lives in danger. But the Bounty's shipmates came together to save themselves. And they continue to look after each other.

"They're my family," said the Bounty electrician, Doug Faunt. "Closer than my family."

Earlier this month, Faunt and five of his shipmates reunited to sail once again.

This time, a 14-foot Sunfish had to do.

The reunion was hosted by deckhand Anna Sprague in the quaint Georgia beach town of Tybee Island, just outside Savannah, where Sprague first fell in love with the Bounty.

Scornavacchi was there, as were ship's cook Jessica Black ![]() and deckhands Mark Warner and Jessica Hewitt. They took turns in the tiny boat, enjoying nice sailing weather: temperatures in the 70s, mostly sunny, winds around 10 mph. It was a great chance to catch up, hang out and let off steam after the stressful hearings.

and deckhands Mark Warner and Jessica Hewitt. They took turns in the tiny boat, enjoying nice sailing weather: temperatures in the 70s, mostly sunny, winds around 10 mph. It was a great chance to catch up, hang out and let off steam after the stressful hearings.

The survivors call and chat briefly almost every day, says Hewitt. They've become so tight they named themselves The Crew.

While surfing recently in San Diego, Hewitt took a spill, triggering a sort of flashback – a scary reminder of her ordeal.

The disaster changed Bounty’s survivors and their relationship with the seafaring life they loved so well. It shifted their perspectives on danger, caution and risk – in surprising ways.

Maurizio Gambarini/DPA/Landov

Sprague, Bounty's youngest crew member and still a student, acknowledged the disaster has changed her. "I'm not quite as carefree," she said. "I'm more cautious."

But not too cautious.

Her parents told her they hoped the tragedy wouldn't end her love of sailing -- and it hasn't. "I'm not going to spend my life avoiding death," she said. "I'm going to spend my life living it."

For her, and many of the others, that means a life at sea.

Some survivors have been talking about teaming up to buy a new vessel. "We already have a crew," Faunt said with a smile. "We just need a boat."

Scornavacchi is searching for sailing jobs for himself and his girlfriend, who's been bitten by the tall ship bug -- just like Claudene Christian a year ago.

Hewitt has already become the first Bounty member to return to the tall ship life. She's aboard the wooden schooner Amistad, a replica of the infamous 19th century slave trading ship based in Mystic, Connecticut.

For all the mystery and uncertainty that still surrounds the Bounty, this much is clear: Crew members lost their captain, but not his passion.

As long as tall ships sail, adventurers will accept the risks to answer the call of the sea.

CNN's Thom Patterson based this story on more than 40 hours of testimony from Bounty survivors and other witnesses at hearings held by the U.S. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board investigation in February in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Quotes from testimony are used only when witnesses recalled hearing or saying those exact words.

Patterson gathered additional information from independent interviews with the Bounty's survivors, witnesses who helped to repair the boat and former crew members who served on the vessel during previous tours. Some details surrounding Bounty inspections and the rescue came from the U.S. Coast Guard.

The Bounty's owner, who declined to testify at the hearings, also chose not to respond to allegations from witnesses and from former crew members contacted by CNN.

For information about tall ship operations, legal regulations and federal inspections, Patterson consulted with U.S. Navy veteran Mario Vittone, a former U.S. Coast Guard vessel inspector and rescue swimmer.

Location data for the Bounty was gathered from sailwx.info, a ship tracking website.

Some weather data, including location, conditions and forecasts for Hurricane Sandy, came from the National Weather Service.

Additional credits: Curt Merrill, Aimee Schier, Kate King, Elizabeth I. Johnson