Hotel Death

It's a place of celebration, where dying guests are promised freedom for their souls. And where one man, whose father is No. 14,544 in the ledger, finds himself torn between two worlds.

By Moni Basu, CNN

Photographs by Atul Loke/Panos Pictures for CNN

Varanasi, India

A 10-hour journey on Indian roads can be difficult and this one, fueled by faith, was more so.

Dinesh Chandra Mishra packed moth-eaten woolen blankets for the trip along with muslin and cotton quilts that had once been crisp and white. He also brought a single-burner kerosene stove, kitchen utensils and a rough estimation of clothes -- though he could not possibly calculate how long he would be away from home.

He spent one-fourth of his monthly schoolteacher's pension to hire the car that carried him and his belongings as well as his mother, sister and ailing father from their village of Gopalganj to Varanasi.

From the start, he was conflicted about the trip. It was not emotionally easy to bring his father to this city with only one purpose: to die.

Many years ago, Mishra's grandfather had spent his final days at a "liberation house" for dying pilgrims in Varanasi. Now the destination was the same -- Kashi Labh Mukti Bhavan, one of two remaining homes for those who arrive here at the eleventh hour, when death is imminent.

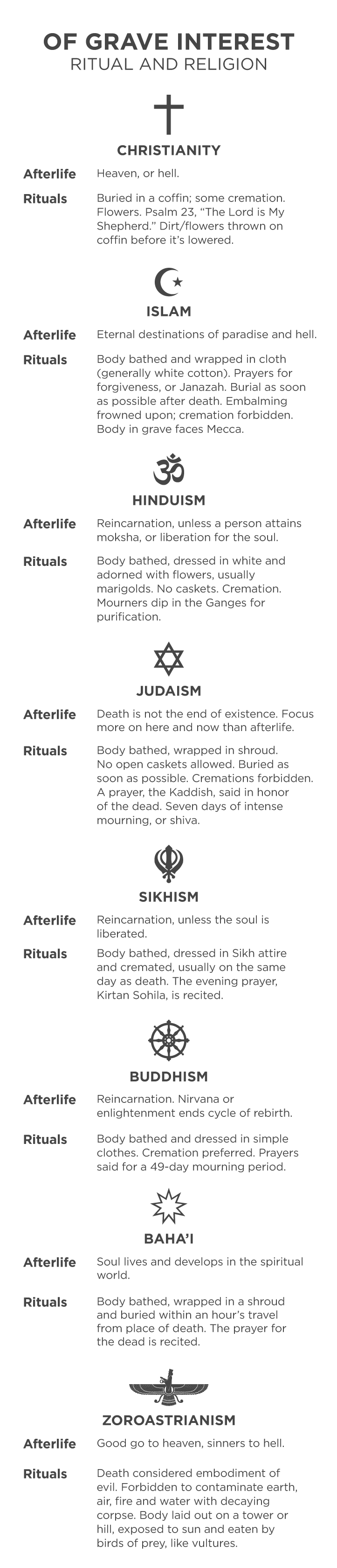

To take God's name and die in Varanasi is to attain moksha, a term that can be interpreted in many ways but is generally understood by Hindus to mean freedom for the soul, a release from the constant cycle of rebirth.

Hindus believe a person builds up karma or a culmination of deeds during their lifetime. Karma can be good or bad, and it affects future lives for Hindus. The sect of Hinduism to which Mishra belongs believes that dying a good death in Varanasi forgives bad karma. Even a murderer can achieve moksha here.

Mishra, 63, had also accompanied his grandmother to Mukti Bhavan and stayed a month and a half. She grew restless and begged him to take her home. So he did. She died three days later. Mishra lived with the guilt of denying her salvation.

Tourists flock to Varanasi to experience its intense spirituality. Many tour the Ganges River to witness the activities along the city's ghats, the wide steps that lead to the water.

Now it was his father's desire -- as well as his entire clan's -- that the 83-year-old take his last breath in Varanasi, known in ancient times as Kashi, the most sacred place for devout Hindus. If he failed his father, as he had his grandmother, Mishra could not live with himself.

Salvation was the hope that kept Mishra going in his arduous journey. It was a hope he'd held all his spartan and sometimes inhospitable life but one that he felt more fervent now than ever. Still, it was not an easy decision to travel to Varanasi.

He'd left at home his wife, his only daughter and a situation of utmost urgency, one that required his attention. If he did not return home soon, he might mar forever the course of his daughter's life.

Mishra arrived in Varanasi balancing life and death.

I had never been to the homes for the dying here. But having grown up in a Hindu household, I understood the lure of Varanasi, believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited place on the planet, as ancient as Babylon.

The city is intense and in-your-face spiritual. Hindu holy men with vermilion and saffron smeared on their foreheads wander labyrinthine lanes. Oil lamps, called diyas, burn day and night, and the sounds of brass bells and mantras, or incantations, reverberate far past the grounds of Varanasi's 3,600 temples.

Believers and tourists alike, from the world over, want to touch the soil here and bathe in the sacred waters of the Ganga, as the Ganges River is known in Hindi, in an act of purification.

Varanasi has always been known as the city of light. But a more appropriate moniker might be the city of death.

The end of life here is stark and out in the open, for all to see. Bodies blanketed by white shrouds and orange marigolds are brought to the ghats, the broad steps leading down to the Ganga. Funeral pyres, especially at Manikarnika Ghat, the most sacred of cremation places, burn nonstop, melting human flesh on piles of mango wood. Sometimes, parts of bodies remain after the flames go out; stray dogs surround the smoldering embers. Those smells and sights reminded me of my time covering the war in Iraq.

Many of the city's residents make a living from death. They include the Doms, the untouchable caste of Hindus who work at the cremation sites as well as the astrologers and priests who gather at the river. Part of the fascination for visitors, especially foreigners, is to bear witness to the process of dying.

The man who acted as my guide through Varanasi's assault on the senses knows his hometown better than most. I found Nandan Upadhyay through a blog he writes called "Groovy Ganges." He understands the magnetic draw, the cosmic energy swirling about the city. But he is always keenly aware of Varanasi's 21st-century woes of poverty, pollution and overpopulation. I felt certain I was in good hands though I had no way of knowing how death would reshape our acquaintance.

Upadhyay hails from a traditional Hindu family from the high caste of priests. I considered myself just a step beyond "Hinduism for Dummies"; I saw Upadhyay on textbook level.

For seven years, he has devoted himself to building a business that takes foreigners on walking tours of his hometown. And out of entrepreneurial necessity, he perfected his spiel on the Hindu rituals of death.

He knows the numbers that draw gasps: 32,000 bodies are burned at Manikarnika Ghat every year. And he recites all the rules of death that are specified in ancient texts. But he told me he remains highly skeptical.

He didn't care to have a priest chant prayers in Sanskrit while he bathed in the Ganges, in waters sullied in recent years by industrial waste, sewage and slaughterhouses. "How can this water be pure?" he asked. He took pride in joining other Indians who defiantly pledged not to bathe in the holy river again until the government did something to clean it up.

Not long before I met Upadhyay, one of his close friends lost his father. Upadhyay went to the funeral and hugged the grieving man, despite warnings that touching anyone at a cremation ground is to become impure yourself. Others who touched Upadhyay that day had to bathe and change clothes before entering their homes.

Upadhyay thought it silly that these things mattered more than comforting a dear friend. Not that he wasn't spiritual. He was. He just didn't believe in blind devotion to practices that seemed misguided to him.

Girish Mishra's daughter attends to her dying father at Mukti Bhavan.

A holy man meditates on the banks of the Ganges or the Ganga, as it is known in Hindi. Hindus believe the river's waters are sacred.

Motorbikes, bicycles, pedestrians and cows compete for space on the streets of Varanasi.

That's why he could not understand Hindus who believed in Varanasi's powers of salvation. He confessed he would never take the trouble to bring his own father to Mukti Bhavan to die. The practice seemed so morbid.

I understood his reaction. I'd been raised in an extended family that embraced Hinduism, though my father shunned religious practices in general. He even made me promise that no rituals would be performed after his death.

What mattered in life, my father said, was karma. Be a good person, he told me. The conversation always stopped there, with the ending of life. There was no discussion of what the consequences might be after death.

That would change for me in Varanasi as Upadhyay and I made our way to a home for the dying. Over a few days at Mukti Bhavan, we both began to see death in a new light. We were surrounded by people who spoke of dying with nonchalance. We spent our waking hours in a place that lacked warmth and expressions of love or any of the other emotions we linked to the process of dying.

And yet, in that environment, death would suddenly become more intimate than either of us could have predicted.

Everyone in Varanasi seems to know where Mukti Bhavan is located, though there are no signs leading to it from Church Godowlia, the city's busiest intersection, where a torrent of motorcycles, cars and cycle rickshaws stop for nothing and no one. Crossing the streets, I visualized my own death on occasion.

I expected Mukti Bhavan to be a clean, bright hygienic place, like a hospice in America. It wasn't.

It sits on a narrow lane, next to a couple of shabby shops selling speakers and other audio equipment. The early 20th-century brick and plaster building must have belonged to a wealthy Varanasi family at one time. I tried to envision its past grandeur with marble floors in the outer rooms, high ceilings and an interior courtyard.

Today, its appearance is suitably sober and dark for a place of death. Only at the height of day does sunlight stream in through cracks in the shutters and illuminate the millions of microscopic dust particles in the air. At night, dim fluorescent bulbs provide a modicum of light -- that is, when there is electricity from the city.

The house has 12 rooms, but the manager, 60-year-old Bhairavnath Shukla, has been known to set up beds for people in the corridors and courtyard. He has worked here for 43 years and rarely turns away a person who he believes is in need.

Shukla pondered a career in the army and tried his hand as an educator before he felt a calling to do God's work in Varanasi. He's spent a lifetime studying Hindu texts, and if you question him about salvation, be prepared to sit for a while. It's like asking a preacher about the Ten Commandments and the answer is the entire book of Exodus.

Shukla's guidance on whether a person is near death comes, he says gesturing, uparse, meaning from above. He sternly lets people know he is not running a charity for sick people (though Mukti Bhavan is funded by a charitable trust set up by one of India's wealthy industrialist families). This isn't a place where people can park themselves just because they have nowhere else to go.

People travel here from near and far to die. Shukla claims he has even had guests from England and Mauritius. But most are devotees of a sect of Hinduism from neighboring states who believe in the powers of this city. They arrive in Varanasi and either lack money or are rejected by established hotels and guesthouses that quickly realize their guests will check in but not live to settle the bill.

Manager Bhairavnath Shukla says there is nothing ghoulish about the home he runs. People are not dying, he says. They're gaining moksha, or salvation.

Shukla uses the front room in the house as office space, though he is rarely there by day. He is busy running a staff of priests, who live on the premises. He fingers his prayer beads all day long as he makes sure the priests tend to the small temple inside the house and the evening kirtan, a chanting of hymns accompanied by drums, bells and harmonium.

Near the doorway is a sign in Hindi listing house rules. The first says only people who believe in the idea of salvation in Kashi are allowed to stay here. Among the other rules: Only Hindus are allowed. People with contagious diseases will not be admitted. If you are caught having sex or engaging in "other sinful activities," you will be asked to leave. Lodgings are free, but guests will be charged for electricity. Only 15 days of stay are permitted. After that, the manager will make a decision.

At night, Shukla sleeps on a small cot in the office -- in case anyone shows up after dark. On the top shelf of a built-in bookcase he keeps piles of dust-laden scriptures, Ganga jal, or Ganges water, in plastic jugs and a ledger of everyone who has checked in.

It is a ghoulish list of all who perished here, something that might keep many awake at night. But not Shukla.

"If people were dying here," he laughs, "this would be a haunted house, a house filled with ghosts. But they are not dying. They are gaining moksha."

In the ledger, Mishra's father, Girish, is No. 14,544. He has already been at Mukti Bhavan for nearly three weeks when I arrive. Shukla tells me he decided that Mishra's father could remain beyond his 15 days. He felt certain death was at hand.

Funeral pyres, especially at Manikarnika Ghat, the most sacred of cremation places, burn nonstop, melting human flesh on piles of mango wood. About 32,000 bodies are cremated here every year.

Japanese tourists stop at Mukti Bhavan to learn how Hinduism explores the end of life in a frank way.

Dinesh Mishra prays at the temple at Mukti Bhavan for guidance from God on how to face his dilemma. He felt torn between staying with his father and returning to the daughter he left behind at home.

Upadhyay and I watch Mishra emerge every morning from Room No. 6 at the back of the house. The windows are tightly shut. Girish Mishra cannot stand the cold or any sunlight in his eyes. He lies motionless on a hard, wooden cot and rises only once a day to sip milk and swallow a few morsels of flatbread and vegetables.

Mishra positions himself in the front yard on a wobbly bench under the sun, trying desperately to shed the early chill of the day. It is February, and Varanasi still feels quite cold at night, though summer's sizzle seems imminent at the height of the afternoon.

Before he retired, Mishra taught English for 30 years at schools at home in Bihar. He credits his position in life to his father's hard work and support.

He likes to quote writers such as Alfred Tennyson and holds on to their lines as salves for stress. "Cleave ever to the sunnier side of doubt. And cling to faith beyond the forms of faith."

He leans over and tells me: "I believe in faith. I believe in destiny. What is lotted cannot be blotted."

He speaks surrounded by the buzz of routine activity, some of it so mundane that it is perplexing for a house of death -- at least it seems that way to outsiders like me.

The priests undertake a lavish four-hour ritual every morning to undress the deities in the temple -- Ram, Krishna and Hanuman, the monkey god -- and bathe them in milk and water. They wash the brass offering plates and glasses and return everything to its rightful place. These acts are a way to express their devotion to God.

Shukla grabs a steel bucket, pours a drop or two of Ganga jal in it and takes his turn at a tube well to bathe. All those who work and live at Mukti Bhavan take morning baths out here in the open. That includes two teenage brothers, who have lived on the compound for the last decade, surrounded by death. They say their mother was frightened at first to live at the compound.

But then everyone got used to the sickly bodies, the soiled sheets. The screams of pain became background noise, like the constant horns of motorcycles and rickshaws we can hear outside the gate.

Late in the morning, the children of the Mukti Bhavan staffers head off to various schools in their uniforms. The priests keep busy fussing over a small garden and chasing wild monkeys off the trees and perimeter walls. From the outside, no one would know there are rooms here reserved for death.

The depth of Mishra's predicament also is not apparent at first, but Upadhyay and I can see that even amid the constant happenings at Mukti Bhavan, he lives in his own world, lost in waiting for his father to die.

He consults the three priests on the premises. He saunters over to the wrought-iron gate, painted forest green and always kept chained and locked, though loosely enough to allow people to enter and exit.

He buys cauliflower and potatoes from the market for his sister to cook in their room. There's no cafeteria or food services at Mukti Bhavan. Mishra knows the drill from his previous visit here with his grandmother; the families of the dying have to fend for themselves.

He ventures out to see astrologers on the ghats and prays at one of the nearby temples.

Even residents get lost in the labyrinthine lanes of Varanasi, believed to be as ancient as Babylon.

Shukla tries to calm Mishra.

"Don't worry," he tells him. "Your father will die soon."

"What a strange thing to say," I tell Upadhyay. It's the very opposite of what he and I or anyone else I know would tell a person who is watching a loved one wither away.

But death is not to be mourned here, we learn. It is not even a word that is uttered much. More often, Shukla refers to death as mukti, or liberation. He and everyone else at Mukti Bhavan see death in Varanasi as a marriage of one's soul with God.

And just like a wedding, it is an occasion for joy.

Joy is not a part of Mishra's life at this moment. "I am facing a dilemma," he announces.

The white stubble blanketing his face -- he hasn't shaved in days -- looks like unevenly sprinkled confectioner's sugar. He adjusts his glasses, though he's oblivious to the film of fingerprints and dust, and begins to divulge why he is so troubled about his trip to Varanasi.

In custom with his culture, he feels obligated to get his daughter married. When he left his village for Varanasi, he abandoned crucial negotiations with the family of a young man he thought suitable. The deal, he feels, could easily fall through because of his absence.

He will always blame himself if, in the end, he fails to negotiate a new life for Bandana. As her father, he is responsible. But he also could not live with himself if his father missed out on dying within the boundaries of this hallowed city.

Mishra scans the political headlines of the day in a Hindi-language newspaper, occasionally glancing over at his sister, who is fastidiously hanging her freshly rinsed nylon saris to dry on a crowded clothesline.

"We will wait for a few days and then decide what to do," he says, explaining how enormous a task it is to arrange a wedding.

Mishra wishes there was someone back home who could help him settle things for his daughter. He has little money, he says, and there are many people who owe him. They should step forward now to settle up their loans, he thinks, so he can send word to the prospective groom's family that he has enough for a dowry.

A groom makes his way to his wedding through the narrow streets of Varanasi.

Children of employees lead normal lives at Mukti Bhavan even though they are surrounded by death.

Mannequins sport women's fashions at a street-front store in the heart of the city.

Dowries were designed to transfer familial wealth to a daughter at the time of her marriage, but they essentially became forms of payment for a man to agree to marry a woman. The custom is outlawed but still prevails in many parts of the country.

Mishra made sure all three of his children finished school; many kids growing up in rural India don't. He is proud his sons have good jobs now. It's his daughter's turn to stand on her own. The first step toward that for a woman in Mishra's society is marriage.

The groom has to be handsome. He has to hold down a stable job, preferably working for the government. And he should not be an alcoholic. Too many men in his village, he says, drink heavily and then abuse their wives.

Family members have been to see a suitable boy. "That's why it is urgent I return home," he says.

I can hear the distress in his voice.

"He is in a difficult position," Upadhyay agrees.

Shukla, the manager, has been listening intently to our conversation. He shrugs off Mishra's problems and advises him to stay in Varanasi.

"You should give priority to your father," he says. "He gave you birth. He has limited time left. There will be lots of time for other things."

Upadhyay understands Shukla's advice. He, too, feels enormously indebted to his father.

Upadhyay eloped with his wife when he was in the 12th grade. She was pregnant and gave birth to their son before they could marry. It was scandalous in India and even more so in Varanasi's conservative circles. Some of Upadhyay's relatives and friends shunned him.

"My life was controversial, but my father stood by me," he says.

He helped Upadhyay get back on his feet. At 71, his father is considered older than someone that age might be in America, but at least he is in good health, his mind still sharp.

Upadhyay is thankful he still has plenty of time to think about his father's mortality, to sort out his beliefs on salvation for the soul.

For many days, the Mishras have been the only guests at Mukti Bhavan. But on this afternoon, Shukla gets word of another potential guest.

On the phone is a relative of an elderly woman who has been admitted to the Banaras Hindu University Hospital a short distance away. The family wants to bring her to Mukti Bhavan; doctors have informed them there is little left to be done.

The hospital is in Varanasi but outside the boundaries of ancient Kashi.

"You can go to heaven if you die there," Shukla explains, citing Hindu texts that define a four-kilometer (about a 2.5-mile) zone outside Kashi as special. "But you will be reborn."

That's why many people choose to take the very sick out of the hospital and bring them here, he says.

He's already turned away two families today. The patients did not seem on the verge of death to Shukla. He will wait to see the condition of the hospital patient before he says yes and adds her to his ledger.

While he waits, a steady stream of other people go in and out of the gate. Some wander in just to sit in the front yard, somewhat of an oasis in a city of hustle and bustle. Others have a more specific purpose.

A young, barefooted woman covers her head with her black scarf, or dupatta, and offers a prayer with Ganga jal in front of a banana tree, considered a symbol of the god Vishnu, the preserver and protector of the universe. Two Muslim men ask for alms for a pilgrimage. "In the name of Allah," they say to Shukla and the Hindu priests.

Shukla takes out a 10-rupee note and slips it into the hands of one of the men. After they leave, he grumbles about how people will use any excuse to make a fast buck. "Emotional blackmail," he says.

Just because this is a hospice, people think they can come in and ask for anything, he says. "Can you imagine? Even Muslims come to beg here."

As the hours tick by, the expected guest from the hospital does not arrive. "Maybe," Shukla says, "she has already left us."

Then, as the afternoon continues its lazy crawl -- waiting for death can become tedious -- a white Mahindra SUV arrives at the gate.

At least seven men pour out of the car. In the back seat is a 105-year-old woman. Her relatives tell Shukla they drove her here from their village and that she has not eaten solid food in a month. By comparison, Mishra's father looks good. Shukla inspects her and concludes she has at most three days to live.

A priest shows her family to Room No. 5, next door to the Mishras. They inspect the barren room with whitewashed walls and two cots. And accept.

Mua Kuvar Tiwari is guest No. 14,545.

A Hindu holy man, adorned in marigolds, prays on the Ganges. Behind him, men launder sheets and clothes, one of many activities that take place on the river every day.

She has never married. She has no children. Her nephews decided to bring her here from across the state border in Bihar when she stopped opening her eyes and they sensed the end was near.

"Her work on Earth is over," says her grandnephew Arun Kumar Tiwari.

The Tiwaris quickly unpack the bedding they have brought and place the dying woman on a cot. They ask me to use the compass on my iPhone to make sure her feet are pointing north, in accordance with Vastu, or Indian feng shui.

Her nephew Jaishankar Prasad Tiwari says his aunt was on medication for congestion and joint pain but she has survived solely on water the last 15 days.

"It is very important to me that she dies here," he says. "It means I have paid off my debt to her."

He notices the sullen look on my face, my head bowed. "This is not a place for sadness for us," he says, as though to comfort me.

"You don't come here to get better. You come here to die. Even she feels happiness," he says, pointing to his aunt.

I can see her in the dim light. Her legs are stiff and thinner than my arms. She is gasping for air.

Mishra pokes his head into his new neighbor's room. Now there is another rogimarnewala, a sick person who is about to die, in the house. It comforts him to know there are other people here who understand.

The Tiwari family lights sandalwood incense by the ailing woman's bed and keeps vigil sitting on the floor. Every hour, they force open her mouth and give her a few drops of Ganga jal. It is like the blood of Shiva -- the god of destruction and purification -- entering her body.

A priest comes by to chant prayers. He waves an earthen lamp filled with camphor, commonly used in Hindu worship ceremonies. The room fills with white smoke so thick that Upadhyay and I almost can't see the group of a dozen Japanese tourists who have made their way into the courtyard.

They are on a Buddhist pilgrimage in India and have stopped here after hearing about Mukti Bhavan. They barge into the Tiwari family's room, stare at the dying woman. Then they shuffle next door to Mishra's room. Some even click their cameras.

Mishra's sister is cleaning up after lunch. She dumps whatever biodegradable waste there is in a small plastic bucket in the courtyard. (Shukla insists it be fed to the cows outside.) She sizes up the strangers who are so intrigued by her father's condition. She has never seen Japanese people before.

Upadhyay and I find the visit jarring. It's almost as though death were on display at a museum. How is this not voyeurism? I ask.

One of the tourists, Takeo Fukikura, has brought his 8-year-old son with him and tells me I am off with my line of questioning.

"This is very heavy," he tells me. "We are digesting it all."

He says they mean well. They are interested in learning about how Hinduism explores the end of life in a frank way, how Hindus do not shy away from death. Nowhere has that been more apparent to them than here at Mukti Bhavan.

After the Japanese tourists leave, Shukla tells me he does not mind such interruptions. In fact, usually he gives visitors permission to explore Mukti Bhavan. His goal is to enlighten them.

"The people who visit here get a very different insight into death," he says. "There are no injections, no medicine. Nothing from the modern world. This is death in its purest."

With each passing day, Mishra seems more agitated, more distraught about his presence at Mukti Bhavan.

On Sunday, he is unable to do anything he has planned, not even take a walk down to the river to feed the fish, considered an auspicious act for Hindus. The only thing he can think of is his daughter's wedding.

Mishra tells Shukla he plans to take a train back to his village, Gopalganj, perhaps as soon as the next night. Shukla does not approve and reminds him he will regret leaving his father's side.

Relatives of 105-year-old Mua Kuvar Tiwari prepare her body for cremation.

Munilal Tiwari, the eldest male relative of his aunt, performs last rites for her at Manikarnika Ghat before the funeral pyre is lit.

Varanasi's cremation ghats can be fascinating -- and shocking -- to foreign visitors who are not used to seeing death out in the open, in its purest.

"It is a choice between starting a life and death," Mishra says. "I cannot fail my daughter."

He busies himself buying the supplies his sister and mother will need in his absence. Cough syrup for his father, vegetables, flour, rice. He adds money to a prepaid calling card for his mobile phone. He goes in and out of the gate. Sometimes he has a purpose and when he returns, it's with something in his hands. Other times, he wanders the congested streets of Church Godowlia; the chaos of the city brings a strange sort of relief.

He calls a relative, a cousin who is younger, and asks him to check on his family every day. What will happen if there is an emergency? What will happen if his father dies?

It is in the midst of all this that Upadhyay's Samsung Galaxy phone lights up. It's his wife.

"Your father is ill," she tells him, her nervousness apparent to him by the quiver in her voice. "I am not sure what's wrong. Please come home."

Not even a half-hour goes by before I learn that Upadhyay's father suffered a massive heart attack and died.

His is not a death anyone expected. No one was prepared. No one was keeping vigil. Upadhyay's biggest regret is that he did not make it home to see his father one last time.

At Mukti Bhavan, I break the news to Shukla.

"Moksha hua. Moksha hua," he declares. Upadhyay's father has attained moksha.

"Nandan should not cry," he continues, describing life as being like a movie that plays out and when "The End" flashes, a new movie begins with a new set of actors.

What matters, he says, is one's relationship with God, not with other people.

At this moment, I am not listening to Shukla's philosophy anymore. I know how devastated Upadhyay must be to lose his father. Upadhyay is 31 and has never lived away from his parents. It is not unusual in India for sons to continue to live at home even after they are married.

These thoughts consume me the next morning at Harishchandra Ghat, the smaller of the two Varanasi cremation sites on the Ganges. I am not here for Mishra and his father, as I had expected to be, but for Upadhyay and his two brothers as they perform last rites for their father.

There is little grief on display. Upadhyay's younger brother is the only one in tears.

They lift their father's body -- Hindus do not use coffins -- onto a pyre of mango logs, the kind of wood prescribed for funerals in Hindu texts. A priest chants from Hindu scriptures and anoints the body with clarified butter. Upadhyay's older brother has shaved his head and wears white muslin garments. He carries a torch and walks around his father's body three times. Each time, he touches the fire to his father's mouth.

I watch intently from the top steps of the ghat. There are no other women around. Funerals are a man's task in Hinduism, and it is always the eldest son or grandson or closest male relative who lights the pyre.

When my father died, my brother was not in India, and the funeral responsibilities fell on me. I kept my promise to my father about not performing the rituals he despised, though I had no choice but to take his body to a crematorium near the Kalighat Kali temple in my hometown, Kolkata. But that facility operated through electric furnaces; it looked and smelled nothing like the funeral pyres in Varanasi.

I stood by my father's body, limp on a bamboo bier on the ground, and waited for hours before his turn came. Two of my closest friends were with me when crematorium workers slid the body into a furnace. Uncovered. Unhindered. Undignified, I thought.

I collected some of his ashes and bone fragments and sprinkled them into a canal that flowed from a tributary of the Ganges. I watched the dusty remains of my father disappear into the dark, dense water. Two months later, my mother was cremated the same way.

I'd thought about losing my parents throughout the week as I listened to Shukla talk about dying. Human relationships, he told me, mean little at the end of one's life. Part of gaining moksha and joining God, he said, is to let go of all earthly desires, including the attachments we have to loved ones.

The concept is difficult for me to grasp, and even more so as I watch Upadhyay and his brothers. The oldest lights a fire inside his father's mouth for the last time, then the workers on the ghat set the entire pyre alight. It can take four or more hours for the flames to consume the body of an adult man.

I'd never thought much about rebirth or the possibility of moksha when my own father died. But I do now.

Upadhyay is still dressed in the striped button-down shirt, sweater vest and Levis he was wearing the day before. But he is barefoot, the silt and scum of the river staining his feet and jeans. I wonder if he will take a dip in the Ganga, as is required to cleanse oneself after a cremation.

This is what Mishra had hoped to do in Varanasi. He had gone to great lengths to ensure a funeral for his father on sacred ground. Instead, the man before me now did not expect to perform these acts anytime soon.

Death rituals helped Upadhyay make a living; they were not something he believed in. But things that had seemed like silly formalities suddenly took on new import.

At Mukti Bhavan, time is standing still for Mishra, who might have given anything to be in Upadhyay's place. Mishra's father is no worse than he was when he arrived in Varanasi. And Mishra's daughter is no closer to a wedding.

I'd watched him sit down with the priests every evening for hymns and prayers. But on the night after Upadhyay's father died, Mishra is busy packing his clothes in a small black duffle bag for the trip home. The rusted zipper isn't budging, and a friend uses candle wax to pry it loose. Mishra gives a last set of instructions to his sister.

"Don't skimp on what he needs. Give him grapes. Give him milk. Make sure he drinks a half-kilogram of milk every day."

Milk is the one thing that Mishra has not been able to buy in advance because there is no refrigeration at Mukti Bhavan. He tells his sister that Shukla's staff has offered to go to the store every day.

"Do we have enough money for that?" she asks.

Mishra hands his sister a bundle of seven 100-rupee bills (about $11).

"If Babaji (father) asks to eat anything, buy it," he says.

He had wanted his Babaji to die at Mukti Bhavan, but he cannot bear the thought of not seeing him again, of not being there at his funeral. Hindus are not taken to morgues; their bodies are not preserved. They are cremated hours after death.

Mishra rolls down the dingy quilt to uncover his father's face.

"I'm going now, Babaji. I'm going back to the village," he explains. "Please understand. I have to go back for Bandana."

Mishra wipes tears from his eyes and flings his bag over his right shoulder. He slips through the front gate and disappears into the crowd outside, hoping to find his own salvation.

I've had years to think about the ending of life since my father's death in 2001. I don't know if there is such a thing as moksha, but I feel my father's presence every day. My time at Mukti Bhavan and in Varanasi solidified my inclination to believe we all have souls.

Mua Kuvar Tiwari, the 105-year-old woman who checked into the room next to Mishra's father, died a few hours after Mishra left for the train station to return home to his village in the state of Bihar. The men in her family cremated her at Manikarnika Ghat. They believe she attained moksha.

Dinesh Mishra returned to Mukti Bhavan a week later and was with his father, Girish, when he died on February 16. Mishra cremated him at Manikarnika Ghat and said his hopes were fulfilled. He is still searching for a groom for his daughter and does not yet have enough money for a dowry. "This year is not in my hand," he says. "It's in God's hand."

Death in Varanasi brings moksha, Hindus believe, and a release from the constant cycle of rebirth.

Nandan Upadhyay shaved his head on the 10th day of mourning. He refrained from commercial toothpaste and used one made from leaves of the Neem tree, believed to have healing qualities.

He bathed in the Ganges amid the waste and the ashes of the dead. He bowed his head in prayer and found comfort in the priest's prayers in Sanskrit, even though he did not understand everything that was said.

When he finally returned to working as a tour guide, he could no longer talk in detail about death and cremation.

He said the time he spent with me at Mukti Bhavan helped him cope with his father's sudden death. He took solace in Shukla's words about celebrating the marriage of one's soul with God. He even thought about asking Shukla to visit his mother in her time of grief.

"Who knows what is the truth?" he asked in a recent phone conversation. "I know very well these are very regional ideas. It is different here in Varanasi than it is in Europe or America.

"But at the same time, it was my father," he said. "So why should I make that mistake?"

In a critical moment, the question marks faded for Upadhyay. He wanted to do everything possible for the soul of his father. Just in case.

Follow CNN's Moni Basu on Twitter.

CNN LONGFORM

The Uncounted

One tragic number is known: 22 veterans kill themselves every day. But another is not: How many military spouses, siblings and parents are killing themselves? What is war's true toll?

'My son is mentally ill'

He is 14 and hears voices. He's been hospitalized more than 20 times. Stephanie Escamilla is tired of seeing the country focus on the mentally ill only when there's a national tragedy. So she and her son are telling their story.

24 hours in the world's busiest airport

With 95.5 million passengers and 930,000 takeoffs and landings, Atlanta's airport is No. 1. CNN pulls back the curtain to expose a world unto itself -- and countless untold stories.

The girl whose rape changed a country

Her landmark case awakened India four decades ago. But did she manage to love, have children, find happiness? New headlines about rape in her homeland send CNN's Moni Basu on a journey to find out.