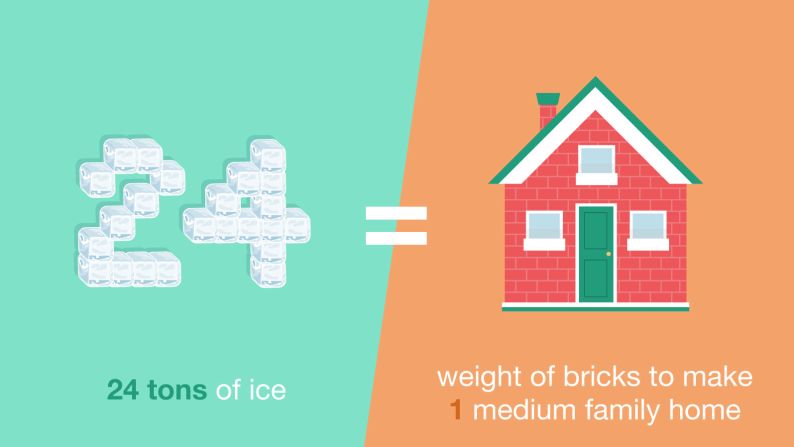

Water scarcity in the UAE is second only to Kuwait in the Middle East, so when it comes to farming, a smart approach is required. Now high-tech, low-water agriculture is set for a new superlative with the announcement of the world’s largest vertical farm in Dubai – and the produce could soon be coming to a flight near you.

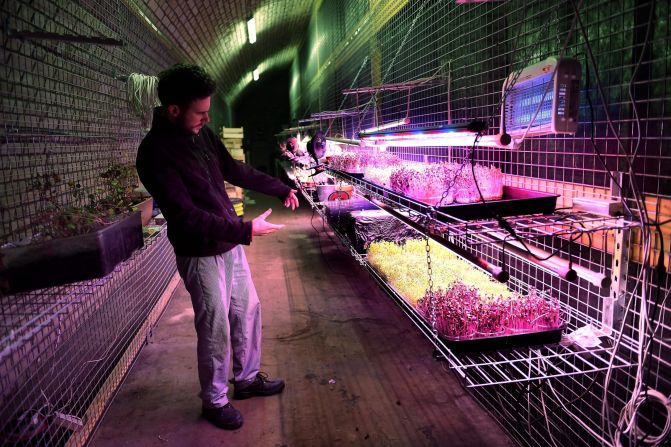

The 130,000-square foot, $40 million facility will begin construction in November, and is a joint venture between agri-tech firm Crop One Holdings and Emirates Flight Catering, suppliers of approximately 225,000 meals every day from its base at Dubai International Airport.

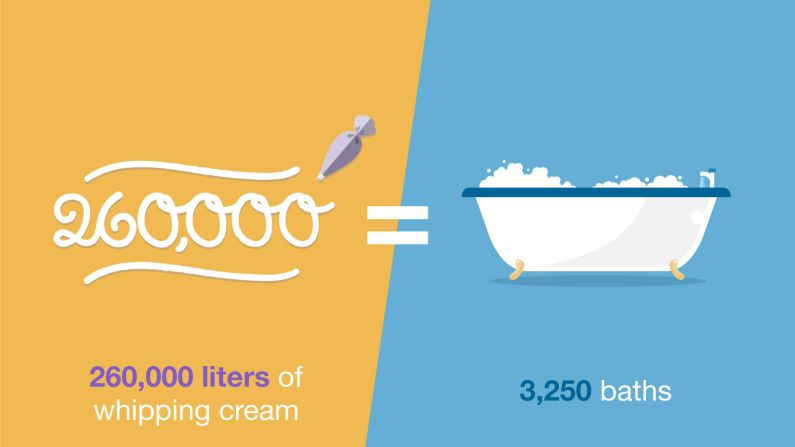

Emirates and Crop One say the facility will use 99% less water than outdoor fields, and once completed, aims to harvest 6,000 pounds of leafy greens daily, which will find their way into both in-flight meals and airport lounges from December next year.

Is the great indoors the future of farming?

It’s estimated the UAE imports as much as 85% of its food needs and only a small percentage of land is considered arable. Hyperproductive indoor vertical farming built close to the consumer is therefore an appealing concept on paper.

The process is “season-less” and grows produce 365 days a year. Plants feed on a nutrient solution instead of soil, and variables including temperature and humidity are tightly controlled in modular containers to generate maximum yield. Instead of the sun, LED grow lights are used.

Saeed Mohammed, CEO of Emirates Flight Catering, says the move “secure(s) our own supply chain of high quality and locally-sourced fresh vegetables, while significantly reducing our environmental footprint.”

Critics of vertical farms argue that they have high energy requirements. However, their carbon footprint can be reduced by powering them using renewable energy sources, and by increasing the efficiency of their LED lights.

Crop One confirmed its upcoming facility will use “a mix of renewable and utility source” electricity, and is targeting solar energy.

Leo Marcelis, professor of horticulture and product physiology at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, an academic unattached to the project, said there is a lot of research in the field into decreasing energy use in vertical farms.

“Lighting companies are working on LED technology to make the conversion of electricity into light better, and what we are studying is how we can grow plants with less light, or with the same amount of light and produce more plants,” he says. “We expect that systems will get more efficient in the coming years, because it’s all new now.”

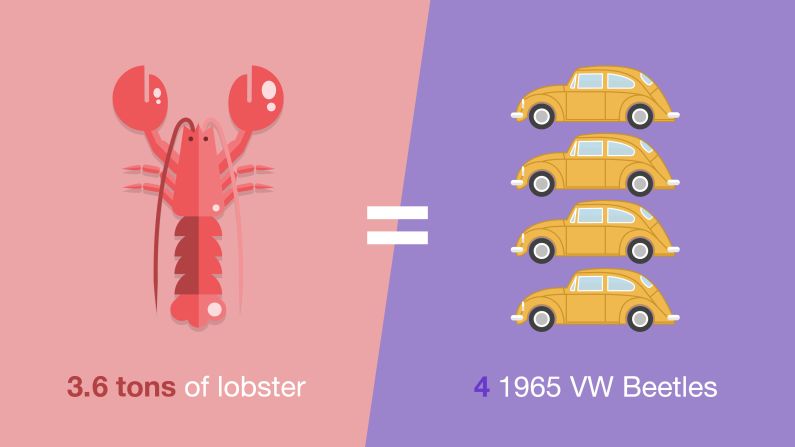

Crop One is far from the only operator in the field of vertical farming, with outposts springing up around the world, many making eye-popping claims. AeroFarms touts an annual production capacity of 2 million pounds of greens from its 69,000-square foot indoor farm in Newark, New Jersey. California-based Plenty claims for certain crops, it can grow 350-times what a field can on the same footprint. Infarm in Berlin builds hydroponic modular systems that have popped up in supermarkets around the city.

Inside the world's biggest airline food factory

Dickson Despommier, author of “The Vertical Farm” and professor emeritus of public and environmental health at Columbia University, says: “To see a major economic player like Emirates Airlines getting involved in an alternative to importing all their food is remarkable. The industry has grown to the point where they can actually do that and expect a return on their investment.”

Despommier adds that while bragging rights to the largest vertical farm have bounced around the world in recent years, size isn’t everything.

“To be honest, who cares who’s the biggest?” he says. “I want to know who’s the most efficient and who’s producing the (widest) diversity of plants that people actually eat, rather than just leafy green vegetables – which is what seems to be the gold standard right now for actually jumping off from non-profitability to profitability.”