Story highlights

The world is better prepared for a similar outbreak than in 2003

Airplane manufacturers are putting more emphasis on inflight air quality

Global response plan and advanced technology for disease tracking

Reality is SARS and similar viruses still scare

In the 2011 suspense movie “Contagion,” Gwyneth Paltrow’s globe-trotting character dies from a virus that stirred up our memories – and fears – of SARS, the respiratory epidemic from China that killed several hundred people around the world in 2003.

Paltrow played Patient Zero, a woman who travels through Hong Kong – where we were treated to scenes of Kowloon, by some accounts the densest concentration of human life on the planet – from where she boards a plane and subsequently spreads the deadly virus around the world.

While the movie was fiction, SARS was very real. It made us feel nervous, vulnerable and afraid.

But it also made us learn.

Exactly one decade after SARS hit, is the travel world ready if a similar epidemic – a SARS 2.0 – were to break out?

Hong Kong's 2003 SARS crisis

Experts in the aviation, hotel and health industries agree we’re now much better prepared than before to deal with such a potential calamity.

SARS -- what have we learned?

But some still prefer to avoid publicly addressing the issue.

Here are five of the most important lessons we’ve learned about handling global epidemics, ten years on.

1. SARS helped the world realize we needed a global plan

“The most important change has been the adoption of the International Health Regulations in 2005,” says Dr. Isabelle Nuttall, World Health Organization Director for the Global Capacities Alert and Response Department in Geneva, Switzerland.

The IHR, as Nuttall describes, is basically one massive global plan that maps an emergency response effort if a health emergency – such as SARS – strikes. At present, 194 states and territories have signed the legally binding agreement.

Ten years ago, a plan like this simply didn’t exist.

“During SARS everything had to be invented,” says Nuttall. “It was the first time we were dealing with such a disease, such an international threat. We had to mount new networks of clinicians and laboratories.”

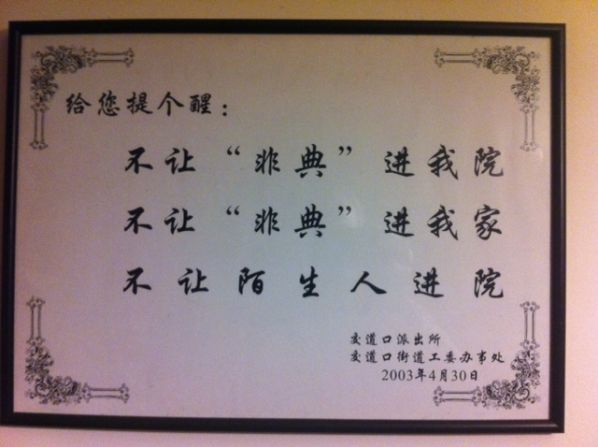

And there was no obligation to report anything quickly – as the world learned from a secretive China in April 2003.

On one Saturday that month, health authorities in Beijing claimed just 37 confirmed SARS cases existed in the capital. One day later, Beijing revealed 346 confirmed cases with another 402 suspected.

The international community condemned China for withholding vital information.

Ten years later, the IHR now gives the World Health Organization “probing powers” into any signatory country to check in and make sure everything is okay. Countries are legally bound to report all they know.

READ: How SARS brought Hong Kong to its knees

2. SARS helped us be more alert with technology and training

While NORAD, North American Aerospace Defense Command, tracks airspace over the United States and Canada for potential threats, the World Health Organization boasts its own global watch system for brewing health crises.

Like a global plan, the capability for high-tech tracking also didn’t exist ten years ago.

“We now have a system that is constantly screening the web 24/7 for information and rumors,” says the WHO’s Nuttal. “We analyze them – and some turn out to be false. However, every single piece of information is touching our attention and bringing the information to a team of people.”

While the World Health Organization has an army of 8,000 health and safety officials, the Kowloon Shangri-La in Hong Kong has an 800-person trained team of employees that both welcome and watch hotel guests.

“We always want to be alert, but we certainly don’t want to be alarming,” says Linda Wan, resident manager at the Kowloon Shangri-La.

The 20-year industry veteran, who moved from the United States to Hong Kong last year, has an old 2003 emergency SARS manual sitting on her desk. That has evolved into a general emergency response manual that the Shangri-La uses to train staff.

Employees are taught to sanitize public areas – elevator buttons, escalator rails, door knobs and restroom doors – every hour or based on foot traffic frequency.

In guest rooms, housekeeping disinfects frequently touched items with special focus on remote controls, light switches and bathrooms.

“If a guest is ill we may refer them to a nearby clinic and notify proper authorities of any heightened concern,” says Wan.

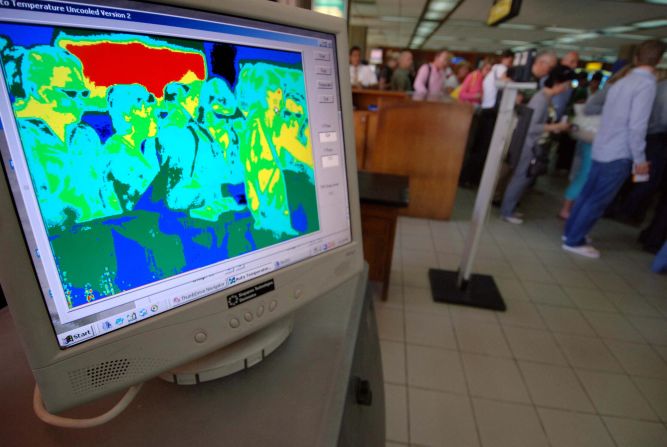

Even before hotel guests check in, thermal imaging technology at major airports serves as an earlier field of defense against visitors arriving with a fever.

The closer your image is to the red side of the visible light spectrum, the warmer you are. Too warm and you get a visit to the quarantine room for questioning and a potential sick bed.

3. SARS taught us to appreciate breathing in deeply

You board your plane, amble down the aisle, spot your seat and then … mentally cringe: your red-nosed neighbor for the next several hours is coughing and sneezing into already-moist tissues.

If air purity is a factor in which airplane you fly, the Boeing Dreamliner (battery problems notwithstanding) is best, according to Tom Ballantyne, the Sydney-based chief correspondent for Orient Aviation.

The two-decade aviation expert says the Dreamliner’s technologically advanced systems mean its air is the best-filtered in the skies.

Another benefit of the state of the art system is a difference in cabin pressure. While other airplanes are pressurized at about 8,000 feet in altitude, the new Dreamliners are pressurized at 5,000 feet, “so it’s a much more pleasant atmosphere.”

Higher humidity levels also keep that dry cottonmouth feeling at bay.

The newer Boeing 777’s and the latest versions of the Airbus A350 and A320 Neo also have well filtered air, adds Ballantyne.

“As newer models come out, their internal air purification systems are more advanced.”

But the 747-400 sits on the opposite end of the clean air spectrum because it’s “a relatively elderly aircraft” that’s been in operation for nearly three decades, says Ballantyne.

While Singapore Airlines retired its last 747 passenger jet in April 2012, Hong Kong-based Cathay Pacific still has 18 in its fleet, United Continental operates 23 and British Airways boasts to be “the world’s largest operator of the Boeing 747-400” – with 57 aircraft.

READ: Hong Kong housing estate became ‘ground zero’

4. SARS taught airlines to be financially more resilient

Between 2001 and 2005, an average of more than one major U.S. airline filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection each year: TWA (2001), US Airways (2002) , United Airlines (2002) , US Airways again (2004) and both Northwest Airlines (2005) and Delta (2005) on the same day in a coincidence in timing.

But from 2006 onward, just one major U.S. airline filed for bankruptcy protection – American Airlines in 2011.

The reason is that catastrophic events, such as 9/11 and SARS, taught airlines an important lesson.

When people stopped flying, “airlines recognized the thing that gets them into real trouble is running out of cash,” says Paul Sheridan, head of consultancy Asia at Hong Kong-based Ascend. Airlines learned to “make sure they have enough cash flow” to weather turbulent times.

“Over the last five years, we’ve seen oil prices hit 150 bucks a barrel, swine flu and a volcanic ash cloud” that all impacted air passenger numbers, says Sheridan.

“The industry has had plenty of practice and (now keeps) more cash on hand. It’s a pretty wide range for liquidity, but perhaps it’s 10 percent of revenue, maybe a bit higher.”

If it hadn’t been for 9/11 and SARS, “a lot of airlines would have been bankrupt now if you threw the same issues over the last five years at them.”

5. SARS – and other big, bad diseases -- still scare us

Sometimes what we learn isn’t through what is said, but through what is not.

Although SARS occurred a decade ago, an inordinate number of people and businesses declined comment for this article – including all four international airports in the SARS hub cities of Hong Kong, Beijing, Singapore and Toronto.

“The responsible person has a very full schedule recently – sorry,” texted Hong Kong Airport Authority spokeswoman Chris Lam.

“This is something that we’d rather not revisit at this point in time,” e-mailed Robin Goh, assistant vice president of corporate communications at Singapore’s Changi Airport Group.

Beijing Capital Airport authorities told CNN it would take “several days to look at an application” for an interview after having been closed the entire week prior for Chinese New Year.

Toronto Pearson never replied to e-mailed interview requests.

“I don’t know why (they would not talk) to tell you the truth,” said Ballantyne of Orient Aviation. “I could understand the trouble with Beijing and bureaucracy, but I would have expected Singapore and Hong Kong to be willing to talk about it. You fly to Singapore and you can still see the signs and huge thermal imaging cameras. I’d be happy to say ‘We’ve got these things.’”

In the hotel industry, similar caution appeared to exist.

Hong Kong’s Kowloon Metropark (formerly the Metropole), the Hong Kong hotel that had the first reported SARS case in the city, declined an interview request.

“I’m sorry we do not want to put out any comments on the SARS issue because we want to look forward,” said Anita Kwan, public relations manager at the Metropark Hotel in Kowloon. “I have spoken to the boss.”

The Hong Kong Four Seasons, arguably the city’s top hotel, also declined to discuss any precautions and response procedures it had in place.

“Feburary is our peak season and we are too busy to arrange any interview at this moment,” said Angela Wong, the Four Seasons public relations manager.

And international airlines including Singapore Airlines, Cathay Pacific and Emirates Airlines all either stopped communicating, only released statements or declined interview requests through their public relations agency.

The lessons learned 10 years later? We have a global response plan and advanced technology for disease tracking. And we have better training for hygiene and healthier airline financial strategies.

Yet while we’re much better prepared, SARS still scares us … sometimes into silence.