Out of a job, Gadhafi's Tuareg fighters may create new troubles

- Nomadic people had served in Gadhafi's army

- Experts worry they may start revolts in Mali, Niger, Chad

- Human rights groups are calling for no revenge against Tuareg in Libya

(CNN) -- They are the Kurds of Africa, an ancient stateless people with their own language, a minority spread across several countries, weathered by their harsh surroundings.

And like the Kurds, the Tuareg are now at the center of international attention. Some are helping Moammar Gadhafi loyalists escape Libya across the endless expanses of the Sahel. Many more are trapped in Libya, trying to escape its post-revolutionary chaos.

Gadhafi often turned to the nomadic Tuareg to bolster his forces and his attempts to manipulate and destabilize the poor countries to the south of Libya: Niger, Chad and Mali. The Tuareg were capable mercenaries. And there was a hint of romance in the arrangement -- Gadhafi has always painted himself as a desert Bedouin.

Peter Gwin, a journalist with National Geographic, has visited Tuareg areas of Mali and Niger frequently. He says one Tuareg who had visited many Libyan army bases told him that even before the uprising against Gadhafi began there were some 10,000 Tuareg fighters in the Libyan military.

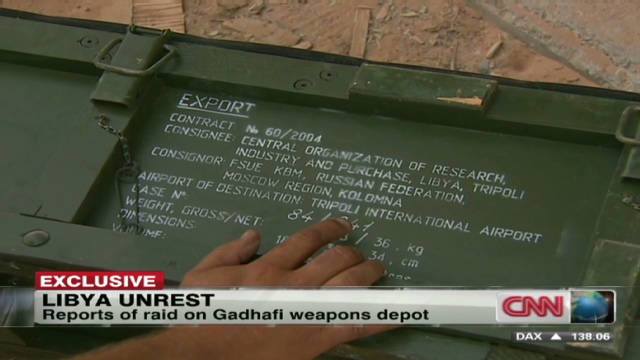

Libyan weapons stash ransacked

Libyan weapons stash ransacked

Inside a Gadhafi safe house

Inside a Gadhafi safe house

Does Gadhafi have any friends left?

Does Gadhafi have any friends left?

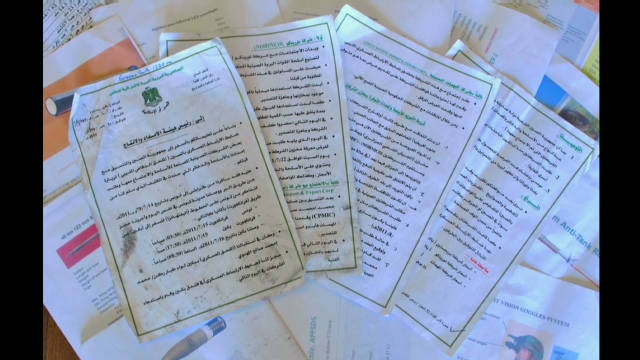

Libyan documents reveal 'secrets'

Libyan documents reveal 'secrets'

For the Tuareg it was a marriage of convenience; they could send money home and received arms and money for their rebellions. Gadhafi long supported the Niger Movement for Justice, a Tuareg rebel group, and gave its leaders villas in Tripoli.

As the revolt against his rule began, Gadhafi sent recruiters to Mali and Niger. Gwin says they were reportedly offering $1,000 a month to Tuareg recruits, an incredible sum in an area where the average income is less than $1 a day. Hundreds signed up.

One fighter Gwin met in the Malian city of Timbuktu described being involved in carrying out Gadhafi's order to "clean" the city of Misrata, a rebel stronghold.

"I asked him did that actually happen," said Gwin, "and he said half of Misrata was cleaned. ... and I said what about civilians? And he said: 'Everyone.' What about women and children? And he nodded and said: 'Yes.' "

But Tuareg fighters told Gwin that Gadhafi had failed to deliver on many promises -- of cash, homes and cars. And they were not expecting to be bombed from the air. Many deserted and began the long difficult journey home across the Sahara and arid mountain ranges, avoiding checkpoints as they went.

The danger now is that many of them -- young, jobless men -- will rekindle simmering revolts. In Niger the rebels control swathes of territory.

Gwin describes it in September's edition of National Geographic magazine as "a vast primordial landscape -- a place defined by salt pans that take the better part of a day to cross, dune fields that rise and fall like violent seas, and mammoth outcroppings of glassy marble and obsidian that breach the sand like extinct sea creatures."

The Tuareg trust few outsiders. Gwin says it is not only to combat the elements that the men cover their faces with turbans, and they are guided by a proverb: "Kiss the hand you cannot sever."

But since Mali and Niger gained independence, the Tuareg have been neglected and marginalized. In Niger, the Tuareg complain that they have no schools or wells -- even as governments have raked in millions from rich seams of uranium.

That was the spark for the most recent revolt. Not all Tuaregs supported it; there are disparate factions and clans. Even so, the governments of the Sahel -- especially Niger -- are shuddering at the prospect of well-armed fighters returning to their unstable countries.

A group of prominent Tuaregs from Niger and Mali has appealed to Libya's National Transitional Council to protect those Tuaregs still in Libya. Mohamed Anacko, head of the Agadez Regional Council in Niger, told CNN that they "wanted to avoid a crisis like in Libya here at home. So (we wanted) to make a contract between those who fight, who are in the Libyan army and the NTC."

Niger and Mali are very fragile states, Anacko said by phone from Agadez. "There really is a risk of famine this year. There are lots of people who are arriving, some are transferring to West Africa but (others) are remaining in Agadez some months. ... so we have lots of worries this year, in the next three to four months."

Human rights groups have also called on Libya's new rulers not to seek revenge against the Tuareg and other Africans, to prevent a further flood of refugees. Niger -- in the grip of a prolonged drought -- is already struggling to absorb as many as 200,000 of its own citizens who have returned from Libya, according to the European Union's counter-terrorism co-coordinator, Gilles de Kerchove.

There is also the risk that renewed instability in the region will play into the hands of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), one of the group's fastest-growing affiliates, which has made a lot of money from kidnap ransoms.

Terrorism analysts say AQIM may already have obtained weapons looted in Libya's chaos. Nigerien forces were involved in a shoot-out in June against an armed group carrying detonators, explosives and cash. The government said they were destined for AQIM.

Anacko told CNN that his group was trying to help Libyans and others who were trying to escape the fighting, to prevent al Qaeda from taking advantage of the situation. "If we don't help them, it is certain that al Qaeda will take them," he said. "We open the door, weapons or not, they give away their weapons and they go back."

The Tuareg are not Arabs and have little sympathy for al Qaeda, but their paths may cross in the flourishing drugs trade in this part of Africa. The Tuareg have a reputation for doing business with anyone.

In his National Geographic piece, Peter Gwin relates a conversation with a Tuareg rebel commander who said the West should help them combat al Qaeda and drug smugglers. "Given the Tuareg history of betrayal and infighting," Gwin asked him, "could the West trust them?"

"He answered with a click of his tongue. I couldn't gauge his expression because his face was completely obscured by his turban."