Story highlights

President Fernández has said Argentina would keep paying "as befits a country which has recovered its self-esteem"

New York Judge has ordered Argentina to make the escrow payment as it is due to pay over $3bn in restructured debt

A US appeals court has put on hold a New York judge’s order for Argentina to pay $1.3bn into escrow for holders of its defaulted debt by December 15, quelling fears of an imminent default.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals granted the stay and set a hearing for February 27. There was no immediate reaction from the Argentine government.

Last week, Judge Thomas Griesa of New York ordered Buenos Aires to make the escrow payment at the same time as it is due to pay more than $3bn to holders of restructured debt.

The government had requested the stay in an emergency motion filed late on Monday and has since floated the idea of asking congress to lift a so-called lock law in order to reopen a debt swap to holdout creditors led by the US fund Elliott Associates, but with a tough writedown.

The holdouts refused debt swaps in 2005 and 2010, which restructured about 93 per cent of the almost $100bn on which Argentina defaulted in 2001. The government is barred by law from making them any better offer.

“We are waiting for the appeals court decision. Until there is a decision on the matter, we have nothing to add to what we have said in recent days,” Hernán Lorenzino, the economy minister, told reporters hours before that court ruled.

The court said Argentina must now file papers by December 28. Amicus briefs and papers from other interested parties – including holders of restructured debt led by Gramercy and including Brevan Howard, one of the world’s biggest hedge funds – are due by January 4.

The Elliott-led parties then have until January 25 to make their case and Argentina has until February 1 to reply before the hearing. After December, Argentina’s next payment on its restructured bonds is due in March.

“The Second Circuit’s order signals its understanding of the serious constitutional and equitable issues at stake,” said Sean O’Shea, a lawyer for the exchange bondholders. “The stay issued late today ensures that the exchange bondholders will receive their rightful payments through December, and the court can carefully consider the significant issues and interests that are involved before rendering its final ruling.”

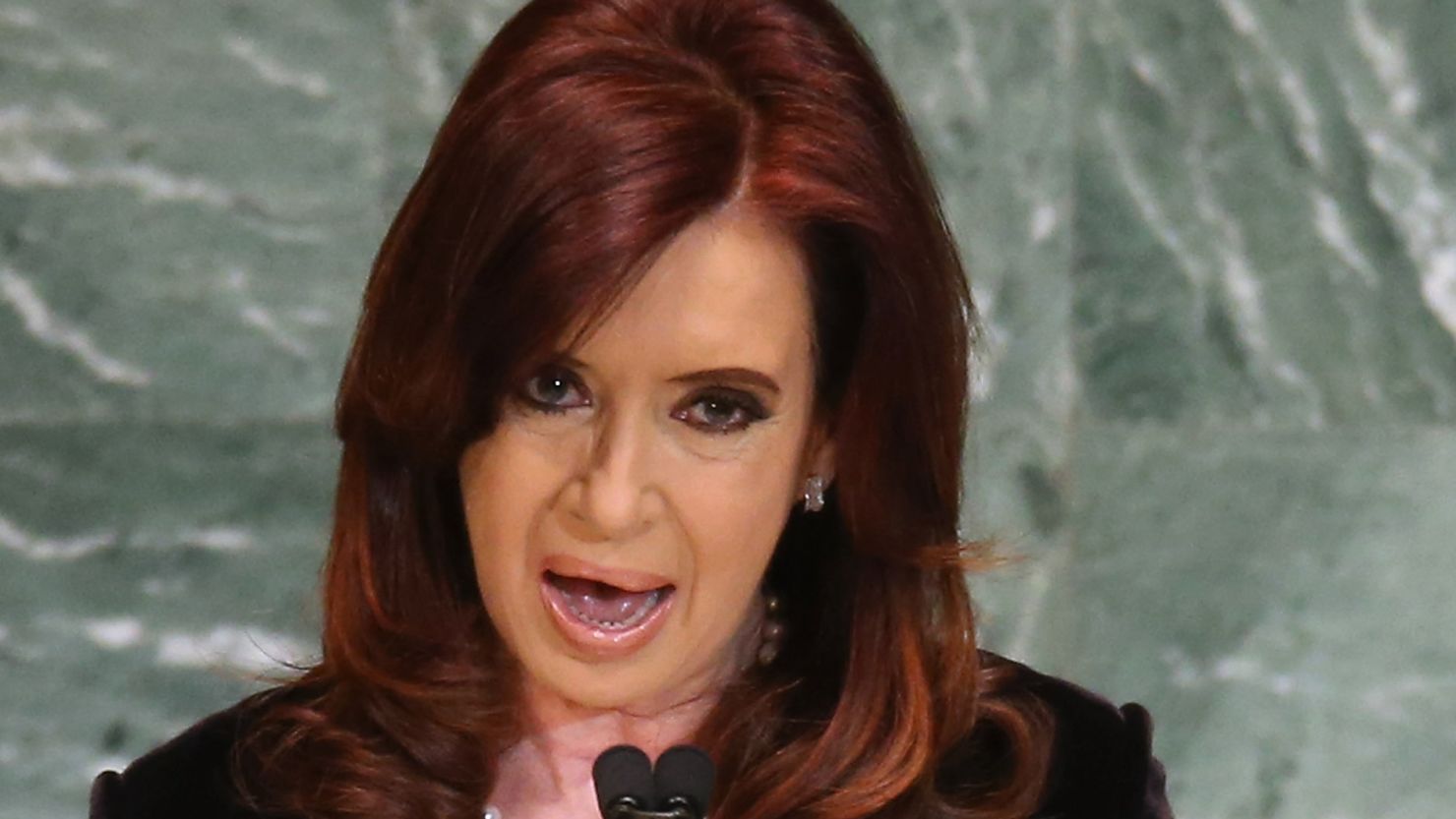

President Cristina Fernández had earlier said Argentina would keep paying. “When the swap was last opened, we reached 93 per cent acceptance. We have paid on time since 2005, without access to the [international] capital market, with our own resources. And we are going to continue to do so because we are going to honour our commitments as befits a country which has recovered its self-esteem,” she told an industrialists´conference also attended by President Dilma Rousseff of Brazil.

Argentina’s suggestion that it could reopen the swap again was greeted enthusiastically by political and business leaders at home. Analysts say it is a belated concession to “vulture funds”, to whom the government has until now vowed never to pay a dime.

But it is not one that will necessarily sway the court, let alone the “holdouts” who spurned the two previous offers. Nor is it likely to resolve an intractable dispute that threatens to trigger a new default. Indeed, on Tuesday Fitch Ratings slashed Argentina’s sovereign credit rating five steps to CC from B on “increased probability” of a default.

Adam Lerrick, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) think-tank and former chief negotiator of the Argentine Bond Restructuring Agency, the nation’s biggest creditor in the 2005 swap, said: “Simply reopening the exchange is unlikely to satisfy the court’s concerns. The holdouts will not accept a reopening. A reopening is simply a way to show that the holdouts have not been disenfranchised of their rights.”

Argentina passed the lock law at the end of 2004 to twist bondholders’ arms to accept a tough restructuring in 2005 that offered about 30 cents on the dollar. Holders of about three-quarters of the almost $100bn on which Argentina defaulted in 2001 took the “haircut”.

But with a chunk of debt still outstanding and increasing holdout litigation, Argentina suspended the lock law at the end of 2009 and reopened the exchange. After two good-faith offers, the government considered the holdouts history.

Ms Fernández said a ruling that did not take account of the 93 per cent was “absolutely inequitable”. She said Argentina had become a “countermodel” to the International Monetary Fund´s recommendations “in a world in which financial capital and its derivatives have set themselves up as masters . . . and want to punish us¨.

Miguel Kiguel, an economist, said talk of lifting the lock law was “obviously coming a bit late. . . They only did it now because they´re on the ropes”.

If Argentina does end up having to pay the holdouts more than the restructured creditors, it could trigger more litigation. But as Mr Lerrick noted: “The ‘most favoured lender provision’ of the new bonds expires on December 31 2014. From January 1 2015, Argentina can settle with the holdouts without any obligation to pay additional amounts to the exchange bondholders.”