Story highlights

Former FBI agent says he wanted Bulger cut off, but there was nothing he could do

The prosecutor uses the former agent's book to challenge his version of events

The defense attorney's request for sequestration is denied

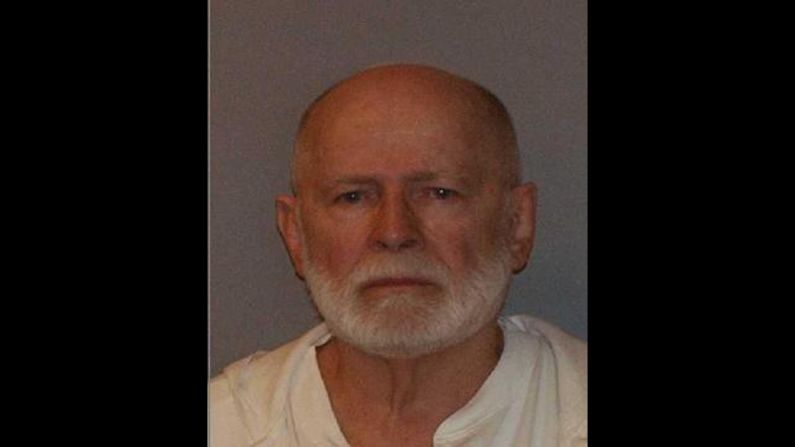

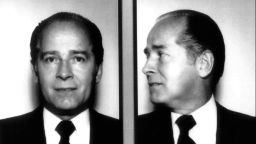

Bulger is accused of participating in 19 murders and faces other charges

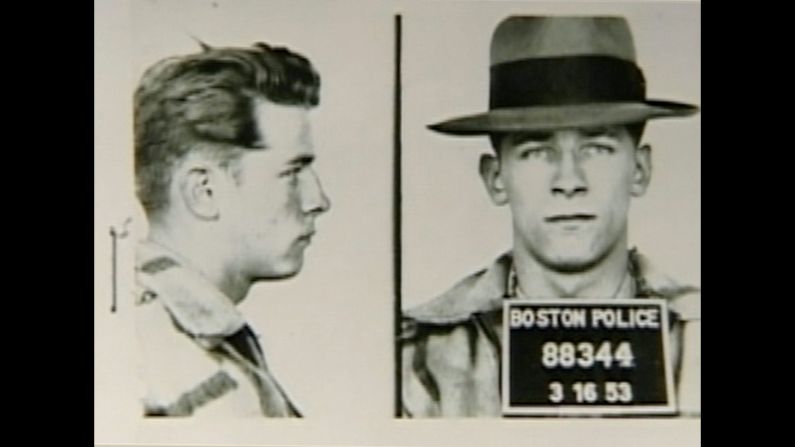

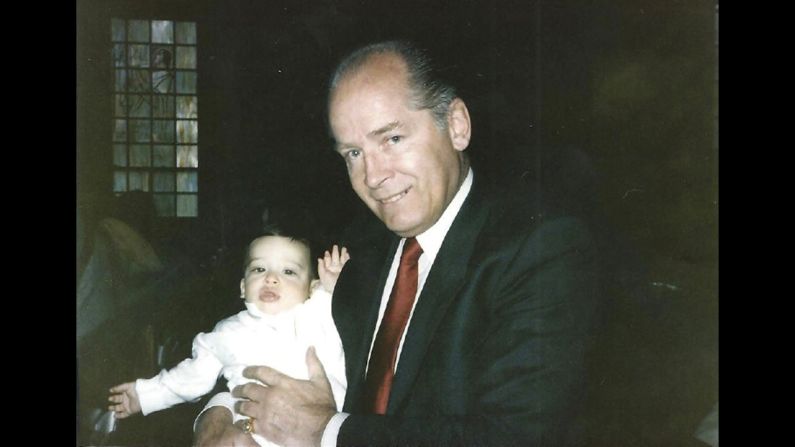

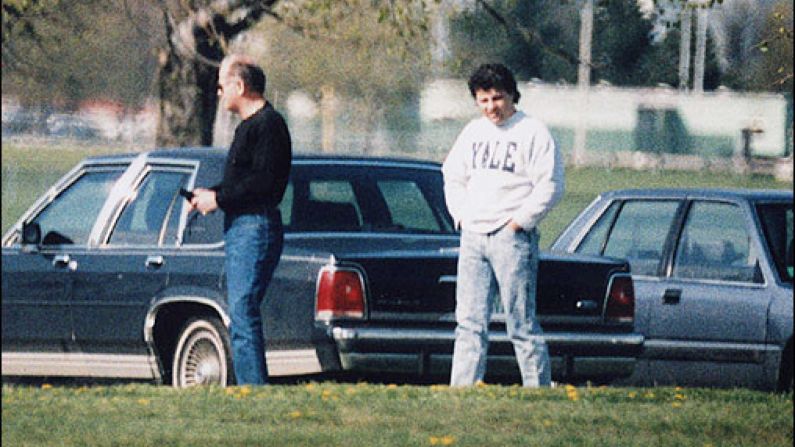

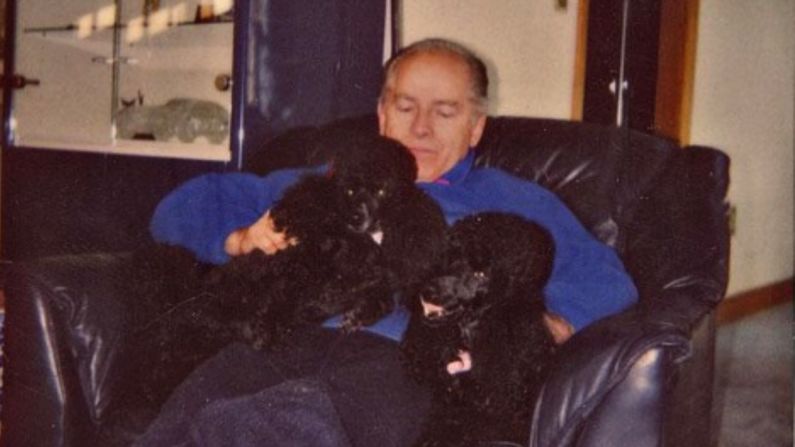

An FBI official assigned to Boston to clean up corruption in the 1980s testified Tuesday he was overruled by his superiors when he suggested decades ago that James “Whitey” Bulger be shut down as an FBI informant.

“They didn’t do it. I didn’t like it, but there was nothing I could do about it,” said Robert Fitzpatrick, the former assistant special-agent-in-charge of the Boston office, who testified his bosses at FBI headquarters in Washington “felt Bulger was the person who was going to bring down the Mafia.”

Prosecutors have charged Bulger with participating in 19 murders in a 32-count indictment that also accuses the alleged Boston Irish mob boss of racketeering, money laundering, and extortion during some two decades.

Defense witness testifies Bulger didn’t seem much of an informant

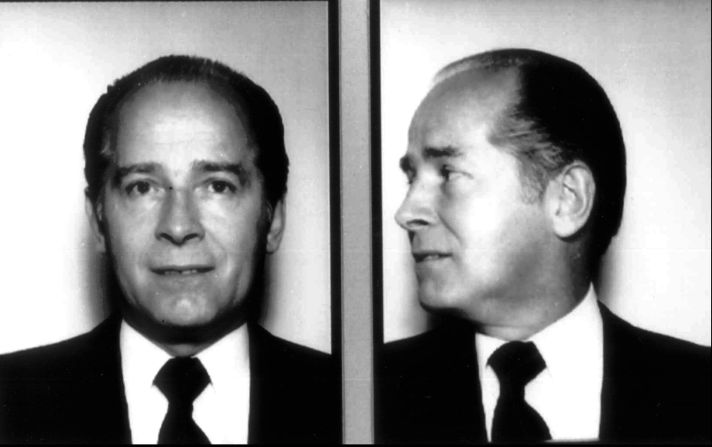

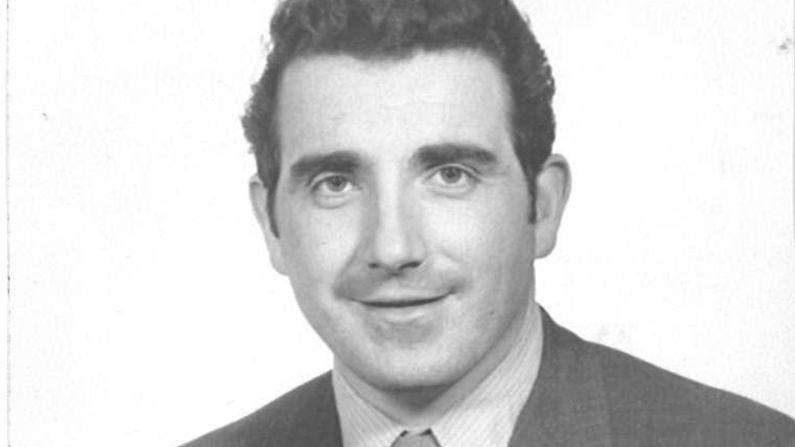

During that time, according to previous testimony from a disgraced former FBI agent, Bulger was also an FBI informant instrumental in the takedown of the New England Mafia, La Cosa Nostra.

Fitzpatrick, who was in charge of the drug task force in the organized crime squad, said he was not more forceful in pushing to cut off Bulger as an informant because of the FBI’s “quasi-military” structure, saying it would have been a “violation of protocol” to take his concerns any higher.

He testified that his recommendation on Bulger came after a 30-minute meeting in which Bulger did most of the talking.

Even though he was the second-highest-ranking agent in Boston at the time, Fitzpatrick played down the scope of his authority, suggesting he was undermined by Bulger’s FBI handlers, apparently unaware at the time that they were being paid off by Bulger.

But Fitzpatrick testified Monday that during the 30-minute meeting, Bulger indicated that the FBI wasn’t paying him, but that he was paying the FBI. Asked why he didn’t investigate the alleged bribery, Fitzpatrick said, “It could just be a pay-off … no quid pro quo.”

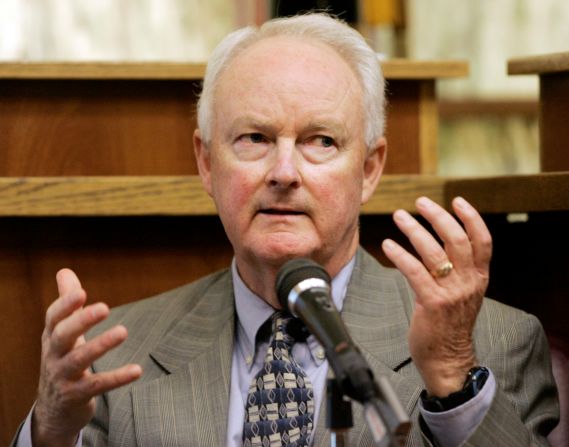

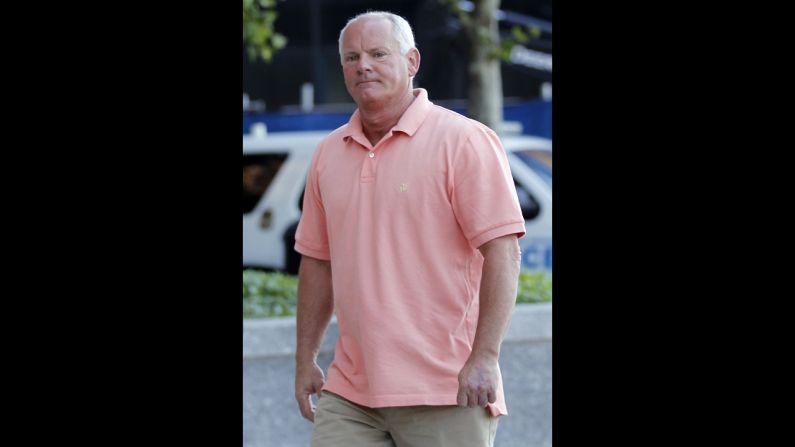

Prosecutor Brian Kelly suggested Fitzpatrick was not interested in shutting down a bad informant: “Weren’t you more concerned about your own bureaucratic career than rocking the boat?”

Trying to discredit Fitzpatrick’s story, Kelly read passages from his book, “Betrayal,” in which the former agent recounts events at which he was not present. Kelly accused him of creating “an entire imaginary conversation with James Bulger,” and smirked at the notion Fitzgerald “taunted” the reputed crime boss.

Although the book is portrayed as “absolutely true,” its copyright page lists it as “fiction.” On the stand, Fitzpatrick described it as a “memoir, a recitation of things” he believes happened.

His goal, he said, was to expose corruption in the FBI, which is also, he says, why he resigned: “I didn’t want to be part of the corruption.”

During cross-examination Tuesday, Fitzpatrick had difficulty remembering his testimony from the previous day.

“Do you have trouble with your memory?” the prosecutor asked.

“Not that I recall,” answered Fitzpatrick, drawing some quick laughs from the court.

Bulger’s defense attorneys called Fitzpatrick as part of their attempt to highlight corruption within the FBI during the 1970s and ’80s.

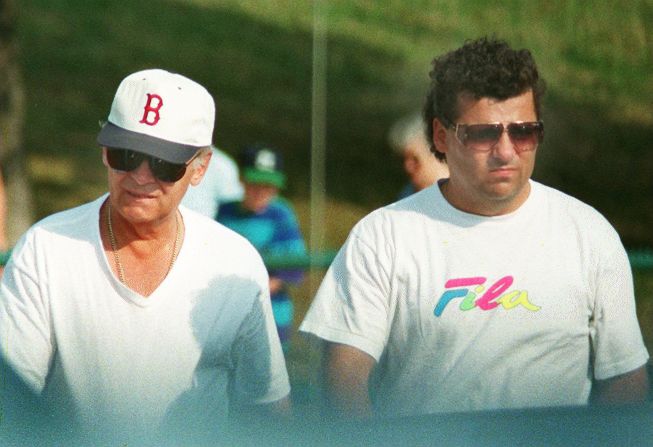

Another witness testified that rogue FBI agent John Connolly had access to all FBI informant files and therefore to the identities of everyone cooperating with the government.

One of them was alleged Bulger crime associate Brian Halloran. Fitzpatrick previously testified he went to strike force attorneys requesting the Justice Department be more diligent about putting Halloran in witness protection.

Halloran was cooperating with law enforcement and had implicated Bulger in the murder of a wealthy Oklahoma business man. Two days later, Fitzpatrick testified, Halloran was shot to death. Bulger’s former associate Kevin Weeks previously testified that Bulger fired a machine gun in the hit, along with another shooter.

Pointing to Judge Mark Wolf’s portrait in court, Kelly argued that in 1988, during hearings before Wolf, Fitzpatrick could not recall going to the Justice Department to help get Halloran in witness protection.

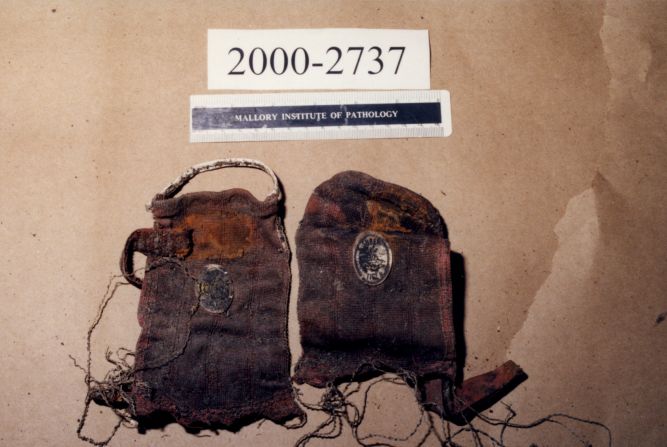

The prosecutor also zeroed in on a passage in the memoir in which Fitzpatrick suggests he was present in 2000 when the body of another alleged Bulger victim, John McIntyre, was pulled from the “frozen ground.” Despite writing that the image was “etched in my memory,” Fitzpatrick couldn’t recall whether he was actually there.

Fitzpatrick was not working for the FBI at the time McIntyre’s remains were exhumed in 2000.

“You were trying to take credit for something you didn’t do,” Kelley said.

The prosecution alleges Bulger ordered a hit on McIntyre, a fisherman, after learning that McIntyre was cooperating with law enforcement on the investigation of a shipment of arms Bulger intended to send to the Irish Republican Army on the fishing trawler Valhalla.

McIntyre also tipped authorities to a 36-ton delivery of marijuana on the boat Ramsland in 1984, months before he was killed, prosecutors say.

Developer describes threats in trial

Kelly brandished documents in court that showed Fitzpatrick vouched for rogue FBI agents during the same time he claims he complained about their behavior. Fitzpatrick apparently signed off on glowing FBI evaluations of disgraced and now-jailed Connolly, and even signed off on a recommendation for him to go to a Harvard program.

On redirect questioning, Fitzpatrick defended his book to the jury.

“The book is about the criminal justice system,” he said. “In my estimation the criminal justice system failed, it failed during this whole situation. I wanted to bring it to light, not just for the public, for my family.”

Fitzpatrick, who is still fighting to receive the full amount of his pension, plans to write another book on this trial, he said in court.

Jury will not be sequestered

Despite a request by the defense, Judge Denise Casper decided Tuesday not to sequester the jury, saying this late in the trial the jury was unprepared, and it could be prejudicial to both sides to have a disgruntled jury.

Defense attorney J.W. Carney previously argued that there has “never been a more widely publicized or sensational case in this district,” saying there has been saturated media coverage and “statements that are so hyperbolic and prejudicial towards the defendant … unlike anything anyone has seen.”

The judge said her initial instructions to the jury have been reinforced “more importantly by my repeatedly advising them that they not pay attention to media accounts.” She also said she does not expect a “great amount of coverage during deliberations.”

“We have to assume the jurors are following my instructions,” she said Tuesday morning.

“I am not inclined to inconvenience these jurors at this juncture,” she said, particularly when they have had “no notice” of the potential of sequestration.

The defense has so far called two of its estimated 15 witnesses. It took the prosecution 30 days and 63 witnesses to present its case, which it wrapped up Friday.