Editor’s Note: In this series, CNN investigates international adoption, hearing from families, children and key experts on its decline, and whether the trend could – or should – be reversed.

Story highlights

Fight to end adoptions from South Korea being led by U.S.-Korean adoptees

South Korea pioneered international adoptions in the wake of the Korean War

As recently as 2005, South Korea was among the top nations for sending orphans abroad

U.S. adoptees have returned to Korea to try to improve rights for single mothers

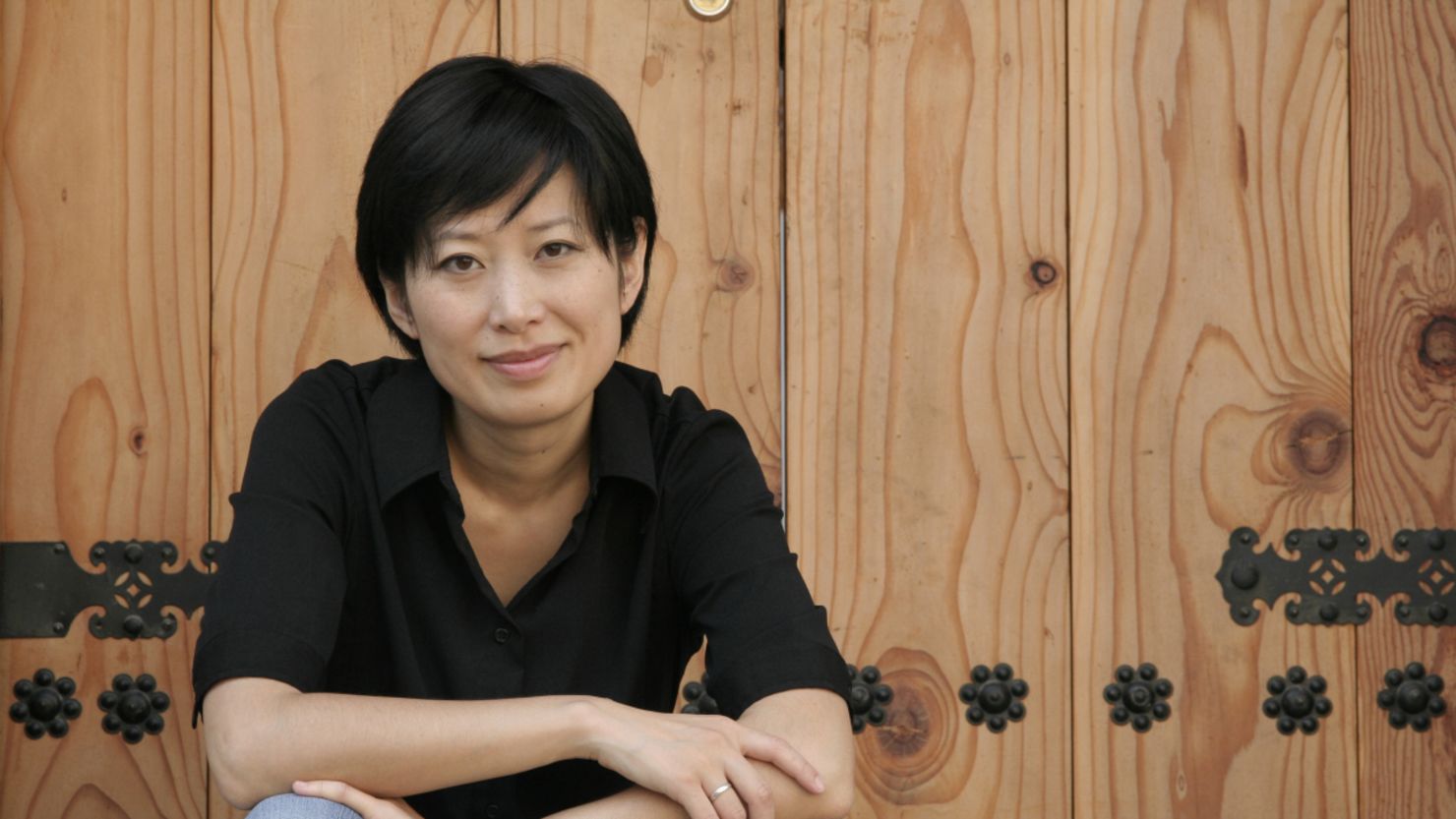

Jane Jeong Trenka, adopted from Korea at the age of six months in 1972, never felt she belonged growing up in a rural Minnesota town. But decades later the 40-year-old discovered her adoption began with a lie.

While trying to apply for a visa in 2006, Trenka was told her legal birthday didn’t match birth papers supplied by her orphanage. After an investigation, Trenka unraveled the mystery: an adoption agency in Korea had given her a fake identity to make her more attractive for adoption, she said.

“I could see where they lied to get me adopted,” said Trenka. Her family history and physical description was rewritten to hide the fact that she was in poor health, having been abused by her father. And the agency had lied to Trenka’s Korean mother, saying she would be sent to a pair of wealthy Dutch lawyers.

South Korea was a pioneer on international adoptions. In the aftermath of World War II and Korean War, more than 200,000 children were sent to live with families abroad, according to the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. As recently as 2005, South Korea was the fourth largest provider of children to U.S. families, sending more than 1,600 orphans that year, according to the U.S. State Department.

But Trenka, who repatriated to South Korea in 2008, is part of a vanguard of American adoptees who have led the fight to stop overseas adoptions from Korea and change the cultural stigma tied to unwed mothers. “The best option is always for a child to be parented by his or her birth parent,” she said. “Then domestic adoption, and only then intercountry adoption.”

“If you take a look at what’s going on in (Korean) adoption reform, all of it is led by adoptees,” said Kevin Haebeom Vollmers, a 36-year old Korean adoptee in Minnesota and publisher of Gazillion Voices, an online magazine on adoption issues. “We’ve been disenfranchised for so long, and we’re finally writing our own history, for the first time, on our own terms.”

In 2012, the Korean National Assembly implemented the Special Adoption Law, crafted by Trenka with a coalition of adoptee activists and allies. The law explicitly discourages sending children abroad.

Under the law, birth mothers must nurse babies for seven days before the child can be considered for adoption. If a mother chooses adoption, her consent must be verified and her child’s birth registered. Finally, a mother may choose to revoke the adoption up to six months after her application.

“It’s a paradigm shift,” Trenka said. “We’re checking to make sure things are done ethically and properly. In my generation, people did things with blindly, deadly, and unethical speed.”

Even before the new law took effect, the number of children being adopted abroad from South Korea has been in decline. Only 621 South Korean children were adopted by U.S. families in 2012, compared to nearly 1,800 in 2002, according to the U.S. State Department.

‘Ungrateful’

Not all adoptees are cheering the reform.

Steve Choi Morrison, 57, is a defender of intercountry adoption and the founder of the Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea (MPAK). “God came down to adopt human beings as his own children, even when we did not deserve it,” he said. “I believe it is our human duty, that if we have more than people from other nations – then we should share.”

Born in the aftermath of the Korean War and orphaned at age 5, Morrison spent his early childhood wandering streets and sleeping under bridges, he said. After moving to an orphanage, he was finally adopted at age 14 to a Christian family in Utah. “They didn’t have to adopt me, but they did,” he said. “I really, really love them for what they did.”

He opposes the new Korean law’s requirement for mothers to register their children’s birth before adoption, arguing that it counters cultural norms. “In Korean culture, face-saving is very important,” he said. “Mothers are afraid the birth record will later show up, and that husbands will not marry them later. If you force birth mothers to register for adoption, they’re just going to abandon their children.”

Korean adoption activist Kim Stoker, 40, disagrees. Morrison’s criticism is based on “incorrect information,” said Stoker, who was adopted as an infant in 1973 and returned to live permanently in South Korea in 1995. “After a child is placed in a family, that child will be removed from the birth mother’s registry.”

Stoker rejects the idea that the law is not suitable for Korean culture. “There’s the idea that Korean culture, as large as it is, and as vast as it is, is somehow static. That is not true. I’ve lived in the country since 1995, and there’s been tremendous cultural change.”

Fight for single-mother rights

Korean returnee activists are now fighting to improve government support for single women who have children. “Mothers are mothers,” she said. “If you give them a real chance, most will want to parent their children. Who is the parent should not be a contest of who has the most stuff.”

Stoker believes South Korea’s adoption reform movement will set an example for other countries. “We’re the first generation of international adoptees that are telling our own stories,” she said. “A lot of the adoptees leaving China, for example, are going to look at our model to see what’s important.”

But Jane Trenka said she’s not ready to celebrate. Single mother welfare remains lacking and adoption agencies as well as groups like Steve Morrison’s MPAK are fighting to overturn the Special Adoption Law.

“The Koreans have a saying, after a mountain, there’s another mountain,” she said with a sigh.