Story highlights

Twitter co-founder Biz Stone has launched a new social search engine, Jelly

Stone also has a book coming out next month about harnessing creativity

Stone: "We've become the most connected humanity that's ever existed"

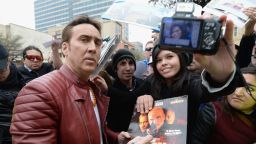

Entrepreneur spoke to CNN at South by Southwest this week

At 9:45 in the morning after his 40th birthday you might expect Biz Stone, best known for co-founding Twitter, to be a little bleary. After all, many millionaire tech execs flaunt their party lifestyle like a badge of honor.

But on this Tuesday, in a quiet corner of an Austin hotel lounge, Stone is clear-eyed, animated and apparently hangover-free.

For the first time in years he’s back at the South by Southwest Interactive conference, where Twitter first and famously blew up in 2007. Stone’s got a book coming out next month, “Things a Little Bird Told Me,” which he describes as “packed with aspirational lessons that were learned through embarrassing mistakes.”

And he’s recently launched his newest venture, a mobile tool called Jelly. Part social app, part visual search engine, Jelly lets users mine their social networks for answers to such questions as, “What kind of plant is this?” or “How do I hook up this TV?”

Jelly is unusual in that instead of computer algorithms like Google’s, it relies on human knowledge to help users find the answers they seek. And each question must be accompanied with an image, creating a sort of visual shorthand. Users can even draw over the images with their finger.

Despite its lofty pedigree – its investors include Bono and Al Gore – Jelly has baffled some tech pundits who don’t understand why people would use it when they can just poll their friends directly through Facebook or Twitter. But Stone, who also helped launch Blogger, remains optimistic that Jelly will catch on.

The serial entrepreneur sat down with CNN at SXSW for a chat about Jelly, social networking and why seeing Twitter hashtags sometimes seems “surreal.” Here’s a condensed version of our conversation:

On bringing Twitter to SXSW:

“Twitter exploded here. It was a watershed moment for Twitter, and it was an eye-opening moment for me. So for the most part after that year I never came back, because I didn’t want to jinx it.

“When we came to SXSW in 2007 it was the first time we could really see Twitter being used in the wild. There was a concentration of people, and most of them were using it. And I saw that Twitter was far more powerful than I realized.

“The one example that comes to mind is … there was this guy in a pub. And he said (on Twitter), ‘This place is too loud for us to talk. Let’s go to this other place.’ And he named it in his tweet. And in the eight minutes it took him to walk over there, it had filled to capacity and there was a line out the door. Twitter took a bunch of loose individuals, and suddenly they became one organism, like a flock of birds.

“And I couldn’t think of another technology that allowed human beings to flock in real time. We went back (to San Francisco), and a few days later we formed the company.”

On the idea behind Jelly:

“We’ve become the most connected humanity that’s ever existed. We’re now connected to anyone else on the planet within four degrees of separation because of social networks and mobile phones. It’s an amazing era of connectedness. And yet not a lot of people stop to think, ‘Why? What’s the true promise of a connected society?’

“I’ve been asking myself that question ever since I left Twitter. And it occurred to me the true promise of a connected society is people helping one other. Or at least it should be.

“So Jelly is a search engine, as audacious as it sounds. Everyone figures we’ve got search all wrapped up. There’s the Internet – it’s vast and growing, and we can search it in a fraction of second to find anything we want. But the Internet is only the Internet … it’s only a collection of documents. There’s way more to life than the Internet. So Jelly is like a search engine for everything else. And the reason it works is that we’re all connected.

“People talk about artificial intelligence. Well, how about (human) intelligence? We have 7 billion people on this planet.”

On why Jelly requires images:

“We’re carrying around 8-megapixel cameras (on our phones). In a world where 140 characters is considered a maximum length, a photo really is worth 1,000 words. For almost any question, a photo can deepen the context. Also, it allows you to type less: ‘Should I buy a Tesla?’ How about just, ‘Should I buy this (with a picture of a Tesla)?”

“A lot of people ask, ‘Why not just ask my social network?’ But what Jelly does is blend Twitter and Facebook together. Jelly gives you far more reach. Your friend’s wife’s lawyer is all of a sudden answering your question.

On how people have been using Jelly:

“Whenever you build something, the creativity in humanity comes out. I love it when I’m seeing answers to questions where people are only drawing on the photo. They’re not even using language. Somebody asked, ‘How do you do a screenshot on a Mac?’ and all the person (answering) did was circle the three keys you touch. It was wonderful.

“I have this theory that if something isn’t fun and goofy, then you won’t use it on a regular basis. And then you won’t think to use it when you need it. The same thing happened with Twitter.”

On the future of social networking:

“Social networking is still brand new. We’re still figuring it out – how much we should share, and how much we should self-edit.

“But I think the bigger thing here is that it’s growing so huge. You can now measure the number of people on planet Earth who use social networking … (as a large percentage) of the planet. And that opens up intense possibilities of cooperation among humankind.

“In the future, what do I think will happen? I think we’ll be able to accomplish in one year what used to take 100 years. Because when people get together and coordinate, they can do amazing things.

On his early days at SXSW:

“I used to come to South by Southwest in the early 2000s every year, and we’d put on a party for Blogger. It (SXSW) always falls on my birthday. So I used to pretend it was my birthday party, because we got Google money to throw around and give everyone free whiskey and beer. And we’d give out Blogger T-shirts, which of course had a B logo, like for Biz. And I’d say, ‘Welcome to my birthday party! Free whiskey for everyone!’ “

On the success of Twitter, which he left in 2011:

“It’s incredibly weird to see, everywhere I look, the little birdie that I drew. Or hashtags on my favorite TV shows. For me personally … that’s surreal. Most importantly, it means that people are finding value in the service.

“And that’s the most important thing you can do in this world before you die – to build something of value.”