Editor’s Note: Eric Liu is the founder of Citizen University and the author of several books, including “A Chinaman’s Chance” and “The Gardens of Democracy.” He was a White House speechwriter and policy adviser for President Bill Clinton. Follow him on Twitter: @ericpliu. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Eric Liu recalls words of civil rights worker before he was shot by KKK gunman

Michael Schwerner told his killer: 'I know just how you feel'

Liu says we should look to empathy as we confront today's divides

I recently read seven words that shook me to the core.

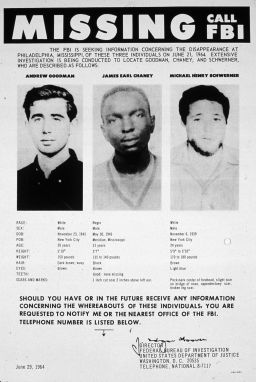

In a mesmerizing interview in the new Smithsonian magazine, the civil rights historian Taylor Branch describes the three Freedom Riders who were killed in Mississippi 50 summers ago.

All three had understood the dangers of going into the Deep South to register black voters. All had been trained in the practice of radical nonviolence. One of them, Michael Schwerner, lived out that ethic as he faced the gun-wielding Klansman who was about to murder him.

Schwerner said to the man, calmly, “Sir, I know just how you feel.” Then the man shot him and his two friends.

Think about that. Put yourself in Schwerner’s shoes. Imagine what it would have taken to summon such stillness, such profound and sincere compassion for one’s killer, at the moment of death.

And then put yourself in the shoes of that Klansman. After all, we know this story only because the Klansman later told it to investigators. He was haunted, for the rest of his life, by the depth of empathy that he confronted in that fateful instant.

This story has stayed with me too, challenging me to admit it when in my comfortable everyday existence I fail to demonstrate even a fraction of that empathy and self-realization.

But it’s stayed with me in my civic identity as well. And it’s made me wonder how much of our political and civic strife could be alleviated if we learned something from a young man who’s been dead a half century but never gave in to fear or hate.

Look around our country today. Look at the New York policemen who feel so insulted that they think they must turn their backs on their mayor. Look at the African-American citizens of that city who feel that the NYPD has never shown them the respect those disgruntled officers now demand.

Look at the online comment threads after Ferguson and Staten Island. Look at how black men in hoodies and white men with badges are demonized.

Look at the escalation of outrage that leads to philosophical hashtag wars about whether #BlackLivesMatter or #AllLivesMatter.

Look at the disgust that drips from the lips of Democrats as they brace for a reactionary GOP Congress and from Republicans as they decry imperious Democrats.

Errol Louis: There are two sides to America’s policing issues

Look now at the people in your own community. Look at the way we walk past people whose circumstances are radically different from our own. Perhaps they are richer or poorer than you, or more liberal or less, or more self-destructive or less. Look at the way we ascribe moral meaning to those differences.

Look at the way we tell ourselves stories about what our selves are. Look at the way those stories always accuse others of faults and excuse us for our own. Look at the way those solipsistic habits, which start with those closest to us, radiate outward.

I have been guilty of this kind of self-justification, both personal and political. So have you. And for all of us, this season is an occasion to ask what it would take to earn the right to say these words:

I know just how you feel.

To some people, this kind of radical compassion and loving nonviolence seems dangerously squishy, a slide down the slope to moral relativism. They fear that understanding the heart of another person, particularly the enemy, will lead to an obliteration of distinctions between self and other, between right and wrong.

But that’s not how it was for Michael Schwerner and for the other Freedom Riders. They had a crystal-clear understanding of the moral differences between them and the last-stand defenders of Jim Crow, between good and evil. Their capacity for empathy empowered them – not to subdue others but to invite them into goodness and thereby transform them.

This power does not come easily. It takes a lot to say truly, in the heat of conflict, that you know how your adversary feels. And to say nothing more – no letting him off the hook, no further demonstrations of your goodness. Frankly, few of us will ever attain the near-saintly disciplined open-heartedness of young Schwerner.

But more of us can come closer. And when few of us even bother trying, we get the political culture of today: polarization for its own sake; politics as a game of annihilation rather than repeat play; citizens as bloodthirsty spectators.

As we begin the new year, as conflicts over race and class and guns and belonging continue to rage across the land, let’s resolve to learn just how someone feels. And to let that knowledge guide our lives as citizens.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.