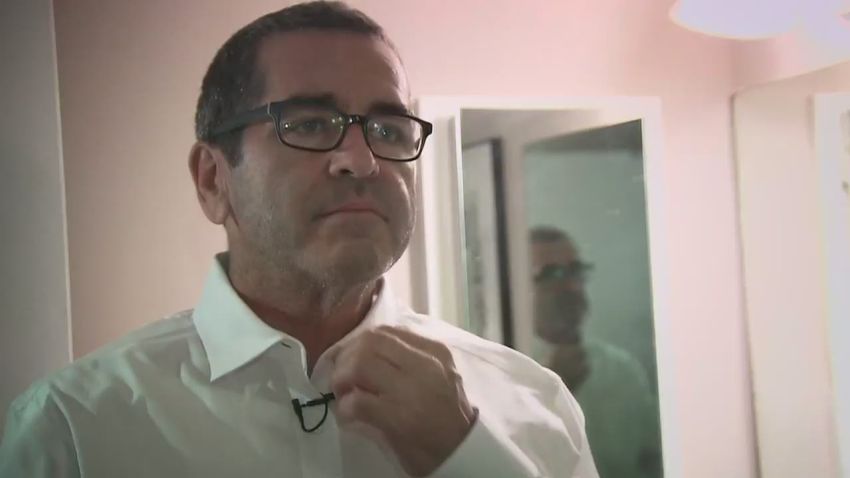

Editor’s Note: CNN contributor Miles O’Brien tells the story of his accident and recovery to Dr. Sanjay Gupta in a special “Miles O’Brien: A Life Lost and Found” at 9 p.m. ET Tuesday on CNN. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Miles O'Brien tells story of recovery after losing his arm in a freak accident in February 2014

O'Brien: Most important thing is that you gain strength by admitting you need help

Winston Churchill once said, “If you’re going through hell, keep going.” That quote has always resonated with me, but never more so than during this past year. Since I lost my arm in a freak accident in February 2014, I have tried mightily to put those words into action, constantly focusing on forward motion.

Even though this is the story of my life in many respects, I was not particularly interested in telling it – or having it told. To do so would be tantamount to dwelling on a loss instead of taking stock of what I have. I would be moving in the wrong direction.

So when my friend and former colleague Sanjay Gupta asked if I would agree to cooperate on a story looking back over the past year, I was very reluctant. But Dr. Gupta can be very persuasive and convinced me it was important because it might, in some way, educate others. I took the bait, and then the interview evolved into a one-hour film.

“A Life Lost and Found” is a very powerful film. I would be moved to tears watching it even if wasn’t my own story, writ large. It was also harder to watch than I anticipated, which may seem hypocritical given my career of asking people all kinds of personal questions that intrude on their private lives. Turnabout is fair play, right?

Forgetting

The human mind is good at rewriting history. As Barbra Streisand crooned, “What’s too painful to remember, we simply choose to forget.” Our ability to suppress painful memories is a tremendous coping mechanism; it allows many of us to survive our daily lives, to carry on after loss and to pursue our dreams. But at what point does a healthy ability to forget become an unhealthy form of denial?

It’s a question I ponder frequently. Over the past year, I’ve learned that people are not bashful about telling me how to cope with my loss. Some suggest I haven’t taken the requisite interval to stop, reflect and work through the so-called stages of grief.

They imply I am in denial, but I am not sure I know the difference between denial and survival. I do know there is no manual for how to grieve. We all must find our own way through life, and frankly, we are all largely defined by how we cope with loss.

When I woke up from the surgery one year ago, I thought my arm was still there. It was a phantom that I still feel today. Once I realized my plight, it was hard to keep my thoughts straight. So many questions about the future all at once.

Could I be the father, provider and friend that I used to be?

Could I tie my shoes and butter my toast?

The things worth living for

The more I thought about these questions, the darker my prospects seemed. It would have been very easy at that point to surrender to it all. But then I thought about my kids and my friends and my career, and I realized I wasn’t ready to raise the white flag. Not by a long shot. For me, the best thing to do was get back to work. And diving in helped me get through the darkness and made me realize it wasn’t time to put a fork in me yet. I love my family. I love my friends. I love what I do. It is all worth living for no matter how many limbs I have.

Perhaps the most important thing I have learned since my accident (besides how to drive with my knees so that I can simultaneously drink my grande latte) is that you gain strength by admitting you need help.

At first, this seemed counterintuitive. I never did because I was convinced the opposite was true: that reaching out was an admission of weakness and a surrender of my self-worth.

Along with those who think I should take time off to “recover,” there have been many others who have encouraged me to fly – literally and figuratively. I have tapped into a rich vein of help, sometimes solicited, sometimes out of the wild blue Internet, that has reinforced and enabled my desire to push the one-armed envelope.

College students make robotic arms for children without real ones

The professionals at the National Rehabilitation Hospital in Washington were at the pointy end of the spear in my battle to get my life back. Even though I threw all kinds of curve balls in their direction. One day, I walked in with cameras, lenses, batteries, tripods, monopods, harnesses, and announced to my occupational therapists that my first “mono-mano” assignment in the field was going to be to travel to the Arctic, complete with four days in a tent camping on the Denali ice sheet. They would have been forgiven if they replied with gales of laughter and an emergency consult with a shrink.

Instead, they embraced the challenge and shifted into problem-solving mode. Later, when I told them I wanted to ride my bicycle 300 miles across Michigan over two days, even though I was unable to ride a two-wheeler safely anymore, they again, said, “No problem.” My prosthetist gave up a weekend to craft an arm that got me back on my bike, and got me through the ride.

These days he and I have been talking about the best strategy to get me back in the cockpit of an airplane. I’ve flown a handful (if you will) of times and I’m certain it will just be a matter of time before the Federal Aviation Administration will give me its imprimatur to return as a private pilot.

The truth is, I have learned my challenge is really not much more than an inconvenience. When I go to therapy and see what others are overcoming, I don’t think much about what I have lost, but rather what I still have and what I have gained. I am a better person than I was before because I have learned to receive love, care and help.

I am proof that life can change in an instant. And nobody really knows how he or she would handle something like this, and nobody can tell another person how best to walk through hell.

I don’t think you need to be superhuman to bounce back from these things. I believe it is something we all have inside of us. The question is whether we want to access it.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.