Story highlights

Social media project relives run up to Russian revolution of 1917

Styled to emulate Facebook, a timeline reveals months leading up to Bolshevik Revolution

What was life like for Russians such as Tsar Nicholas II and Vladimir Lenin in the months leading up to “the most tragic moment” of that nation’s history: the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917?

Mikhail Zygar, a journalist from Russia has launched an ambitious social media project with the aim of answering that very question.

He set up a networking website titled 1917: Free History which is similar to Facebook with the ‘friends’ based on the real-life heroes and villains of the revolution.

On a timeline, the characters are posting messages, pictures and even videos in a mock-contemporaneous account of events during the weeks and months leading up to it – all based on historical evidence.

“It creates an atmosphere of this day, but 100 years ago and it gives the possibility to look at it from the inside and to learn first-hand, just what those characters were thinking, what are they afraid, or reaming of,”’ Zygar told CNN.

Among them are household names: Vladimir Lenin, Tsar Nicholas II and Joseph Stalin.

Bringing history to life

In 1917, two revolutions overthrew the imperial government, bringing Bolshevik troops to power. Facing riots and revolt, Tsar Nicolas II abdicated his throne and along with his family, the last tsar of Russia was brutally executed the following year.

Lenin and Stalin were leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution, forming a provisional government that would later become the USSR.

Other prominent names from early 20th century Russia feature on the site including the artist Kazimir Malevich, the author Vladimir Nabokov and ballerina Anna Pavlova.

Russians are not the only nationality to feature – Rudyard Kipling, Pablo Picasso and George V all play a prominent role too.

Each character has his or her own page and all of the information has been compiled from letters, memoirs, diaries and other documents from the era.

Zygar explained: “There is no ability to skip days, events unfold in real time.”

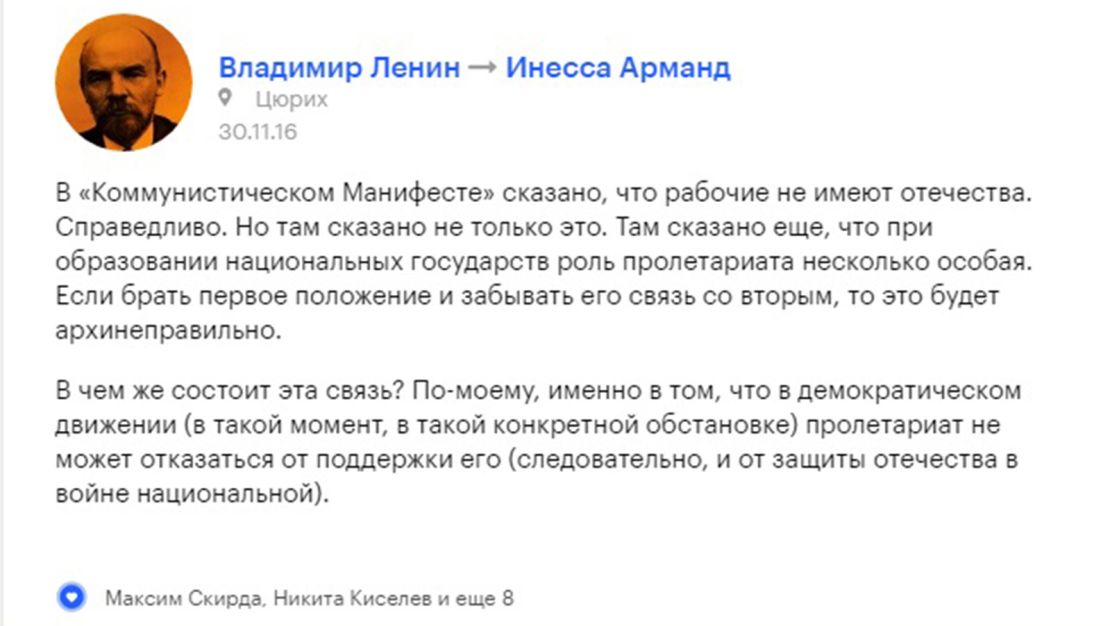

For example, on Thursday December 1, 1916 we find Lenin posting from Zurich in Switzerland where he was still in exile at that time. The post shows him discussing the Communist Manifesto.

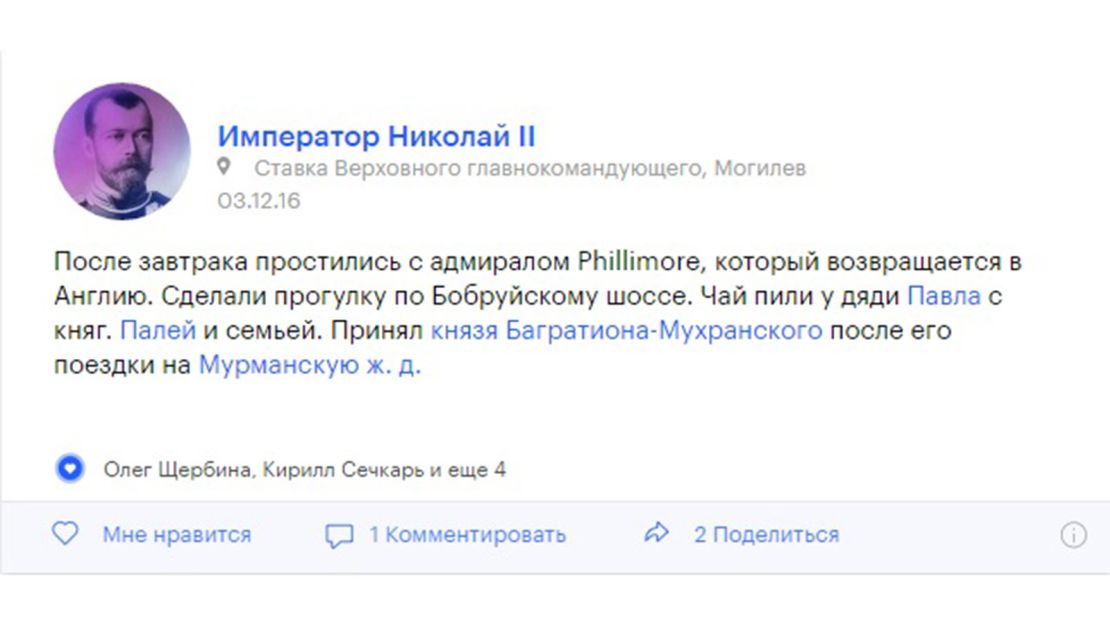

Meanwhile Tsar Nicholas II is also posting messages. He appears to be far from worried about an impending revolution, instead posting about his daily routine.

On December 3, 1916 he “writes” about his breakfast, a farewell to an English Admiral and taking a family member to a train station.

When history and art collide

Zygar, the former editor-in-chief of TV Rain, Russia’s only independent television channel, explained that the purpose of the project was to “use social media not as service but as a generator of art. To revolutionize the way of learning and teaching history.”

But the project was not created for schools. Instead Zygar describes it as “educa-ment” – a mix of education and entertainment, aimed at a much broader audience.

“You can watch it as a TV show, day by day, waiting for something new and interesting to happen to your new friends.”

When asked if he felt there would be an element of nostalgia from people, he said: “It’s obviously not about nostalgia because no one is feeling nostalgic about what happened 100 years ago. 1917 is the highest peak of Russian culture and civil society. It is the best and most tragic moment of Russian history.”

Zygar adds: “The project does not have any other motive but “it’s for the audience to decide what conclusion they are going to make. Do they think the middle class of 1917 resembled middle class of 2017?”

An English version of the site will due to be launched in early next year and run through until January 18 2018 – the date the new government formed a century earlier and, as Zygar calls it, “the day of the death of Russian democracy.”