Are you experiencing the following symptoms?

Insomnia: No sleep because you dread what happens over the next four years.

Hallucinations: You keep thinking that what you saw on TV last November must be a bad dream.

Fits of rage: You’ve unfriended half of your Facebook friends and you won’t talk to certain relatives about politics anymore.

If so, you may be suffering from a “Trump Slump.”

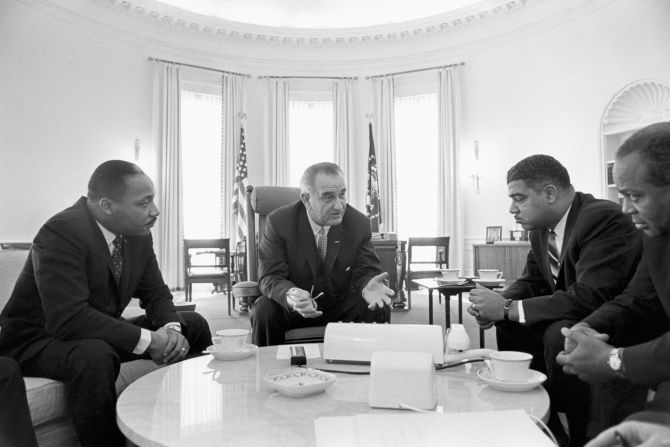

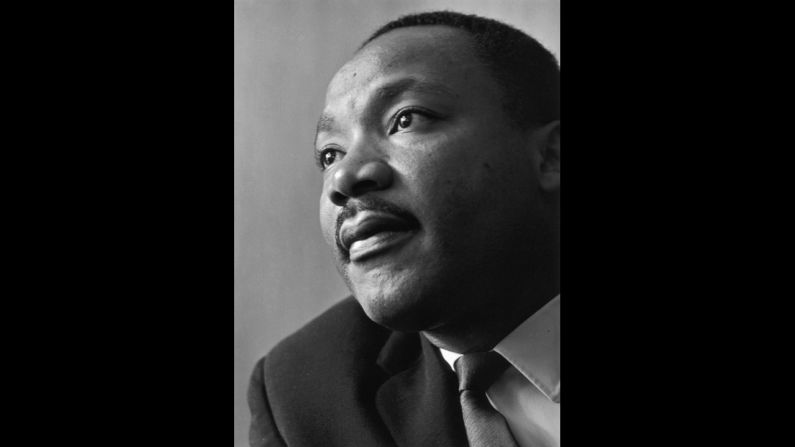

There are millions of Americans who are feeling just fine. For them, Donald Trump is a champion, a truth-teller who takes on the elites and will restore America’s greatness. But there are other Americans who have been mired in a stupor since election night. If President Barack Obama seemed to them like the fulfillment of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, then Trump represents their nightmare.

Both King and Trump will compete for headlines this week. On Monday, King will be celebrated. On Friday, Trump will be inaugurated. CNN asked a group of activists, historians and King biographers to elaborate on this coincidence by answering one question: What can Americans bracing for the Trump era learn from the life of King?

They cited three key moments from King’s life: a conversation he had with an enemy; a disaster that followed one of his greatest triumphs; and the subversive nature of his best-known speech. One even came up with a surprising message for those who label all Trump voters stone-cold racists: You’re dishonoring the spirit of King.

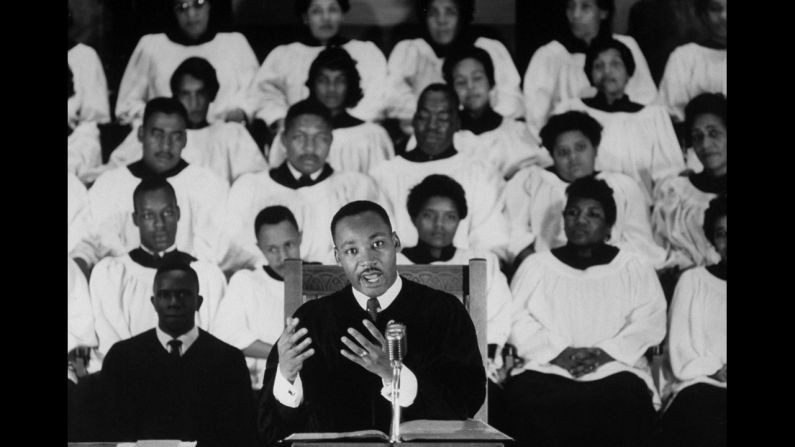

No. 1: How King died for poor white people

King was in a Birmingham jail in 1963 when he developed an odd ritual with his white jailers. They would come by his cell to tell him why segregation was right and intermarriage wrong. A polite debate would ensue. The white jailers would return the next day for more.

One day, King asked one of the jailers how much he made. The jailer told him. King recalled what happened next in one of his most famous sermons, “The Drum Major Instinct.”

“I said ‘Now you know what? You ought to be marching with us,’ ” King recalled. “‘You’re just as poor as Negroes. … You fail to see that the same forces that oppress Negroes in American society oppress poor white people.”

After Trump’s stunning victory, some people opposed to his candidacy vowed not to call him their president. Some cut off relationships with Trump supporters or called them all racists.

It was a new form of segregation: I shall only associate with those who share my political beliefs.

That kind of decision wouldn’t fly with King. He didn’t withdraw from his white jailers or lash out at them. It was a pattern that ran throughout his life, says David Garrow, author of “Bearing the Cross,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of King.

“King consistently distinguished between the evil deed and evil doer. He never hated anyone,” Garrow says.

“I see all these progressives filled with this hatred and loathing of Trump voters, but we never see King talk in hateful or loathing terms about Bull Connor or Jim Clark,” Garrow says, referring to two notoriously racist Southern white sheriffs.

“So much of the liberal left today is allowing themselves to be subsumed with a hate and anger that is utterly contradictory to King’s spirit.”

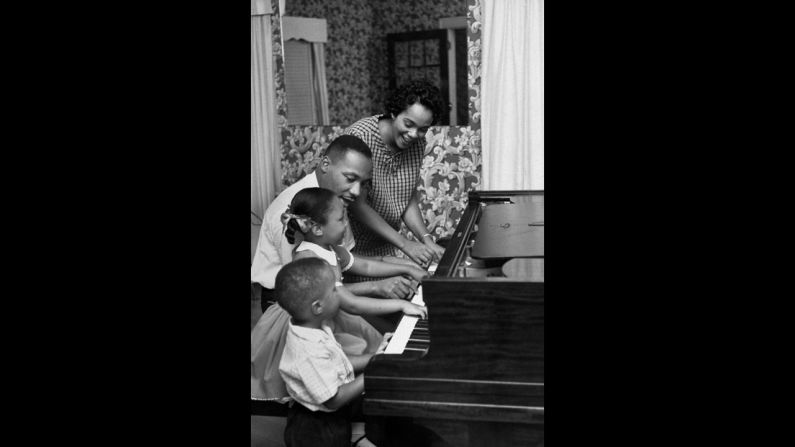

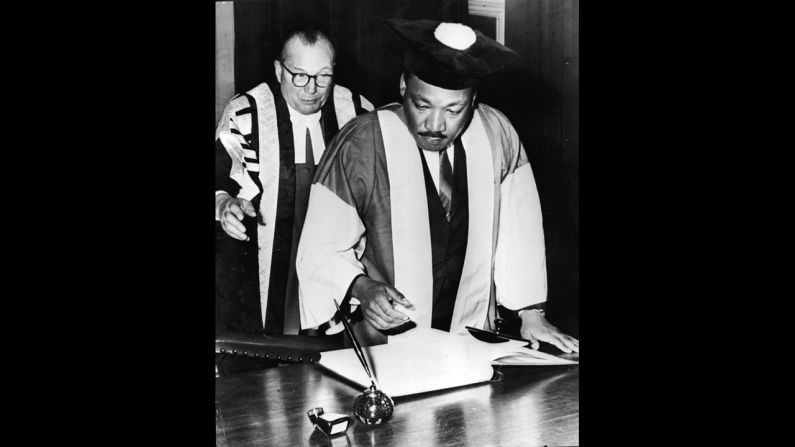

King’s refusal to demonize others extended to his organizing tactics. He’s often depicted as a black civil rights leader. But that’s not accurate. He was a human rights leader. He constantly sought to expand his civil rights coalition. He built ties with rabbis, white union leaders and black gang members, even traveling to India and Africa to forge relationships.

One of King’s most courageous public stands came in the defense not of black people but of Asians.

On April 4, 1967, he delivered a famous speech denouncing the Vietnam War in which he talked powerfully about the suffering of the Vietnamese people. He had been moved to give the speech after seeing pictures in a magazine of North Vietnamese children burned by napalm bombs dropped by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. He was roundly denounced by the media and even black leaders. Funding for the civil rights movement dried up, and President Lyndon Johnson stopped talking to him. But he never abandoned his anti-war position.

“He had a genuine spiritual core in which all souls were the same,” says John Baick, a historian who teaches at Western New England University in Massachusetts.

That included poor, working-class white people.

There’s a lot of talk today about the white, working-class voters who helped put Trump in office. Some say Democrats ignored and belittled them. No one could have made that charge against King.

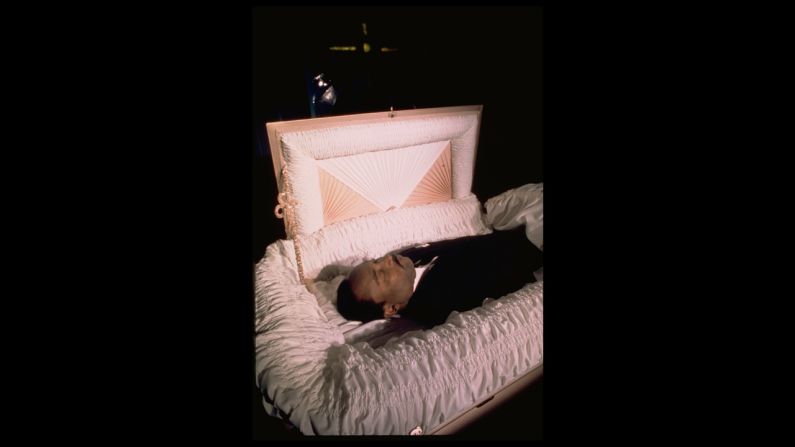

He died while trying to help poor white people.

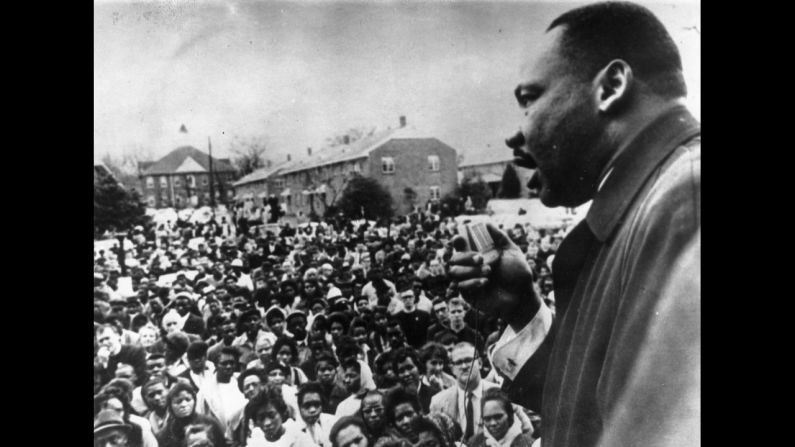

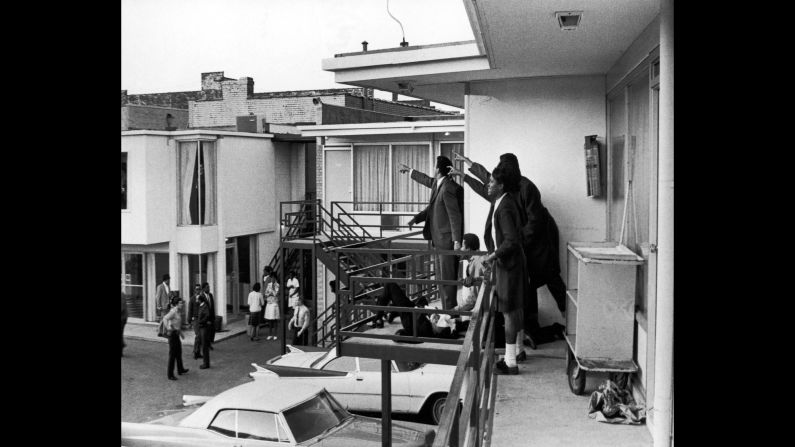

When he was assassinated in 1968 he was about to launch his most audacious movement – the Poor People’s Campaign. He had recruited an interracial army of poor people – white Appalachians, Latinos, Native Americans and blacks – to descend on Washington and shut it down if necessary to force the federal government to address poverty. It was Occupy Washington 40 years before there was an Occupy Wall Street.

In a 1964 Playboy interview, King specifically mentioned the plight of poor whites when he said the country needed a $50 billion federal program to address poverty.

“I do not intend that this program of economic aid should apply only to the Negro; it should benefit the disadvantaged of all races,” King said.

King’s refusal to just be a black leader was reflected in a quote he often used:

“We are tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality. And whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. …I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be.”

No. 2: King’s ‘tough faith’

Inspirational. Kind. A dreamer. Those are just some of the words people use to describe King. But here’s one you rarely hear:

Tough.

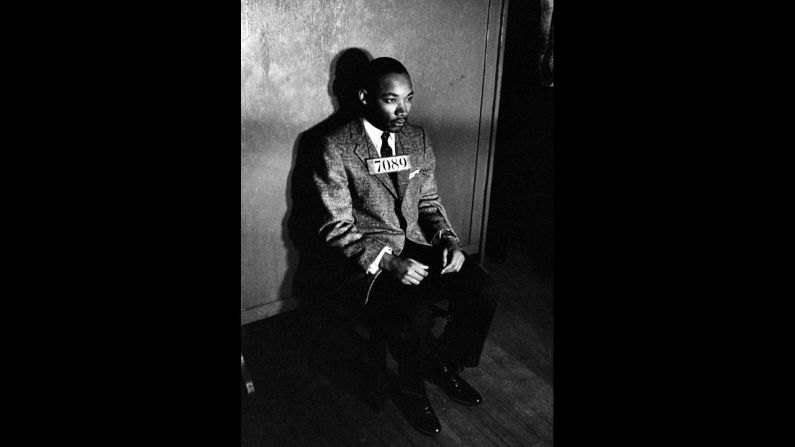

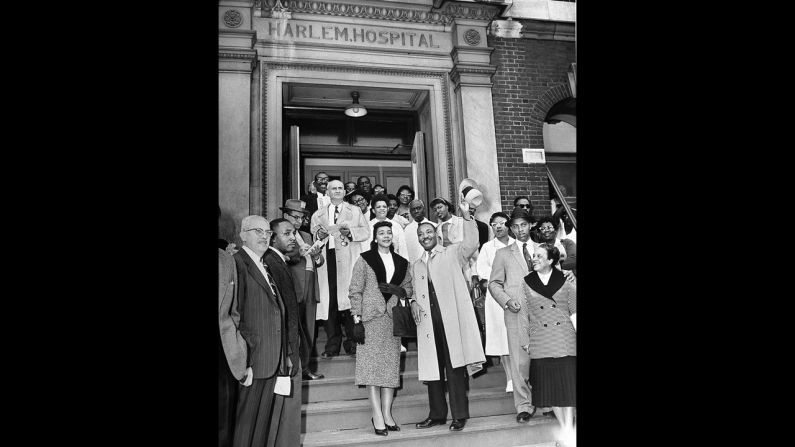

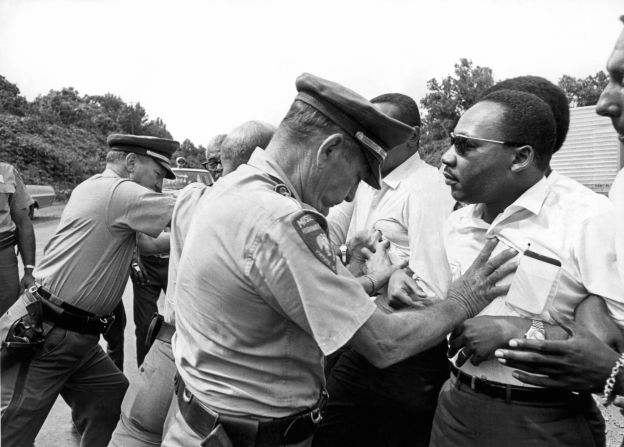

Don’t be fooled by the ministerial smile and deacon’s clothes King habitually wore. He was relentless. He was jailed 14 times, stabbed once in the chest, beaten at least twice in public. His home was bombed, he received constant death threats, and there’s evidence that suggests the FBI even tried to get him to commit suicide by threatening to send his wife audiotapes of his extramarital trysts.

Yet he never abandoned his activism. He often worked 20-hour days and gave up to 450 speeches a year. One of King’s most famous sermons was on toughness. In “A Tough Mind and a Tender Heart,” King preached about the value of blending love and toughness and not settling “for easy answers and half-baked solutions.”

After Obama gave his farewell address last week, many people wondered if all the hope of the Obama era was futile. Some sounded like people who had given up on politics.

Toughen up, says Jonathan Rieder, another King biographer, and look at what King and other foot soldiers of the movement endured. These were people who had survived the Great Depression and World War II, been beaten and called names; some even lost their lives. They knew social change was never easy.

“The movement was always spiraling down into disappointment and demoralization,” Rieder says. “But the movement had success because people had stamina and resilience.”

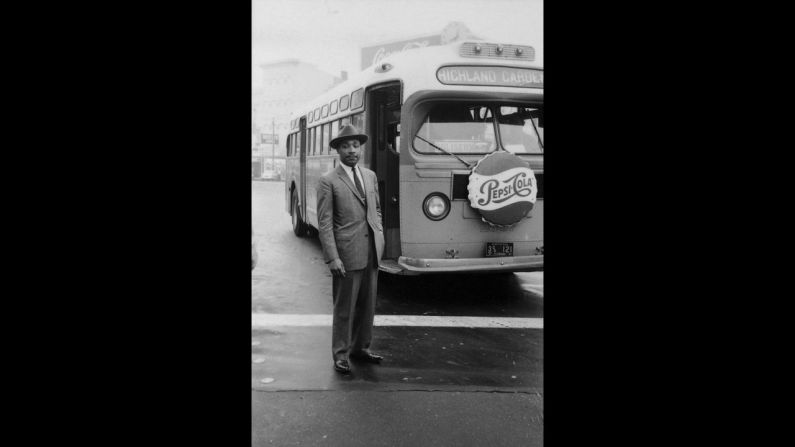

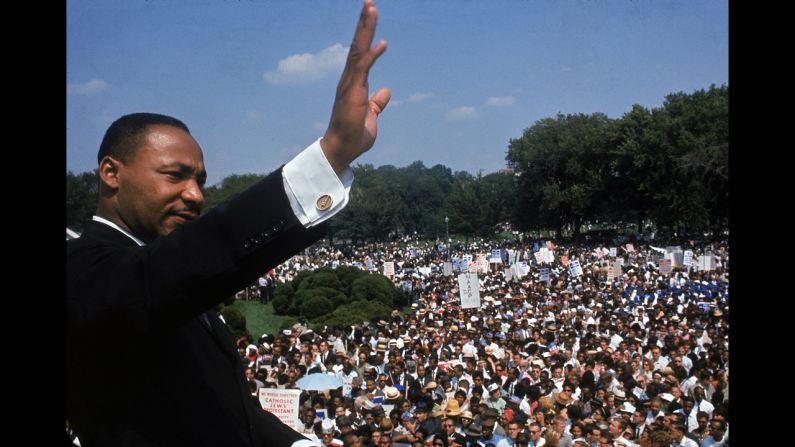

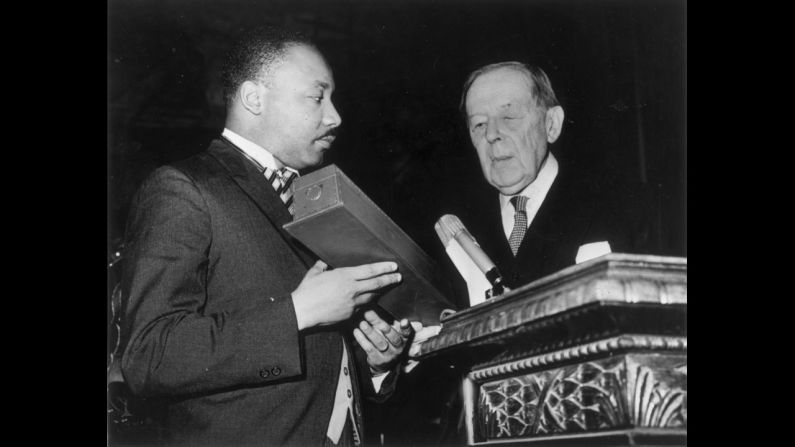

Consider what happened after King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on a humid, sunlit day in August 1963 in Washington.

Disaster after disaster followed. A civil rights bill that had been languishing in Congress couldn’t get a full vote; four black girls were murdered by a bomb blast in a Birmingham church as they prepared for Sunday school; President John F. Kennedy, who had given a courageous speech defending civil rights, was assassinated. All the momentum of the movement seemed lost.

“But we went back to work,” says the Rev. William Barber, a leader in “Moral Mondays,” the grassroots social justice movement formed in North Carolina in 2013 before spreading to other states. “We got the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed and the Voting Rights Act in 1965.”

Barber says he’s heard some people say Trump’s election is the worst thing in history.

“It’s a misreading of history,” he says. “It’s not worse than slavery, Jim Crow. It’s not the first time that America has elected a racist president in terms of policy. Trump’s election is as American as apple pie.”

People shouldn’t talk of Trump’s election as an extinction-level event, he says.

“We weren’t unelected; the Constitution wasn’t unelected; our faith wasn’t unelected,” Barber says.

Much of King’s toughness came from his faith, Rieder says. He drew from the faith of black Christianity, the faith formed by slaves. It was not a prosperity gospel. It was a faith that expected the faithful to suffer, knowing that good would eventually win. It was a faith built on sermons about resilience: Weeping may come at midnight but rejoicing comes in the morning; the resurrection follows the crucifixion; keep your eyes on the prize.

It was a tough faith that King leaned on when he became despondent, says Rieder, author of “The Word of the Lord is Upon Me: The Righteous Performance of Martin Luther King Jr.”

“They understood that Exodus wasn’t just a metaphor,” he says. “It repeats itself in every generation because there will always be people in bondage.”

No. 3: King the disrupter

Now is the time for healing. Now is the time to unite behind our new leader. Now is not the time to fan divisions.

Those are just some of the calls that greeted America after one of the most bitterly contested presidential elections in recent history. Those who say they will join “the resistance” to Trump are often derided as out-of-touch troublemakers.

So was King, some of his biographers say. They cite one of King’s most famous documents: “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.”

It reads today like something that would fit right in during the era of “Black Lives Matter.” It addresses the same tension: How to make noise to get justice.

Some of the lines from the letter are now classic. In one passage, King said the biggest threat to racial progress came not from vicious racists but from the white moderate who is “more devoted to order than justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

In others, King wrote that people had a duty to break unjust laws and that no demonstration ever came at the right time. And to critics who said his demonstrations incited violence, he asked: “Isn’t this like condemning the robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery?”

King had little sympathy for people who withdrew from political participation because they thought the system was too corrupt.

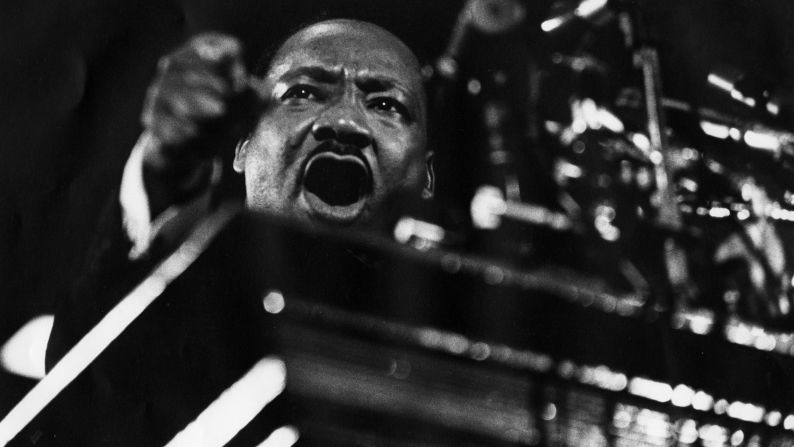

“We must learn that passively to accept an unjust system is to co-operate with that system, and hereby to become a participant in its evil.” Even in King’s biggest crossover moment, his “I Have a Dream” speech, he talked about the “marvelous militancy” of the movement, saying blacks “will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters.”

“He was a disrupter,” Rieder says. “He was a disrupter even in his most gentle speech.”

There may be more disruption ahead.

Barber says Moral Mondays is organizing a successor to the Poor People’s Campaign that will go to Washington. It’ll be another interracial army talking about poverty, health care, the environment.

Barber is not interested in merely remembering King – he wants to extend King’s vision. He is echoing a sentiment that made the social media rounds after Trump’s election: “Trump is the president; he’s not the future.”

“In every age, there had to be a group of people who understand that they were born for such a time as this,” Barber says. “King said he was tracked down by the zeitgeist.

“Now it’s our time.”