A new paper details how genetically modified pig hearts transplanted into baboons could support life and function for up to 195 days. The finding, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, takes scientists a small step closer to the possibility of using donor animal organs for human patients in need of a heart transplant.

“Consistent life-supporting function of xenografted hearts for up to 195 days is a milestone on the way to clinical cardiac xenotransplantation,” the researchers wrote.

“Despite 25 years of extensive research, the maximum survival of a baboon after heart replacement with a porcine xenograft was only 57 days and this was achieved, to our knowledge, only once.”

Xenotransplantation refers to the process of transplanting organs or tissues between different species. The new study included only animals, and much more research needs to be done before the approach of using genetically modified pig hearts for human organ transplants could be explored.

“Although the potential benefits are considerable, the use of xenotransplantation raises concerns regarding the potential infection of recipients with both recognized and unrecognized infectious agents and the possible subsequent transmission to their close contacts and into the general human population,” the US Food and Drug Administration says.

“Of public health concern is the potential for cross-species infection by retroviruses, which may be latent and lead to disease years after infection. Moreover, new infectious agents may not be readily identifiable with current techniques,” according to the FDA.

A heart transplant involves removing a damaged or diseased heart and replacing it with a healthy one from a donor who has died. The procedure is the only option for people with heart failure after all other treatments, such as medications or devices, have failed.

Yet when the supply of human donor organs falls short of the clinical need for organs, patients are often left waiting.

As of August 2017, the most recent data available, there were more than 114,000 men, women, and children in need of donor organs on the US transplant waiting list – and 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant, according to the US Government Information on Organ Donation and Transplantation.

Donor animal tissue has been used to build heart valves when a human’s valve must be replaced. These types of valves can be made of cow or pig tissue that’s strong and flexible.

A pig’s heart beats in a baboon

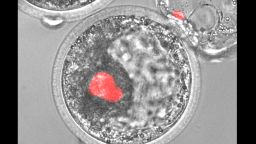

The new study, carried out between February 2015 and August 2018, involved transplanting hearts from 14 juvenile pigs into 14 male baboons. The hearts were genetically modified to express a human gene called CD46 and thrombomodulin, a membrane protein.

The researchers separated the baboons into three groups and performed the heart transplantation procedure in each group using various approaches.

In the first group, the hearts were kept in plastic bags filled with ice-cold solution and surrounded by ice cubes between their removal and when they were implanted. The results “were disappointing,” the researchers wrote. The animals, five total, survived for up to 30 days.

In the second group, the hearts were preserved with a solution containing nutrition, hormones and a type of blood cells called erythrocytes.

All four baboons in the second group showed better heart function than those in the first group, and they survived for up to 40 days.

In the third group, five baboons received antihypertensive treatment – because pigs have a lower systolic blood pressure than baboons – and additional medication was used to counteract cardiac overgrowth, in which a transplanted heart experiences greater weight gain than non-transplanted hearts.

After four weeks, all five baboons had good heart function, the researchers found, and two of them lived in good health for three months. The researchers decided to extend the study and found that the last two recipients in the group survived in good general condition for 195 and 182 days, respectively.

‘Perhaps the pig-pen is mightier than the sword?’

Limitations of the new study include that it remains unclear whether the approach could work in humans, but the findings take the scientific community one step closer to exploring the idea of transplantation in humans.

“The ability to keep a pig heart alive in a baboon for 195 days suggests that similar results could be obtained in human patients,” said Dr. Charles Murry, a cardiovascular pathologist and director of the Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

“I don’t think we’re ready for this step just yet, neither scientifically nor societally. Scientifically, we need to learn more about the long-term immune response to the foreign organ and whether there is evidence for viruses or other disease agents being transmitted,” Murry said.

“Societally, I think we need to let the public get their minds around this concept a bit and discuss it in coffee shops or wherever else civil discourse can take place. Perhaps the pig-pen is mightier than the sword?” he said. “Speculatively, I could imagine a first-in-human trial being a bridge to transplantation, in a patient whose heart is acutely failing and no donor organ is available. This might get them through the waiting period until a donor heart can be transplanted.”

But the study has provided two technical advances in science, Murry said.

“The first was in organ preservation. The authors pumped a blood-like solution, containing red blood cells, through the circulation to keep the tissue oxygenated and remove metabolic waste. This gave them much better short-term cardiac function,” he said. “Then, they dealt with the ongoing growth of the pig heart by slowing down protein synthesis, and this allowed them to go out to the planned endpoint of 195 days.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

The idea to use animal organs for transplantation has been discussed for decades but has never become a reality because the human body aggressively rejects animal organ transplants due to multiple and strong immune reactions, Barry Fuller, a professor in surgical science and low temperature medicine at the University College London, said in a written statement released by the Science Media Centre.

“Scientists have developed genetically modified pigs which could in theory reduce this strong immune response, but even then, significant problems have remained,” Fuller said.

Yet the study has shown that by using a new drug regimen and a new way of preserving the donor pig heart, “pig hearts survived for more than six months after transplantation into non-human primates (another version of xenotransplantation),” he said in part. “This new research can thus help both to bring organ xenotransplantation a step closer to human application, and to improve organ preservation techniques for human heart transplantation.”