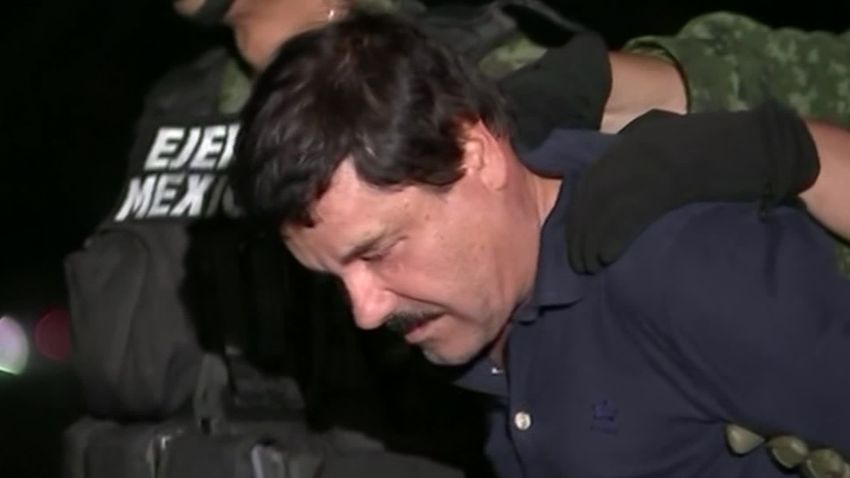

Jurors weighing the fate of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán have spent about 24 hours over a single week behind closed doors, sifting through testimony and evidence that could send the accused drug lord to prison for life.

The deliberations already have gone on far longer than many expected, given Guzmán’s infamous reputation as the alleged mastermind of a Mexican drug cartel that raked in billions in profits across a continent.

Some say the length of jury sessions, over four days so far, makes acquittal look more and more likely for Guzmán, 61, on any of 10 federal counts. They’re due to restart Monday.

But drawn-out deliberations may also just reflect the complicated nature of the federal case, including about 200 hours of testimony since mid-November, boxes upon boxes of physical evidence and 60 pages of jury instructions.

“They heard a lot of witnesses, they heard a lot of evidence. I would be a little more concerned if after a day or two they came back with a verdict,” said Jimmy Gurulé, a former federal prosecutor who has tried several cases involving cartel members and kingpin defendants.

Jurors could, too, be waffling over the credibility of key government witnesses, including some who admitted to heinous crimes and whose sentences could be reduced, per prosecutors, in return for the testimony, said Michael Lambert, an attorney on Guzmán’s defense team.

“If the case were as simple as the government argued,” he said, “the jury would be done by now.”

On a related score, the case’s dangerous stakes may also be weighing on jurors – and dragging out their debates.

For their own safety, jurors have remained anonymous and partially sequestered throughout the trial, and some have admitted they’re scared to face the alleged former head of a Mexican drug cartel. That fear, though unlikely to drive their decisions, could compel jurors to take extra time, said Sonia Chopra, a psychologist who consults attorneys on jury selection.

“The truth is, once these jurors are released, they’re going home.” she said. “They’re not going to have a security detail for the rest of their lives.”

‘Complicated’ case may be ‘counterproductive’

Twelve jurors – eight women and four men – are escorted to and from the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn by US marshals. A sworn court officer guards the door of the room where they work. Lunch gets delivered. In a separate room, six alternate jurors who also sat through the entire trial wait in case a juror must be replaced.

The jurors work off an eight-page verdict form that includes 10 criminal counts of which Guzmán stands accused, including engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, drug trafficking, and firearms and money laundering conspiracy charges.

The packet, Gurulé said, is longer than normal. It took US District Judge Brian Cogan several hours on Monday to deliver the jury instructions. That, in itself, could be stretching out jury discussions, the former prosecutor said.

“It’s unusual, it’s complicated, it’s confusing and it’s counterproductive,” Gurulé said. “The jury’s going to be struggling with connecting the dots, cross-referencing evidence with this.”

Already, jurors have sent Cogan several notes, most asking for what amounts to hundreds of pages of testimony from government witnesses.

“You’ve asked for the whole testimonies. So, that’s going to take a while,” Cogan said Wednesday, eliciting a laugh from some jurors.

Thick binders of testimony transcripts sat Thursday on tables in the courtroom as attorneys on both sides considered another request from jurors for excerpts of testimony.

The instinct to review the material may show jurors simply are doing their due diligence, Gurulé said.

“They’ve heard from so many witnesses, their memory has probably faded. They’re probably having some disagreements,” he said. “In order to resolve the confusion, they say, ‘Let’s just get a copy of the transcript.’”

Or, he said, it could suggest prosecutors “overtried” the case by offering jurors too much information and giving them too many charges to consider.

“You don’t have to throw in everything including the kitchen sink. You gotta prioritize the criminal acts,” Gurulé said. “They’ve gotta present a more compact case.”

‘They need a break’

The case’s darker elements also may be stretching the jury thin, prolonging the time needed to reach consensus. Prosecutors called witnesses who admitted they’d taken part in murders, trafficked drugs and bribed public officials.

“The government’s case is based on the testimony of mercenaries, who traded their testimonies for leniency,” Lambert, the Guzmán team lawyer, said. “The jury clearly saw through that and are taking this responsibility seriously.”

Jurors also heard gruesome testimony that one expert said could trigger symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder, Chopra said.

The length of the trial – and jurors’ orders not to talk with anyone about it – could be one of the biggest factors triggering stress, she said.

“A great buffer for stress is social support, and jurors don’t have that,” Chopra said. “You can’t go home and talk about it. It has to have an effect on your relationships with your family and your social networks.”

Each day during the first week of deliberations, jurors sent Cogan a note asking to leave at 4:15 p.m., though he’d offered to let them meet late into the night. They also declined to work on Friday.

Both decisions could delay verdicts. But they also give jurors time to decompress and a way to exert control over lives consumed for months by one of the most high-profile criminal trials in recent memory, Chopra said.

“This has been all-consuming for them for months at a time,” she said. “They need a break. They want to be able to carve out some time for their everyday lives.”